Editor's Note

We are pleased to publish this guest post by Mark Rice.

Mark Rice is Professor of American Studies at St. John Fisher College in Rochester, New York. He is the author of two books, Through the Lens of the City: NEA Photography Surveys of the 1970s (University Press of Mississippi, 2005), and Dean Worcester’s Fantasy Islands: Photography, Film, and the Colonial Philippines(University of Michigan Press, 2014).

On September 17, in a speech

commemorating Constitution Day, President Trump laid out his vision for how the history of the United States should be taught. He told his audience that he would sign an Executive Order to create “a national commission to promote patriotic education.” The name of the commission is the 1776 Commission. The president said his mission is “to defend the legacy of America’s founding, the virtue of America’s heroes, and the nobility of the American character.”

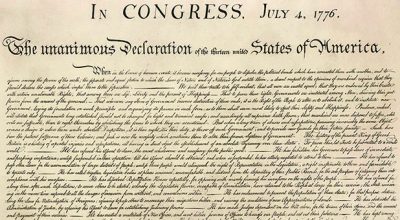

The Declaration of Independence

A few weeks prior, I had talked with my students about the ways in which Erika Lee’s book, America for Americans, challenges some of the dominant narratives of our nation’s past, specifically the narrative of the United States as a country that has always welcomed immigrants. Back then I briefly mentioned something called the 1619 Project as another effort to reframe our nation’s past by drawing attention to the arrival of the first enslaved Africans as being as important as, if not more important than, 1776, the year of the Declaration of Independence. In his speech, the president claimed that the 1619 Project was “totally discredited” and “ideological poison, that if not removed, will dissolve the civic bonds that tie us together, will destroy our country.”

The president summed up his vision of how American history should be taught in the final lines of his speech: “From Washington to Lincoln, from Jefferson to King, America has been home to some of the most incredible people who have ever lived. With the help of everyone here today, the legacy of 1776 will never be erased. Our heroes will never be forgotten. Our youth will be taught to love America with all of their heart and all of their soul. We will save this cherished inheritance for our children, for their children, and for every generation to come.”

So, in his speech, President Trump laid out a stark contrast between the two dates in question: 1619 and 1776. He dismissed the significance of the first while elevating the importance of the second.

I outlined these characteristics of Trump’s speech for my students the day after he gave it, and then I talked to them about an idea at the core of Trump’s speech: love of country. Below is the text of my remarks.

____

I want to take just a bit of class time today to address President Trump’s speech. My first awareness of his speech was from a tweet that quoted the line: “Our youth will be taught to love America with all of their heart and all of their soul.” It struck me—it strikes me—as a statement that goes against the very nature of teaching and of love.

Let’s start with the phrase “Our youth will be taught to love.” Can we be taught to love? We can certainly LEARN to love, but can we be TAUGHT to love? Imagine someone telling you, “You will love me. I will teach you to love me.” How would you respond to that? While you might find it a charming if somewhat awkward romantic gesture, I think that if you confided in a trusted friend what you were told, they would see it as a red flag and would advise you to be very careful around that person.

In his first letter to the Corinthians, Saint Paul said that “love is patient and kind; love does not envy or boast; it is not arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice at wrongdoing, but rejoices with the truth.” Is this humble kind of love, a love that seeks to understand and celebrate the truth and is not boastful, the love that President Trump wants our youth to learn? Maybe it is, but his speech didn’t reflect that sort of humble love.

When President Trump said that our youth will be “taught to love America with all of their heart and all of their soul,” what he meant is that they will be taught to be patriotic, as the very definition of patriotism is “love of country.” Can a person be taught to love their country? Can people be made to be patriotic? To me, the notion of being “taught to love America” feels as false and coercive as any other effort to force-teach love.

If we accept the premise that love of country is good, how would we teach children in such a way that they might learn to love the country in a way that is not arrogant and that rejoices in truth?

Do we learn to love somebody by seeing only one dimension of them, or do we learn to love somebody by recognizing their shortcomings as well as their bright spots? Young children often believe that their parents are perfect, and they love them blindly. That’s an important evolutionary development, I imagine, as the very survival of small children depends on their wide-eyed acceptance of the perfection of whoever is taking care of them.

But think of more mature examples of love, perhaps a love you feel for a romantic partner, or a close friend, or a parent, a love that recognizes in those people their human faults and frailties alongside those things that make them shine in your eyes. That is a richer, deeper sort of love, isn’t it?

Why can’t the same be true of love of country? The historian, Kevin Kruse, tweeted in response to President Trump’s speech: “History that exalts a nation’s strengths without ever examining its shortcomings, that prefers feeling good rather than thinking hard, that seeks simplistic celebration over a full understanding–well, that’s not history; that’s propaganda.”

In his 1955 book, Notes of a Native Son

, James Baldwin, one of the twentieth-century’s keenest intellects and writers wrote: “I love America more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” Is President Trump advocating for this form of love-of-country, a love built on the recognition of the country’s many flaws in order to work to overcome those flaws? I wish that is what he meant, but his speech suggested otherwise. His speech suggested a reaffirmation of the dominant narrative that we have been at the center of our nation’s story for more than two hundred years: the narrative of 1776.

The 1619 Project is a product of that vein of love that Baldwin insists on: a love based on an effort to see things with clearer eyes than we have before. Now, I don’t know if the 1619 Project is 100% right in its arguments about American history, but my own love of America compels me to take it seriously, to be willing to consider its merits and to weigh its evidence, not to dismiss it out of hand as an existential threat to the country. Indeed, believing that any history curriculum can “destroy our country” both inflates the power of the history classroom and shows little faith in the strength of the nation.

My own love of America compels me to ask hard questions about its dominant narratives in order to better understand its truths. I try to center this in my teaching, to help young adults better understand the bright spots as well as the flaws of the United States. For those students for whom love of country is deeply important, I hope that they come out of my classes with a richer, more complex, more mature love of country.

Twice in his speech–in the lead up to his criticism of the 1619 Project, and in his culminating lines—President Trump invoked Martin Luther King. In the paragraph before he labeled the 1619 Project as “ideological poison,” President Trump said, “We embrace the vision of Martin Luther King, where children are not judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

That is Dr. King’s most famous line, but it is a paraphrase from a longer passage. The full quote reads, “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” When Dr. King spoke those words in his famous 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, he knew that he did not live in that nation. Do we live in that nation now? By saying “are not judged by the color of their skin,” instead of “will not be judged by the color of their skin,” President Trump suggested that we have achieved racial equality in America. I wish that were so, but there is scant evidence that we have.

People who know the life and works of Dr. King often note that the scope of his legacy has diminished, that for many Americans he has become reduced to that one line and to the deep Christian faith that he embraced. Those parts of who he was have become part of our dominant narrative. But Dr. King was far more complex than just that line and his faith, and so I will honor President Trump’s invocation of Dr. King by quoting him some more, this time from his 1967 speech, “The Three Evils of Society.”

For example: “We have deluded ourselves into believing the myth that Capitalism grew and prospered out of the Protestant ethic of hard work and sacrifice; the fact is that Capitalism was built on the exploitation and suffering of black slaves and continues to thrive on the exploitation of the poor – both black and white, both here and abroad.”

And: “We must … realize that the problems of racial injustice and economic injustice cannot be solved without a radical redistribution of political and economic power.”

And: “I suspect that we are now experiencing the coming to the surface of a triple prong sickness that has been lurking within our body politic from its very beginning. That is the sickness of racism, excessive materialism and militarism. Not only is this our nation’s dilemma it is the plague of western civilization. As early as 1906 W. E. B DuBois prophesized that the problem of the 20th century would be the problem of the color line; now as we stand two-thirds into this crucial period of history we know full well that racism is still that hound of hell which dogs the tracks of our civilization. Ever since the birth of our nation, White America has had a Schizophrenic personality on the question of race, she has been torn between selves. A self in which she proudly professes the great principle of democracy and a self in which she madly practices the antithesis of democracy. This tragic duality has produced a strange indecisiveness and ambivalence toward the Negro, causing America to take a step backwards simultaneously with every step forward on the question of Racial Justice….There has never been a solid, unified and determined thrust to make justice a reality for Afro-Americans. The step backwards has a new name today, it is called the white backlash, but the white backlash is nothing new. It is the surfacing of old prejudices, hostilities and ambivalences that have always been there. It was caused neither by the cry of black power nor by the unfortunate recent wave of riots in our cities. The white backlash of today is rooted in the same problem that has characterized America ever since the black man landed in chains on the shores of this nation.”

Dr. King spoke these lines in 1967, but they sound to me as though they could have been spoken today. The country that he described then is with us still. More importantly, Dr. King tells us that the problems that plague our country reach back to the very beginning of our country, to the first moment that “the black man landed in chains on the shores of this nation.” That was in the year 1619, the year that the 1619 Project asks us to take seriously.

So, while President Trump wants to pull Dr. King into the narrative of 1776, Dr. King insists on the importance of 1619 in our nation’s history. Dr. King’s own words reject the call of President Trump to fall back upon the dominant narratives of who we are.

Dr. King tells us that we need to seek our answers elsewhere, and so I will finish with more of his words: “[W]e believe, we hope, we pray that something new might emerge in the political life of this nation which will produce a new man, new structures and new institutions and a new life for mankind. I am convinced that this new life will not emerge until our nation undergoes a radical revolution of values. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people the giant triplets of racism, economic exploitation and militarism are incapable of being conquered. A civilization can flounder as readily in the face of moral bankruptcy as it can through financial bankruptcy. A true revolution of values will soon cause us to question the fairness and justice of many of our past and present policies. … A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth, with righteous indignation it will look at thousands of working people displaced from their jobs, with reduced incomes as a result of automation while the profits of the employers remain intact and say, this is not just. It will look across the ocean and see individual Capitalists of the West investing huge sums of money in Asia and Africa only to take the profits out with no concern for the social betterment of the countries and say, this is not just. It will look at our alliance with the landed gentry of Latin America and say, this is not just. A true revolution of values will lay hands on the world order and say of war, this way of settling differences is not just. This business of burning human being with napalm, of filling our nation’s home with orphans and widows, of injecting poisonous drugs of hate into the veins of peoples normally humane, of sending men home from dark and bloodied battlefields physically handicapped and psychologically deranged cannot be reconciled with wisdom, justice and love. A nation that continues year after year, to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.”

Belief, hope, and prayer for a revolution of values that will lead us to question the fairness of the policies of the past in order to develop new structures and new institutions and a new life for humanity that promotes social uplift. I wonder: Will that vision of America be included in the presidential commission to promote patriotic education?

0