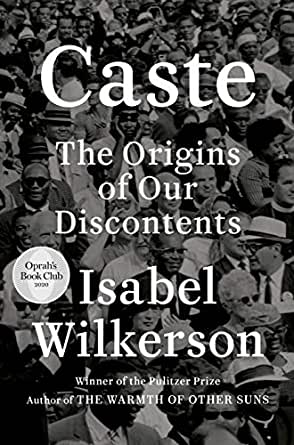

The Book

Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (New York: Random House, 2020)

The Author(s)

Isabel Wilkerson

What’s in a name—or, in this case, what’s in a caste? This is the central question of Isabel Wilkerson’s newest book, Caste. For Wilkerson, her newest long-term project tries to re-consider how we talk about racial classification in American society. In the process, she compares race and caste in the United States to India and Nazi Germany. In such comparisons, she reveals as much about our own country as she does those—but it remains to be seen how (and perhaps why) such a reclassification is so important. Wilkerson’s project is a valuable statement about the intellectual history of race as it stands in 2020. It also reminds us how muddled the idea of race has been—and continues to be.

Early in Caste, Wilkerson describes America as “an old house,” thinking of it as a place that has festering problems with its structure, ones that most people simply don’t want to deal with (15). The last decade of writing and thinking about race approaches it in much the same way. Just this year, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the upsurge in Black Lives Matter protests, and another consequential election cycle (the latest iteration in the “Most important election of our lifetimes” election) we’ve seen numerous works on race and the American condition. Ta-Nehisi Coates guest-edited an issue of Vanity Fair magazine which wrestled with the problem of racism in America. “Whiteness thrives in darkness,” Coates writes, arguing for the continued need to shed light on the intractable problem of race in American society.

This is what Wilkerson attempts to do. But by using the terminology of “Caste,” she wants her reader to rethink what we all assume about life in the United States. She recalls how in her previous book, The Warmth of Other Suns, she was describing an “American caste system, an artificial hierarchy in which most everything that you could and could not do was based upon what you looked like and that manifested itself north and south (27).” Seeing African Americans as on the lowest rung of caste compels the reader to consider just how far the nation has come.

Caste, like so many other writings about race in recent years, is difficult to disentangle from the presidency of Donald Trump. Wilkerson’s book is peppered with stories about racism and life during the Trump years, further illustrating her point about a caste system in America. Of course, this should not be a surprise—could one, for example, completely extricate James Baldwin’s writings about race from the Civil Rights Movement of the early 1960s, the Black Power struggle of the late 1960s, or the Age of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s? Nonetheless, it does offer something for both intellectual historians now and in the future to consider when developing an intellectual history of race set during our present moment of interlocking crises.

Wilkerson’s stories—thanks in large part to her clear and engaging writing—bring to life her meaning of caste. For Wilkerson, caste can cross class lines, as illustrated by the times in her life where her gender and skin color have meant people did not take her seriously as a reporter for the New York Times. They are stories likely familiar to African Americans in the middle and upper classes of American society. Being treated harshly on a flight by a white co-passenger, and receiving no help from an African American steward on the plane; losing an interview request because the interviewee did not believe a Black woman would be sent by the Times

to interview him; and so forth. On the surface, they may appear to be problems only a Black professional would experience—but for Wilkerson, they help to illuminate the deeper problem of racial caste in American society.

Caste leans heavily on recent and far-reaching works on race and racial classification. Scholars such as Ian Haney Lopez and Eduardo Bonilla Silva, Kenneth Stampp and W.E.B. Du Bois, and so many others, buttress Wilkerson’s argument. But perhaps no scholar stands out more for their usage in this book than Allison Davis. His work on the American South’s racial caste system, Deep South: A Social Anthropological Study of Caste and Class, was a critical work on race in America that was somewhat overshadowed by Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma. Nonetheless, the life story of Davis—chronicled in David Varel’s biography—also supports Wilkerson’s argument about caste. A man of Davis’ talents struggling to find support for his research simply due to his being Black was but one more sad story of racism in American life not only holding back a person of color but, ironically, hurting white Americans who could have benefited from such research as well.

One problem with Caste is that, while it places an important (and understandable) emphasis on Black Americans as being at the bottom of the American caste system, it virtually ignores Native Americans. Where are they to be accounted for in such a “caste” system as ours? To Wilkerson’s credit, however, she does consider where such a caste system may be going. Her answer is not necessarily cheerful. “The definition of whiteness,” Wilkerson argues, “could well expand to confer honorary whiteness to those on the border—the lightest-skinned people of Asian or Latino dissent or biracial people with a white parent, for instance—to increase the ranks of the dominant caste” (382). Here, Wilkerson builds off the previous works of scholars such as Bonilla-Silva to worn of a recrafting of caste—for the sake of keeping whiteness on top.

Ultimately, Caste is worth reading if you’re curious about how America got to this current crisis over racial identity and classification. I did find Wilkerson’s telling of how she could discern who was of lower caste in a Indian context at a conference fascinating: noticing which academics and scholars seemed to dominate discussion showed her who was from the more powerful castes, while those academics who deferred and seemed almost intimidated quickly screamed to her lower caste. However, this book may say as much about caste within Black American society. Wilkerson takes great pains to make it clear that the caste system affects all Black Americans, regardless of their class status. But she also points to studies that argue, for example, that Black men and women suffer from higher rates of hypertension, stress, and other related health maladies than their poorer brethren due to the stresses of the class system. Referring to Black people who’ve “made it” in society as “shock troops on the front lines of hierarchy,” Wilkerson makes it clear that caste in America is very much part of our racial construct.

I find the book an intriguing read during an era when the American Left is torn over questions of racial and class consciousness, when liberals digest and debate the idea of “white privilege” and “white fragility,” and when a president from the conservative party in the United States criticizes “political correctness” and “Critical race studies.” Wilkerson deals with this question in a long, historical debate that includes people such as Oliver Cox and, Myrdal, and Davis. I will come back to those questions in future essays, but for now one thing is certain: writing about race and identity in 2020 means battling a complicated system of classification that Americans, it seems, cannot escape. We can only reshape and reconfigure it.

About the Reviewer

Robert Greene II is an Assistant Professor of History at Claflin University, as well as blogger and Book Reviews editor for the Society of U.S. Intellectual Historians. Dr. Greene has also been published in The Washington Post, The Nation, Jacobin, In These Times, Oxford American, and other publications.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

The question I asked of this book was a little different: Is “caste” a better/easier concept to teach my undergrads than is the concept of “structural racism”? Because it’s too hot, too misunderstood, too associated with hate or with white supremacy as doctrine, does the word ‘racism’ become an obstacle to understanding ‘structural racism’? Kendi has addressed this problem by redefining racist not as something someone definitively is or isn’t, but as something anyone can be at any moment when they support ideas that justify racial inequities or when they support policies that result in racial inequities. DiAngelo gets at this, too, in *White Fragility,* which is all about the emotional defenses triggered by the words racism and racist. I think Kendi’s redefinition is an especially helpful adjustment in approaching old topics in a new way. Although I haven’t tried it yet, I think it could be productive to ask students to consider how King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech makes the locus of change the individual human heart rather than the invisible piers and beams of a society. (And then give them one of King’s other speeches.) I very much enjoyed Wilkerson’s book. She has a real gift for metaphor. For me, though, the case is still out on whether caste is the better pedagogical choice. If you have an opinion on that, Robert, I’d be happy to hear it.