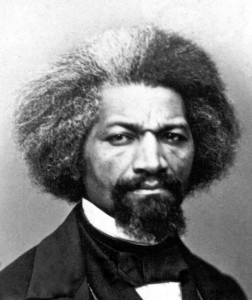

The Frederick Douglass Ireland Monument, by Andrew Edwards

In My Bondage and My Freedom, published in 1855, Frederick Douglass revisits his own experiences as a youth who came to understand what it meant to be enslaved for life. He links this growing awareness with his thirst for knowledge and describes his enlightenment about his own condition alongside his passionate but mostly clandestine self-cultivation in the arts of reading, writing, and oratory.

These are themes Douglass had discussed in his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself (1845). In that earlier telling, we meet the young gaggle of white boys, some sons of immigrants, who were Douglass’s associates and comrades in the bustling streets of Baltimore down by the docks and wharves. We learn in that first narrative that Douglass sometimes traded the freshly baked bread of his masters’ household for a lesson in reading or writing from “the poor white children in our neighborhood,” the “hungry little urchins” who gave him in return “that more valuable bread of knowledge.” Douglass noted in his 1845 narrative that when he told his young companions that he knew he would be enslaved for life, “These words used to trouble them; they would express for me the liveliest sympathy, and console me with the hope that something would occur by which I might be free” (Narrative, chapter VII).

Writing a decade later, Douglass had much more to say about those rough-and-tumble street urchins who were his companions in childhood. In this later telling, we learn that while these young street toughs were glad to trade a lesson for some bread, many of them were just as happy to teach him without any compensation at all. And Douglass expanded upon the conversations he had with his “warm-hearted little playfellows” about slavery.

I frequently talked about it—and that very freely—with the white boys. I would, sometimes, say to them, while seated on a curb stone or a cellar door, “I wish I could be free, as you will be when you get to be men.” “You will be free, you know, as soon as you are twenty-one, and can go where you like, but I am a slave for life. Have I not as good a right to be free as you have?” Words like these, I observed, always troubled them; and I had no small satisfaction in wringing from the boys, occasionally, that fresh and bitter condemnation of slavery, that springs from nature, unseared and unperverted. Of all consciences, let me have those to deal with which have not been bewildered by the cares of life. I do not remember ever to have met with a boy, while I was in slavery, who defended the slave system; but I have often had boys to console me, with the hope that something would yet occur, by which I might be made free. Over and over again, they have told me, that “they believed I had as good a right to be free as they had;” and that “they did not believe God ever made any one to be a slave.”

Just as he had done in 1845, so in 1855, Douglass declined to give the boys’ names, because, he said, “it is almost an unpardonable offense to do any thing, directly or indirectly, to promote a slave’s freedom, in a slave state.”

As I read this passage about the consciences of these boys, their sense of rough egalitarianism that springs from nature, their beliefs about natural rights and about God’s will – that young Fred had a right to be free, that slavery had nothing to do with God’s will—and their fresh and bitter condemnation of slavery, as well as the risk to them of doing so, I saw in Douglass’s 1855 description of these hungry urchins a clear antecedent to Huck Finn. In just a couple of paragraphs describing the moral awakening of himself and his comrades confronting the fundamental immorality of the slave system, Douglass had sketched out the fundamental moral dilemma that would later become the beating heart of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn

, the moral dilemma of its titular character.

I found myself wondering: did Mark Twain read Frederick Douglass? I reached out to Dr. Erin Bartram, School Programs Coordinator for the Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, Connecticut. Erin has presented at our conference before and is a wonderful, collegial scholar. I asked her via Twitter, “what can you tell me about whether/when Mark Twain read Frederick Douglass?” She was quick to respond, “How about met him and recounted conversations?” She pointed me to the marktwainproject.org website where Twain mentions in a letter to his fiancée that he had visited with Douglass. In a letter to President James Garfield, Twain speaks of his admiration of Douglass for his “high and blemishless character” and for “his brave long crusade for the liberties & elevation of his race.” Twain adds, “He is a personal friend of mine.”

I found myself wondering: did Mark Twain read Frederick Douglass? I reached out to Dr. Erin Bartram, School Programs Coordinator for the Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, Connecticut. Erin has presented at our conference before and is a wonderful, collegial scholar. I asked her via Twitter, “what can you tell me about whether/when Mark Twain read Frederick Douglass?” She was quick to respond, “How about met him and recounted conversations?” She pointed me to the marktwainproject.org website where Twain mentions in a letter to his fiancée that he had visited with Douglass. In a letter to President James Garfield, Twain speaks of his admiration of Douglass for his “high and blemishless character” and for “his brave long crusade for the liberties & elevation of his race.” Twain adds, “He is a personal friend of mine.”

I didn’t find any explicit mentions of Twain having read My Bondage and My Freedom, but it seems quite likely that he would have, or that he would have heard Douglass speak about his quest to learn to read and about the poor white boys whose consciences rebelled at the thought of slavery as somehow the will of God. And it seems even likelier that Twain and Douglass would have talked about some of these things as friends.

I am neither a Twain scholar nor a Douglass scholar, so I don’t know the literature on their relationship in life or on the page. From the cursory searches I have been able to do, it seems that much scholarly conversation revolves around reading or re-reading Jim in relation to Douglass, or discussing Douglass’s possible influence on how Twain conceived of Jim’s character. But I haven’t found anything yet that discusses how Douglass may have shaped Twain’s conception of Huck. If there’s some scholarship on this, I’d be glad for someone to point me to it.

I am not saying that Mark Twain cribbed the character of Huck Finn from Frederick Douglass. I am saying that Frederick Douglass probably understood the character of a boy like Huck Finn long before Mark Twain did, and Douglass’s clarity of vision in revisiting his own boyhood may have helped Twain envision another most memorable American boy.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

“If there’s some scholarship on this, I’d be glad for someone to point me to it.”

If you’re serious, I will happily give you a bibliography of the things I’ve read that I’ve found most helpful in thinking through these issues! There’s some good work, but there’s so much more to do.

I am serious! I’m writing about Douglass in connection with the idea of Western Civilization, and I should probably write about Twain in the same vein. It would be nice to strengthen my sense of the through-line with a sturdy bibliography of secondary sources. Thank you!