My reading list for this “Hymns in American History” project—for want of a title—is expanding in interesting directions. As I add books to my list I am continually reminded of the challenges posed by working on a project in that particular corner of our broad tent where “Intellectual History” and “Cultural History” and “Black History” and “Religious History” and “Literary History” overlap.

I think that’s called “American Studies,” but I can’t be sure.

In any case, what I’m finding—and I’m a novice reader in this area of scholarship—is that hymnology as a broad field does not overlap with American studies, never mind American intellectual history, as much as it could. And, of course, vice versa—hence the need for our project.

I do not have library access to some of the key journals of hymnology (you can find those listed in a helpful guide at the University of Illinois Library), the most important of which would be The Hymn. So I can’t speak to the interdisciplinarity that may manifest itself within that journal.

I can say that books on the history of hymnody in the US tend to focus on white Protestant traditions, tend to privilege evangelical hymnody among those traditions, and tend to be written with an eye to the internal significance of hymns for particular groups of Americans. There are probably some good historical reasons that studies of hymnody before the 20th century don’t have much to say about, say, the role of congregational singing in the Catholic church (not usually part of the service, particularly in the vernacular, until after Vatican II; dearth of archival records for some immigrant groups/communities). But a lot of this scholarship comes out of seminaries, schools of music, or Christian colleges and universities, some with denominational affiliations.

Denominational demarcations naturalize a focus on the history of Baptist hymnody or the history of Methodist hymns or the history of Lutheran hymns in German and English in the US. Particular hymnals also structure the field, from the Bay Psalm Book to The Sacred Harp to Hymns for Worship, and key publishers or publishing houses (some officially affiliated with particular denominations), make it possible to trace the shifting repertoire (scholars call it repertory, but that reminds me of my beginning piano books, and I cannot) of the Methodist Church or the African Methodist Episcopal Church or (heaven help) the Episcopal Church.

(True story: I was talking with the Episcopal Bishop of the Diocese of Dallas earlier this year. He asked me what I thought was the greatest gift that ex-Evangelicals could bring to the Episcopal church. Without pausing for a fraction of a second, I said, “Better hymns with a melody line that makes sense.” That wasn’t the answer he was looking for, but at least he laughed. He said, “What else?” and, again, no filter, I said, “A more spontaneous style of preaching.” He found that slightly less amusing. The answer he was looking for was, of course, a heart for evangelism. I said, “Why do you think I bailed on the Baptist church in the first place?” And that’s the story of how L.D. Burnett is no longer discerning a call to the Diaconate.)

Speaking of Evangelicals, a leading Evangelical scholar of Pentecostal and gospel church movements, Edith Blumhofer, worked out of Wheaton

. She wrote what remains the only scholarly biography of Fanny J. Crosby, the most prolific and most famous gospel/revivalist hymnwriter of the Gilded Age / Progressive Era (Her Heart Can See: The Life and Hymns of Fanny J. Crosby, 2005). “Blessed Assurance,” “Rescue the Perishing,” “I Shall Know Him,” and literally more than a thousand other songs came from her pen, some published under pseudonyms so that people would not begin to notice that Crosby was taking up a fair amount of space in the songbook.

Blumhofer co-edited a few volumes on hymns, including one with Mark Noll (Sing Them Over Again to Me: Hymns and Hymnbooks in America, 2006) and a more ecumenically-oriented essay collection (Music in the American Religious Experience, 2006) with Philip Bohlman and Maria M. Chow.

These co-edited volumes and others are a godsend to me precisely because I don’t have access to the leading journals in the field. And they show the promise of an interdisciplinary approach to the presence of hymns in American history, though most scholars focus on hymns within a faith tradition, rather than hymns as reflections of or influences upon broader currents of American thought far beyond the church-house doors. But there are some notable exceptions, including essays in Sing Them Over Again to Me by Heather D. Curtis (“Children of the Heavenly King: Hymns in the Religious and Social Experience of Children”) and Susan VanZanten Gallagher (“Domesticity in American Hymns, 1820-1870).

Jon Mitchell Spencer’s monograph, Black Hymnody: A Hymnological History of the African-American Church is absolutely indispensable, and I would give anything to be able to search the Social Science Research Index to find more recent articles and monographs that cite it. But even Spencer’s monograph is a story of institutional life, and what makes hymns so rich as a vein of thought to mine is precisely how they travel between and beyond institutions. A lot of ideas can hitch a ride on a singable tune.

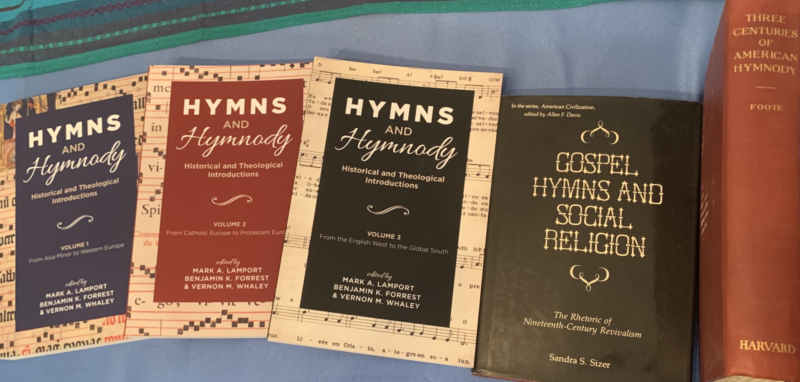

I did manage to acquire a recently-completed three-volume encyclopedia of hymnody whose final volume in particular will be useful for this project. That would be Hymns and Hymnody: Historical and Theological Introductions, Vol. 3, From the English West to the Global South. The whole set begins with songs of the first-century church and with contemporary worship styles (i.e., praise choruses repeating ad nauseum. Sorry, I want six verses of a hymn with four part harmony and at least one theological claim per verse). And contemporary worship is definitely a part of the story of hymnody lost and found in American life. The bibliographical references within this encyclopedia are going to be of great help with our project.

But oh, our project.

When it comes to a broad cultural/intellectual history of hymns in American life and thought, or American life and thought reflected through the prism of hymns, the prevalence of co-edited volumes speaks to the extraordinary challenge of offering a coherent or cohesive narrative on a topic so incredibly broad. If it were easy—perhaps, I should say, if it were possible—someone would have done it recently.

Could we with ink the ocean fill,

And were the skies of parchment made,

Were every stalk on earth a quill

And every man a scribe by trade… it still wouldn’t be possible.

For all that, David Mislin and I are going to give it a try. All bibliographic suggestions welcome.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

If you don’t already have it on your list, I’d recommend a look at Christopher Phillips, The Hymnal: A Reading History (JHU Press, 2018)