I’ve been thinking about cheese lately. For whatever reason, among my favorite memories of hanging out with my friend Bob over the years comes from the time we went to visit my significant other Kathy at her credit union workplace. Seeing her there is always great, because like any of us, the phenomenology of her office surroundings, that particular space, generates a certain formal way of being in the world, however hard any of us might try to believe it’s not that way by some conjuring after the fact. There’s an etiquette implied there. The “look” of Kathy in that space is “work Kathy,” which is not dissimilar from when I meet people in my office at work—“work Pete.” As we meet in that space, we measure up our bodies differently somehow, probably owing to how intentional offices can be. We designate this time/space for this activity or project. Obviously, with a pandemic raging, you eventually feel a terrible ache for differences like these. In so many lives right now, longing like this means everything.

On that occasion years ago, Bob and I both felt the formality, the unspoken “sense” of that kind of being-in-the-world with “work Kathy.” So we sat down in the chairs in front of her desk, an inevitable simulation of a couple applying for a loan or getting something sorted financially. There was a weird uneasiness, something akin to mild imposter syndrome I guess. (It reminds me of the time Bob and I shared an elevator at the AHA in the aughts as broke grad students. A couple of older men got on, only for Bob to remark, in full absurdist greenhorn wonder mode, “Man alive, Pete, did you see the pillows in these rooms? Never seen anything like it. Softest pillows in the world I reckon.”)

Without missing a beat on that day in the credit union, Bob took up the guise: “Can I get a loan for a piece of cheese? I mean, it’s a really big piece of cheese. I mean a big piece of cheese.”

To her credit, Kathy just went with it, asking more about the cheese, whether it was one of those huge wheels of cheese, what the terms of a cheese loan might be, because in some cases, those can get mighty expensive. I could be wrong, but I think I recall us looking up historically large cheese wheels when we got home that day. Something tells me Bob already knew about the “Mammoth Cheese” exhibited at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago because he knows lots of sublime, trivial information like that.[1]

I tend to notice cheese whenever it appears in film or fiction, specifically in cases of mistaken identity. In Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (1931), the Tramp is sometimes an agent of confusion because he orients himself differently in space and time owing to who he is, at the bottom rung of society, “lumpen,” moving between worlds. He gets bullied by newsboys (little jerks) at some moments while at others enjoys a role as boon companion to an alcoholic millionaire who cozies up to the Tramp only when blackout drunk at night. The millionaire doesn’t remember the Tramp at all by the light of day when he’s sober. As payback, the Tramp impersonates (sort of) the millionaire when he can, using the fat cat’s fancy car to woo a blind flower girl who assumes he’s someone he isn’t.

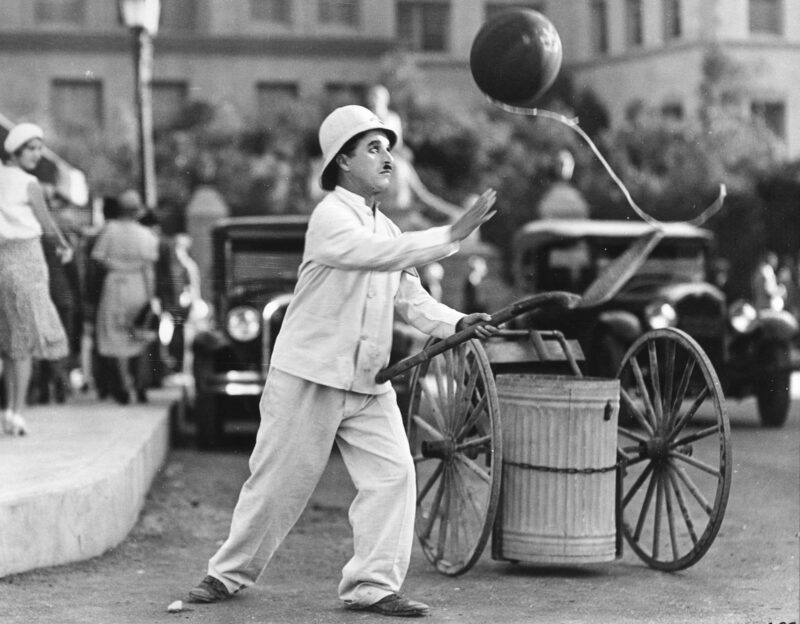

In love with the blind flower girl and desperate to gin up the cash to save her when she falls ill and faces eviction, the Tramp takes a job as one of Colonel Waring’s “White Wing” sanitation workers, pith helmet and all. There’s a neat gag where he cleans up horse manure only to have an elephant show up on the street: a merciless send-up of Sisyphean street labor and imagined empire, all implied by pith-helmeted sanitation workers shoveling shit. Waring apparently thought the uniforms would keep street cleaners out of taverns, sticking to the job on the streets. How’s that for a phenomenology of the workplace? “Work-Tramp.”

The Tramp as a “White Wing” in City Lights

After a morning of manure shoveling, the Tramp goes to lunch. On a barrel next to a sink, a fellow worker prepares himself a cheese and onion sandwich right next to a piece of soap (weird, sandwich, man). The Tramp, washing his face in the sink, reaches out blindly as the other worker looks away, picking up the wedge of cheese from the sandwich then in preparation instead of the soap. Recognizing that cheese makes bad soap once he tries to use it at the sink, the Tramp chucks said cheese to the ground, picks up the soap wedge from the barrel top, finishes his ablutions, and then places the soap squarely onto his co-worker’s open slice of bread. The worker eats a chunk of soap sandwich, spits it out, and then balls out the Tramp, only to have soap bubbles pop out of his mouth in the yelling. Of course, the Tramp plays with the bubbles in his typically whimsical way. Oooh, bubbles!

Cases of mistaken identity like this are more important than we tend to think. So are mammoth cheeses. A piece of cheese can feel like a piece of soap as we go about our business in the world, and vice versa. We move through the world in happy-go-lucky or unhappy-go-unlucky ways lots of the time (or happy-go-unlucky or unhappy-go-lucky). This means lots of what we experience immediately in our “present” appears to us as background, unformed, or like a blur, or off somewhere in the periphery waiting as the flow brings other things into focus, recognizing them fully only as we go about the measuring up, that gearing of our different senses into one another as our intentions shift from this to that project.

We anticipate the gags in City Lights from the privileged point of view provided spectators of the film. And Chaplin was of course unparalleled when it came to staging sleights of hand and body, subtly tweaking workings of power and its various etiquettes, such that one thing could be mistaken for another owing to the different wavelength or pulsing of space/time lived by the Tramp. That guy left wondrous little wreckages as he moved in the city, obeying the peculiarities of his being-in-the-world. The possibilities were endless.

I also recently watched the Jacques Tati film Playtime (1967). It’s really great. I can’t recommend it enough. I hadn’t seen it before this year. Playtime makes for a surprisingly life-affirming take on an imagined, hyperreal Paris, an impersonal Corbusierian nightmare of towers and glass chock-full of consumer objects American-style (Tati broke the bank making the set apparently). There isn’t much in the way of intentional dialogue. The plot is visual and aural. It features a Kafkaesque everyman hero named Hulot. Subtle gags of sight and sound come one after another in an atmospheric way at first. As I watched it early on, I thought about Josef K and the weird sense of guilt or even shame that comes along with modernity and its systems. Hulot tries to navigate the world and orient himself in it, but he mostly feels embarrassed in the trying. As in, “am I doing the right thing, here?” I found it laugh out loud funny. As he moves into ever more complicated scenarios, the action piles up, getting chaotic and ever more riotous. It turns out that more human beings taking up more space in larger numbers messes stuff up as they creatively adapt the spaces willy-nilly and against the etiquette of planning. (A running joke in a restaurant involves a clueless architect.) Watching it made me just ache with longing for public spaces.

But if you pay close attention, toward the end of the film Hulot mistakenly places a piece of cheese from one stand in a market onto to another with sponges atop it. It’s almost a throwaway little joke, or maybe not. I can’t be sure. Hulot mistakes seeing for the Tramp’s blind touching. In something of an homage (fromage? sorry) to “City Lights,” in the climactic moment in the film, the American woman Barbara admires a flower placed only secondarily in a gift given her by Hulot, and we the viewer see the wondrous replication of its form in a row of high modernist city lights running down the highway. One thing becomes another, and we see the whimsy in everyday objects anew, yet again.

[1] “Atlas Obscura” documents a simulacrum mammoth cheese: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/mammoth-cheese-replicas

0