In recent weeks, President Trump has spent a great deal of time articulating a specific and extreme vision of American patriotism. This vision asks us to remember and celebrate only the most idealized American histories and stories, and defines any deviation from those celebrations as nothing less than unpatriotic hate.

Trump expressed this absolute form of patriotism in the September 17th speech announcing his “Patriotic Education” Commission, calling the New York Times’ 1619 Project “a crusade against American history,” “toxic propaganda,” and “a form of child abuse.” He claimed that “patriotic moms and dads are going to demand that their children are no longer fed hateful lies about this country.” And he did so again in his recent Columbus Day proclamation, arguing that the “extremists” who would “replace discussion of [Columbus’] vast contributions with talk of failings … seek to revise [history], deprive it of any splendor, and mark it as inherently sinister,” and that in response “we must teach future generations about our storied heritage.”

In my forthcoming book Of Thee I Sing: The Contested History of American Patriotism, I define this form as mythic patriotism. This extreme, exclusionary form of celebratory patriotism both relies on myths of an idealized past and uses phrases like “love it or leave it” to exclude any Americans who do not fully embrace those myths. Such mythic patriotism is far too often what we have in mind when we describe something or someone as “patriotic,” which poses a problem as this perspective is clearly divisive, often destructive, and like the myths on which it relies needs challenging from those of us who see the nation and our role in it differently.

In my forthcoming book Of Thee I Sing: The Contested History of American Patriotism, I define this form as mythic patriotism. This extreme, exclusionary form of celebratory patriotism both relies on myths of an idealized past and uses phrases like “love it or leave it” to exclude any Americans who do not fully embrace those myths. Such mythic patriotism is far too often what we have in mind when we describe something or someone as “patriotic,” which poses a problem as this perspective is clearly divisive, often destructive, and like the myths on which it relies needs challenging from those of us who see the nation and our role in it differently.

But there’s another prominent form of celebratory patriotism, one that seems to represent a more unifying alternative to mythic patriotism but that is in its own way just as limiting. Exemplifying this form of celebratory patriotism was Marilyn Robinson’s recent New York Times op ed “Don’t Give Up on America,” with its metaphorical vision of America as a family that has lost its way but still deserves our love. If we better remember that shared ideal, Robinson argues, we can find our way back to a better, more genuinely collective version of our national family.

Robinson’s vision of patriotism is undoubtedly more positive and productive than Trump’s, and has the potential to be more widely shared. But such celebratory patriotism suffers from a significant flaw: it comes from a place of privilege that imagines America has at some point lived up to its ideals for all Americans. And in that imagining there lies the danger of a corresponding nostalgia, a longing for a mythic, still idealized past as the answer to present struggles and the model for a future we can work toward.

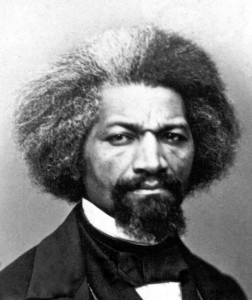

As writers and artists of color have been pointing out for as long as the United States has existed, the truth is that there has always been a significant gap between America’s ideals and its realities, between our imagined community and the lived experience for far too many Americans. No American text better expresses that gap than a passage in Frederick Douglass’s masterful 1852 speech “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” Having traced the holiday’s Revolutionary emphases, the fugitive slave Douglass addresses his audience with righteous fury:

“I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony.”

While Douglass goes on to trace the moment’s most painful realities, he nonetheless ends his speech, as he puts it, “where I began, with hope…Notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country.” That combination of criticism and hope makes Douglass’s speech an embodiment of what I define as critical patriotism: an embrace of the nation’s ideals that at the same time highlights all the ways we’ve fallen short of them, with a goal of moving us closer to that as-yet-unrealized, best version of ourselves and our community.

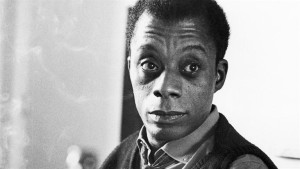

No quote more succinctly and perfectly expresses that critical patriotism than does a line of James Baldwin’s, from his 1955 essay collection Notes of a Native Son: “I love America more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” Baldwin’s key phrase is “exactly for this reason,” a recognition that the two parts of critical patriotism cannot be separated, that they represent instead an intertwined perspective that criticizes the nation’s failings precisely due to the patriotic love which wants and works for something better.

We can trace the legacy of such critical patriotism through so many inspiring figures and communities, moments and stories, across American history. We can find it in contemporary voices like that of Colin Kaepernick, who when he began kneeling during the national anthem in August 2016 argued, “To me [racial inequality] is something that has to change and when there’s significant change and I feel like that flag represents what it’s supposed to represent in this country, I’ll stand.”

We can trace the legacy of such critical patriotism through so many inspiring figures and communities, moments and stories, across American history. We can find it in contemporary voices like that of Colin Kaepernick, who when he began kneeling during the national anthem in August 2016 argued, “To me [racial inequality] is something that has to change and when there’s significant change and I feel like that flag represents what it’s supposed to represent in this country, I’ll stand.”

And no 21st

century American text better reflects such critical patriotism than the aforementioned 1619 Project. As journalist and project editor Nikole Hannah-Jones puts it in her introductory essay, linking her father’s resilience and steely-eyed optimism to the long legacy of African American critical patriotism

maintained in the face of systemic racism and violence, “It is black people who have been the perfecters of this democracy.”

Those of us who hope to help further perfect this democracy unquestionably have to challenge Trump’s mythic patriotism and the exclusionary narratives upon which it relies. But we also and just as importantly have to highlight the privileged, nostalgic limits to Robinson’s celebratory version. In so doing, we can extend and amplify the legacy of these models of critical patriotism—inspiring American voices that can help us chart a path forward toward a more perfect union.

__________

Ben Railton is Professor of English and American Studies at Fitchburg State University and the author of six books, most recently Of Thee I Sing: The Contested History of American Patriotism (January 2021).

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

PS. Just wanted to make sure to say that, even more than usual, I welcome responses, comments, thoughts of all kinds for my own continued thinking about these topics. Thanks!

Ben

I am curious as to how, or even if, you distinguish between patriotism and nationalism. When I think of the messianic if not psychopathic cult of Trump, perfervid, often religious nationalism comes to mind, not patriotism, which I associate with those willing to serve their country in one way or another, or to support the common or public good, or make contributions to the welfare, well-being and happiness (or flourishing) of their compatriots. Religious nationalism is anti-Liberal and anti-democratic, patriotism need not be and often in fact is not. Perhaps the lines are not easy to draw here and in any case, would be permeable if not porous, making the distinction less important than I believe it is or should be. Thank you.

Thanks very much for your comment and for raising those important categories, Patrick. I agree, and would indeed want at least to closely link what I call “mythic patriotism” to both nationalism and chauvinism (the whole “us vs. them and we are better/the best” set of narratives).

Given that “patriotism” is so often used as a shorthand for a combination of celebratory and mythic patriotism, both by those supporting that vision and even by those critical of it (which I think is why so many critics reject the idea of patriotism entirely), I believe it’s important to engage that longstanding definition. But yes, I would be more than fine if that definition became synonymous with chauvinistic nationalism, leaving patriotism over for the more active patriotic (service and sacrifice) and critical patriotic forms.

Ben

The division of patriotism into these different varieties seems useful, at least in the American context, and probably others as well.

On the question of nationalism vs. patriotism, a 1971 article by Jacques Godechot in the journal Annales historiques de la Révolution française distinguishes between the two in the context of French history. A full cite for the article can be found in the bibliography of R. Brubaker, Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany (1992).

The patriotic Right has always criticized multitudes of American things, so isn’t logically immune to its own attacks on our Kaepernicks. But as Walter Russell Mead noted in his 1999 article “Foreign Policy and the Jacksonian Tradition” (which I urge all to read), logic and political coherence are not to be found here — only a set of codes one violates at one’s peril. Customs outweigh rights, symbolism may count more than substance, and patriotic theater is obligatory, while racial, ethnic and sexual identity qualify membership in the tribe.

Mead clarified what still mystified me about the politics of so many people I grew up around, and right-wing populism in general. Further elucidation came from “The Common Cause: Creating Race and Nation in the American Revolution” by Robert G. Parkinson — whose big takeaway is that ongoing hostility to Native Americans and Blacks dates to, or was exacerbated by, propaganda for independence from Great Britain. Presses up and down the colonies spread scare stories and exaggerated real incidents of redcoats bribing the former to kidnap and scalp Whites, and the latter to murder their masters in their beds.