Editor's Note

Today, as part of our #USIH2020 publications, we’re proud to share a paper by Jordan T. Watkins, assistant professor of church history at Brigham Young University. Check out our full conference program here, and register for tonight’s 7pm EST #USIH2020 panel, “Recovering the Centrality of Social Democracy in the Early Twentieth Century” here.

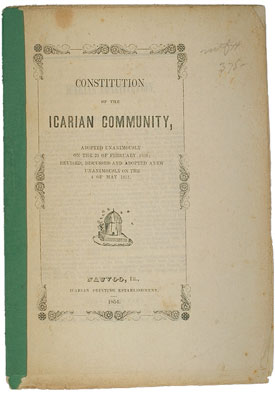

A major seat of American constitutional creation sits on the banks of the Mississippi River. In 1844 and again in 1850, two distinct groups set out to write a constitution in Nauvoo, Illinois. In March 1844, Joseph Smith and a number of his followers discussed creating a new legal creed. Six years later, after Nauvoo had been “abandoned by the Mormons,” Étienne Cabet and a group of Icarians arrived there from France and ratified their own constitution.[1] Both groups created a new government after facing persecution and in response to a social and moral order that had failed them. But whereas the Icarians created their new polity in the open, a small body of Mormons conducted their governmental deliberations in secret. While the Icarians made their constitution available for “any one” to read, the Mormons hid away the records of their constitutional meetings.[2] In fact, these records only came to light a few years ago, when the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints published them as part of the Joseph Smith Papers Project.[3] The differences between the Icarian and Mormon situations depended on a number of factors, including their distinct relationships to the American constitutional order.

A major seat of American constitutional creation sits on the banks of the Mississippi River. In 1844 and again in 1850, two distinct groups set out to write a constitution in Nauvoo, Illinois. In March 1844, Joseph Smith and a number of his followers discussed creating a new legal creed. Six years later, after Nauvoo had been “abandoned by the Mormons,” Étienne Cabet and a group of Icarians arrived there from France and ratified their own constitution.[1] Both groups created a new government after facing persecution and in response to a social and moral order that had failed them. But whereas the Icarians created their new polity in the open, a small body of Mormons conducted their governmental deliberations in secret. While the Icarians made their constitution available for “any one” to read, the Mormons hid away the records of their constitutional meetings.[2] In fact, these records only came to light a few years ago, when the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints published them as part of the Joseph Smith Papers Project.[3] The differences between the Icarian and Mormon situations depended on a number of factors, including their distinct relationships to the American constitutional order.

Debates over slavery contributed to the shape of that order. Most participants in those debates developed constitutional readings that supported their views, but some anti-slavery proponents appealed to higher law, and a few radical abolitionists, such as William Lloyd Garrison, damned the Constitution as a dead letter.[4] These options were not equally available to all. The power of Garrison’s stance depended on his firm place within the American republic. He could choose to dramatically “come out” from society in a way that black Americans such as Frederick Douglass could not. Seeking full admittance into that society, Douglass laid aside Garrisonian non-resistance and considered multiple means of abolition and equal rights, including political, constitutional, and violent avenues.[5] Meanwhile, John Brown, who uniquely pursued violent remedies, disregarded the federal Constitution and created a new one aimed at abolishing slavery and ensuring equal rights.[6] The slavery crisis shaped much of the era’s constitutional, anti-constitutional, and generative constitutional developments.

During the same period, some groups on the margins, including the Mormons and the Icarians, created constitutions to maintain and advance distinct cultural, social, economic, and religious visions. After facing persecution in France, Cabet and some of his followers journeyed to the United States, where they believed geographical and ideological space existed for them to develop a socialist republic.[7] While some American observers questioned their beliefs, many of their Illinois neighbors received them as “innocent and inoffensive strangers” from a nation with a republican legacy (“the land of Lafayette”) that intersected with their own.[8] Demonstrating a keen cultural awareness, Icarians used the language of New Testament Christianity and American republicanism and resolved “to submit, respectfully, to the laws of our adopted country.”[9] This band of 200-300 French emigrants, who professed a religion “devoid of all ceremony and superstitious practices” and mandated monogamous marriage, posed little threat to their neighbors, especially when compared to the thousands of Latter-day Saints who had inhabited Nauvoo.[10] While the Icarians’ written constitution created an alternative legal order, it also showed their embrace of Euro-American legal forms. In crafting a new constitution, they successfully navigated the currents of American federalism.[11]

In contrast, Mormon marginality emerged entirely within the American order, which both permitted and limited what Mormonism became. American pluralism left just enough space for the emergence of their unique beliefs and practices, from radical productions of new scripture to scandalous marriage arrangements. Such beliefs and practices, and the opposition they garnered, gave shape to Mormonism.[12] Mormons crafted their marginal status, then, though not entirely on their own terms. When their situation became precarious in Missouri during the 1830s and in Illinois during the 1840s, they sought relief and protection from within the American legal system. When that system failed to offer an answer to the Saints’ suffering, in large part due to a federalism nourished by proslavery ideology and politics, Mormons considered resolutions outside of the American legal system. In short, while the Icarians used American federalism to carve out space for a new constitutional order, Latter-day Saint frustrations with that federalism inspired an attempt to start the world anew.

In contrast, Mormon marginality emerged entirely within the American order, which both permitted and limited what Mormonism became. American pluralism left just enough space for the emergence of their unique beliefs and practices, from radical productions of new scripture to scandalous marriage arrangements. Such beliefs and practices, and the opposition they garnered, gave shape to Mormonism.[12] Mormons crafted their marginal status, then, though not entirely on their own terms. When their situation became precarious in Missouri during the 1830s and in Illinois during the 1840s, they sought relief and protection from within the American legal system. When that system failed to offer an answer to the Saints’ suffering, in large part due to a federalism nourished by proslavery ideology and politics, Mormons considered resolutions outside of the American legal system. In short, while the Icarians used American federalism to carve out space for a new constitutional order, Latter-day Saint frustrations with that federalism inspired an attempt to start the world anew.

Mormon constitutionalism emerged in response to religious persecution and in relationship to southern insecurities about slavery. In the early 1830s, a mob in Jackson County, Missouri, destroyed a Mormon press and tarred and feathered two Latter-day Saints, in part because of the Mormons’ supposed antislavery sentiment.[13] When Smith, who was in Ohio, learned of these developments, he wrote letters and dictated revelations that encouraged constitutional adherence.[14] These writings directed the Missouri Mormons to petition local and federal government for support. In one such petition, the Mormons introduced themselves as “citizens of the republic” and “members of the church of Christ,” and laid claim to the “rights, privileges, immunities and religion, according to the Constitution and laws of the State.”[15] Mormons thought of themselves as dual citizens; they belonged to the United States and to Christ’s church. The divine laws Smith revealed did not displace local or federal laws, though that remained a latent potential. When the Saints’ first petition failed to secure support, Smith encouraged Missouri members to continue to petition government even as he also promised that when “all Laws fail[ed]” them God “will not fail to exicute Judgment upon [their] enemies.”[16] In less than a week, Smith’s instruction gained the backing of a revelation, which urged the Mormons to “continue to importune for redress.” The same revelation indicated that the Lord himself had “established the constitution.”[17] During the 1830s and 1840s, politicians and commentators advanced the sacralization of the Constitution that had begun within a decade of ratification.[18] In Smith’s revelations, the Lord himself designated the Constitution as sacred.

And yet, the fact that Mormon sacralization rested on a revelation meant that believers ultimately valued Smith’s revelations over the framers’ Constitution. Indeed, the same revelation that sacralized the Constitution suggested its limitations. Comparing the Saints’ situation to the biblical parable of the relentless woman and unjust judge, the revelation instructed them to seek redress from the judge and “if he heed them not” to “impertune at the feet of the Govoner and if the Govoner heed them not” to “importune at the feet of the President.”[19] Anticipating government inaction, the revelation promised godly retribution: “and if the President heed them not then will the Lord arise and come forth out of his ?hiding? place & in his fury vex the nation.”[20] The logic of the revelation implied that the Saints should not allow inept government officials or even inspired writings obscure the ultimate source of inspiration and justice.

Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, the Saints continued to petition local and national government for redress and protection while awaiting divine retribution.[21] During the same period, their public stance on the issue of slavery shifted. While Mormons resided in the slave state of Missouri, they spoke against meddling with “bond-servants” and distanced themselves from abolitionists.[22] Once the main body of Saints found refuge in Illinois, they advanced antislavery positions.[23] In Nauvoo, they also worked to turn local politics in their favor and made expansive use of their chartered rights to protect Smith from enemies.[24] But broader American realities, including southern anxieties about federal intervention and Congress’s decision to table abolitionist petitions, enervated the Saints’ efforts to win federal redress.[25] As the issue of slavery gave shape to American federalism, that federalism contributed to Smith’s failed personal appeal to Martin Van Buren, the Saints’ doomed memorial to Congress, and Smith’s later inability to secure the support of prospective presidential candidates. The Saints viewed all of these developments as variables in an apocalyptic equation that hastened God’s justice.[26] The Saints persisted in pursuing means of redress, including through Smith’s own presidential campaign in 1844. However, while the Saints continued to exhaust all available means of redress from within the American legal system, they also looked beyond it.

The Saints’ failure to fully realize their rights as citizens of the republic pushed them to emphasize their ultimate allegiance to God. In that process, they embraced a unique version of Christian estrangement that, as Carrie Hyde notes, “offered moral vindication to oppressed groups, above and beyond the exclusionary practices of the state.”[27] The Mormon version prized divine reward and retribution but looked for fulfillment on earth as much as in heaven. In this way, Mormon estrangement tended to merge with a kind of Mormon nationalism.

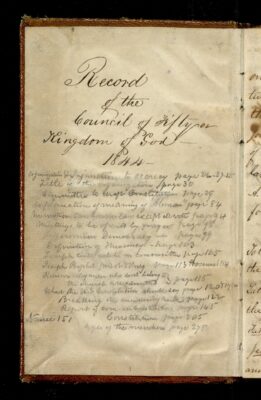

On 11 March 1844, Smith organized the Council of Fifty, envisioned as the governing body that would rule in the wake of God’s apocalyptic justice and the initiation of Christ’s millennial reign.[28] In the first meeting, the council discussed “forming a constitution … according to the mind of God.”[29] To that end, they appointed a committee to “draft a constitution which should be perfect, and embrace those principles which the [US] constitution … lacked.”[30]

Smith’s faith in government had long since expired and now his faith in the Constitution also waned. God had used wise men to craft that inspired document, but now God would use prophets to create a revealed legal creed. The fact that the Mormons’ constitutional reverence rested on a revelation implied that their ultimate faith in law and justice went beyond the document produced by inspiration to the source of inspiration itself. In other words, the Saints’ unique view of the Constitution’s sacredness freed them from viewing it as the final legal arbiter. Indeed, it allowed them to set it aside when it proved insufficient. If revelation could make the Constitution sacred, it could also make it obsolete.

The council still sought federal assistance and asserted constitutional allegiance. For example, on 26 March, they drafted a petition asking Congress to authorize Smith to “show his loyalty to … the constitution” by leading troops westward to spread American civilization.[31] The Saints’ unsettled status in society informed this ongoing petitioning. While Mormon marginalization was of a very different sort than that of black abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, Mormons could not afford to neglect political and constitutional appeals either.[32] But their marginalization also meant that when politics and the Constitution failed them, they were open to using other means, including an appeal to God and his immediate revelation.

[1] Étienne Cabet, History and Constitution of the Icarian Community, in The Iowa Journal of History and Politics 15 (1917): 224.

[2] Étienne Cabet, Colony or Republic of Icaria in the United States of America: Its History (Nauvoo, 1852), 17.

[3] Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, first volume of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016).

[4] Other abolitionists called for an amendment. Since the federal Constitution’s ratification, a group of Presbyterian Covenantors had criticized the framers’ sanction of slavery and their omission of Christ. See Joseph S. Moore, Founding Sins: How a Group of Antislavery Radicals Fought to Put Christ into the Constitution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[5] See T. Gregory Garvey, Creating the Culture of Reform in Antebellum America (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2006), 121-60.

[6] See “Appendix A: Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States,” in Robert L. Tsai, “John Brown’s Constitution,” Boston College Law Review 51, 1 (2010): 187-207. For analysis of Brown’s Constitution, see Tsai, America’s Forgotten Constitutions, 83-117; Tsai, “John Brown’s Constitution,” 151-186; and David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 250-54.

[7] See Cabet, History and Constitution of the Icarian Community, 214-32.

[8] Warsaw Signal, 7 April 1849.

[9] See, for example, Warsaw Signal, 25 August 1849. See also, Cabet, History and Constitution of the Icarian Community, 233-43.

[10] Cabet, History and Constitution of the Icarian Community, 233-43, quotation on 243.

[11] On the Icarian nation and constitution, see Robert L. Tsai, America’s Forgotten Constitutions: Defiant Visions of Power and Community (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 49-82.

[12] See R. Laurence Moore, Religious Outsiders and the Making of Americans (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 25-46.

[13] See John Whitmer to Joseph Smith, 29 July 1833, in Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, Brent M. Rogers, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds. Documents, Volume 3: February 1833–March 1834, vol. 3 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2014), 186-98. Jackson County citizens interpreted an article written by William W. Phelps as an invitation to “free Negroes and Mulattoes from other States to become Mormons and remove and settle among us.” John Whitmer to Joseph Smith, 29 July 1833, in JSP, D3:192. For the Phelps article, see “Free People of Color,” The Evening and Mormon Star, July 1833, 109. See also, “The Elders Stationed in Zion to the Churches Abroad,” The Evening and Morning Star, July 1833, 110-11. Phelps rejected these claims and insisted the Saints were “determined to obey the laws and constitutions.” The Evening and the Morning Star, Extra, 16 July 1833, [1].

[14] See Revelation, 6 August 1833, in Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, Brent M. Rogers, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds. Documents, Volume 3: February 1833-March 1834, vol. 3 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2014), 224; Joseph Smith to Church Leaders in Jackson County, Missouri, 18 August 1833, in JSP, D3:267.

[15] “To His Excellency, Daniel Dunklin,” Evening and Morning Star 2 (December 1833): 114-15. See also, William W. Phelps, et al., Clay Co., MO, to Daniel Dunklin, 6 Dec. 1833, copy, William W. Phelps, Collection of Missouri Documents, Church History Library (hereafter CHL).

[16] Joseph Smith to Edward Partridge, 10 December 1833, in JSP, D3:375-81

[17] Revelation, 16-17 December 1833, in JSP, D3:395.

[18] On the beginnings of this process, see Jonathan Gienapp, The Second Creation: Fixing the American Constitution in the Founding Era (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2018). I track the ongoing and increasing sacralization of the Constitution in Slavery and Sacred Texts: The Bible, the Constitution, and Historical Consciousness in Antebellum America (forthcoming, Cambridge University Press).

[19] See Luke 18:1-8.

[20] Revelation, 16-17 December 1833, in JSP, D3:396.

[21] See Edward Partridge et al., Petition to Andrew Jackson, 10 April 1834, William W. Phelps, Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL; William W. Phelps to Thomas H. Benton, 10 April 1834, William W. Phelps Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL; Petition to Daniel Dunklin, 10 September 1834, William W. Phelps Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL; see also, Appeal and Petition to Governor Dunklin, in John Whitmer, “Book of John, <Whitmer kept by comma[n]d>” History, ca. 1835–1846, 57-70, The Joseph Smith Papers; Daniel Dunklin, Jefferson City, Missouri, to W. W. Phelps, et al., Kirtland, Ohio, 22 January 1836, William W. Phelps Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL; W. W. Phelps, et al., Liberty, Missouri, to Daniel Dunklin, Jefferson City, Missouri, 7 July 1836, William W. Phelps Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL; Daniel Dunklin, Jefferson City, to W. W. Phelps, et al., Liberty, Missouri, 18 July 1836, William W. Phelps Collection of Missouri Documents, CHL; Memorial of Citizens of Caldwell County, Missouri, 10 December 1838, in “Letterbook 2,” p. 27-33, The Joseph Smith Papers. See also, Mormon Redress Petitions: Documents of the 1833-1838 Missouri Conflict, ed. Clark V. Johnson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992.

[22] See, for example, “The Outrage in Jackson County, Missouri,” Evening and Morning Star, January 1834, 241-44; Declaration on Government and Law, ca. August 1835, in JSP, D4:484; [Oliver Cowdery,] “Abolition,” Northern Times, 9 October 1835, [2]; Joseph Smith to Oliver Cowdery, ca. 9 April 1836, in Brent M. Rogers, Elizabeth A. Kuehn, Christian K. Heimburger, Max H Parkin, Alexander L. Baugh, and Steven C. Harper, eds. Documents, Volume 5: October 1835–January 1838, vol. 5 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2017), 231-243; Warren Parrish, “For the Messenger and Advocate,” LDS Messenger and Advocate, April 1836, 2:295-96; and “The Abolitionists,” LDS Messenger and Advocate, April 1836, 2:299-301.

[23] See, for example, “Universal Liberty,” Times and Seasons, 15 March 1842, 3:723-24; and General Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States (Nauvoo, IL: John Taylor, printer, 1844), 6.

[24] See for example, Letter to the Citizens of Hancock County, ca. 2 July 1842; Ordinance, 5 July 1842, and Petition to Nauvoo Municipal Court, 8 August 1842, in Elizabeth A. Kuehn, Jordan T. Watkins, Matthew C. Godfrey, and Mason K. Allred, eds. Documents, Volume 10: May–August 1842, Vol. 10 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Matthew C. Godfrey, R. Eric Smith, Matthew J. Grow, and Ronald K. Esplin (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2020), 230-36, 355-61. On Nauvoo developments, see Benjamin E. Park, Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of a Religious Empire on the American Frontier (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2020).

[25] See Jordan T. Watkins, “The Revelatory Sources of Early Latter-day Saint Petitioning,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: Washington, DC and Philadelphia, eds. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, forthcoming). See also James B. Allen, “Joseph Smith vs. John C. Calhoun: The States’ Right Dilemma and Early Mormon History,” in Joseph Smith Jr.: Reappraisals after Two Centuries, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Terryl L. Givens (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 73-90. See also, Brent M. Rogers, Unpopular Sovereignty: Mormons and the Federal Management of Early Utah Territory (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 24-30.

[26] See Letter to Hyrum Smith and Nauvoo High Council, 5 December 1839, and Memorial to the United States Senate and House of Representatives, ca. 30 October 1839-27 January 1840, in Matthew C. Godfrey, Spencer W. McBride, Alex D. Smith, and Christopher James Blythe, eds., Documents, Volume 7: September 1839-January 1841, vol. 7 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City, Church Historian’s Press, 2018), 69-70, 138-174; Letter to Martin Van Buren, Henry Clay et al., 4 November 1843, Joseph Smith Collection, CHL; John C. Calhoun to Joseph Smith, 2 December 1843, Joseph Smith Collection, CHL; Joseph Smith to John C. Calhoun, 2 January 1844, Joseph Smith Collection, CHL.

[27] See Carrie Hyde, Civic Longing: The Speculative Origins of U.S. Citizenship (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018), 43-84, quotation on 51.

[28] See Christopher James Blythe, Terrible Revolution: Latter-day Saints and the American Apocalypse (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 42-46.

[29] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 11 March 1844, in JSP, CFM:40, 42.

[30] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 19 March 1844, in JSP, CFM:54.

[31] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 26 Mar. 1844, in JSP, CFM:68, 70. See Rogers, Unpopular Sovereignty, 35.

[32] On Latter-day Saint efforts to use all possible means to gain power to obtain refuge, see Marvin S. Hill, Quest for Refuge: The Mormon Flight from American Pluralism (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1989), 140-41.

[33] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 11 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:91-92.

[34] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 11 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:101.

[35] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 11 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:94.

[36] See, for example, Council of Fifty, “Record,” 11 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:94, 105-106; and Council of Fifty, “Record,” 18 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:117-18.

[37] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 18 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:110-14.

[38] On the blending of republican and theocratic elements, see Park, Kingdom of Nauvoo, 203-205. See also Nathan B. Oman, “‘We the People of the Kingdom of God’: Constitution Writing in the Council of Fifty,” in The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History, eds. Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2017), 60-64.

[39] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 25 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:136, 137.

[40] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 18 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:116.

[41] See Rogers, Unpopular Sovereignty.

[42] Sally Barringer Gordon, The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Conflict in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

[43] Cabet, History and Constitution of the Icarian Community, 258.

[44] See Tsai, America’s Forgotten Constitutions, 72-81.

[45] See W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Prof. Watkins, thank you so very much for this fantastic paper. This is one of the great advantages of an online asynchronous conference—I get to hear/read papers that I might have missed due to scheduling conflicts.

When I teach about antebellum utopianism, I usually teach about the Fourierists rather than the Icarians, partly because the Fourierists founded La Rénunion, a colony that became the Oak Cliff town/neighborhood of Dallas (so, a local angle) but also because of their countercultural views of marriage and family life. The basic through-line in my teaching of this period is that utopianism in various forms was an attempt to grapple with the problem of how to survive in a world of “individualism”–in faith, in family life, in the economy. When so much of one’s fate seemingly rested upon the will and choices of the self, but selves had less and less power to effect their will in a rapidly changing world, people sought new ways of banding selves together. In this context, I teach Mormonism as a successful (after much struggle) utopian movement as well as an American religion in its own right.

But your framing of the Icarians alongside the Mormons is challenging me to look again at that framing and to consider some insider/outsider possibilities. I love your point about how Garrison could afford to be a come-outer because he implicitly belonged, whereas Douglass was not accepted as fully belonging and so could not afford to call for alienation/separation. One wonders how things would have turned out had Douglass burned the Constitution instead of Garrison. Your discussion of the Mormon understanding of the US constitution and their own constitution does a great job of underscoring the fact that the Mormons were not “come outers” by choice, but had to take up that mantle.

Finally, I’m very intrigued by your point about how belief in the divine inspiration of the Constitution presumes/assumes that there is an authority greater than the Constitution. Greater than the law is the lawgiver. Even though there are plenty of non-Mormons who say the Constitution was “divinely inspired,” I’m not sure they are interested in invoking a Lawgiver so much as discounting/denying a need for any further guidance or wisdom.

Anyway, this was a great, provocative paper. Thanks a lot for bringing it to us.

L.D. Burnett, thank you for your thoughtful engagement with my post. I did think about the Fourierists when I began writing the paper, and certainly there are other Utopian groups who demonstrated greater similarities with the Mormons than the Icarians, but I decided to use them in large part because of the group’s history in Nauvoo, but also because of their written Constitution.

Your comment about insider/outsider possibilities is precisely what I’m interested in exploring further. I should note that I borrowed T. Gregory Garvey’s insight on Garrison and Douglass, but I think that the Latter-day Saints also had to consider constitutional means and could not afford to entirely cast aside the Constitution. However, and I hope this is clear in the post, the Mormons had much greater access to American society than did free blacks such as Douglass.

And yes, I do think there’s something unique about the Mormon view of the Constitution as divinely inspired, as they root that belief in revelation. However, as you gathered from my post, this leaves open the possibility of setting the Constitution aside, which they did, if only momentarily. I think this idea has been a bit lost in light of subsequent developments.

Thank you for your engagement.

This is fascinating stuff, Jordan. I was not aware of the Icarian constitution–so ironic that we have two examples of constitution-making in one place!

I’m also struck by how the Mormons in Nauvoo used a concept of a “living constitution” in a number of settings, including with the women’s relief society and the capitalistic mercantile organization. In each cases, they referred to the founders as a “living constitution.” Do you find that concept common throughout America at the time? It seems Douglass comes close to that with his generational interpretation of the Constitution, but doesn’t use the same language.

Thank for your comment, Ben.

I have not seen the idea of a “council as constitution” in antebellum America outside of the Mormon contexts you mentioned. I would not be surprised to find this idea elsewhere in American society and would very much like to know if others have seen this. In the Mormon case, I think this indicates the rising importance of councils during the 1830s and 1840s.

It is perhaps also notable that while we do begin to see interpretations of the US Constitution as a kind of living text during this period, the Mormons don’t seem to engage in that kind of reading. Perhaps this relates to their literalist readings of scripture, which of course was not unique to them.