Editor's Note

The views expressed in this blog post do not reflect the views of the blogger’s employer.

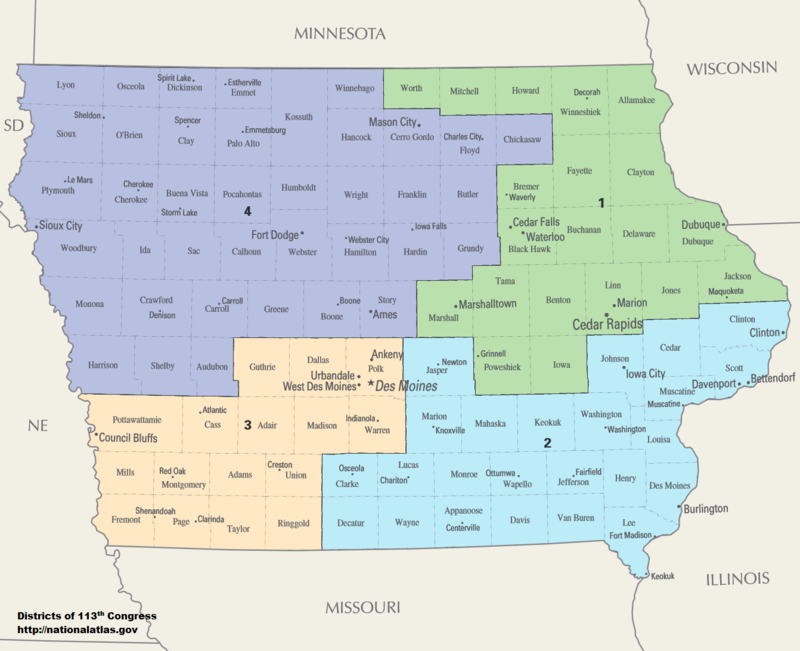

Two days ago, Steve King, the controversial representative from Iowa’s 4th District, lost his bid for a tenth term in Congress. The commentary that followed focused more on King’s loss than on former state senator Randy Feenstra’s win. Headlines like “Steve King, House Republican with History of Racist Remarks, Loses Primary” or “Steve King– Who Embraced White Supremacy– Loses Amid Nationwide Protests Against Racism” have highlighted both King’s history of racist remarks and the timing of his defeat. Other stories have focused on Feenstra’s support from major donors and prominent Republicans, but lamented how King’s primary challengers, Feenstra included, focused their critiques on the King’s ineffectiveness rather than his history of using racist rhetoric.

The explanations for Feenstra’s win have focused on King’s failures, the influence of GOP powerbrokers who lined up behind Feenstra, and the influence of outside money. But a careful attention to the history of the region suggests that at least one more factor may have influenced the outcome: Feenstra’s Dutch heritage. I don’t want to overstate my case here, but I think there is an argument to be made that the margins Feenstra ran up in Dutch enclaves ultimately pushed him over the top.

Feenstra walloped King in the Dutch areas in the northwest corner of the state. In a crowded primary, the only counties where Feenstra received an outright majority of the votes were in the four counties in Iowa’s farthest northwest corner. In Iowa’s most reliably Republican county, Sioux County, he did especially well. Sioux County accounted for nearly 10% of the votes cast in the district’s Republican primary and a full 18% of Feenstra’s vote total. It provided Feenstra with his most dominant performance of the night, trouncing King by over 66 points.

Northwest Iowa is Feenstra’s home turf. He represented parts of this area in Iowa’s General Assembly, and on the face of it, that may explain Feenstra’s advantage; however, King failed to run up a similar margin in his native Crawford County, though he did come out on top there. None of the other challengers carried their home counties, despite being prominent members of their communities. Feenstra did exceedingly well on his home turf as compared to his opponents.

For the past 150 years, these four rural counties have been one of the major hubs of Dutch-American life in the United States. Many communities in this region share a common history that anchors them and encourages them to think about themselves in particular ways, with clear conceptions of insiders and outsiders. Dutch bingo is a favorite past time in the area—a game aimed at figuring out how any two Dutch-Americans are related, premised on the assumption that somehow everyone of Dutch descent in these communities must share a familial connection. Feenstra is an undeniably Dutch last name, which offers him the consummate insider status in these four counties, particularly in the region’s anchor of Sioux County.

Historians of immigration and Dutch-American history have noted that as the Dutch have acculturated, they have remained remarkably loyal to one another and have continued to find their identity in their ethnicity generations after immigrating.[1] That persistence is obvious during Tulip-themed celebrations in the spring, Sinterklaus festivities in December, or in the local high school’s mascot—the Dutchman. It’s also possible that it was present in Tuesday’s election results, but to find it, you have to know the history of ethnic identity and balance that against the increasing importance of partisan loyalty.

In 1870, the first Dutch settlers arrived in Sioux County, Iowa, and from their mother colony in Orange City, they spread out to numerous smaller communities, especially in neighboring Lyon and O’Brien Counties. Since their arrival in region, and even earlier when they had settled elsewhere in south central Iowa and western Michigan, these immigrants proved themselves to be shrewd students of U.S. politics, and time and again, they demonstrated their loyalty first and foremost to one another. Underlying Tuesday’s vote totals, a history of ethnic identity shapes the politics in these counties.

In northwest Iowa’s early days, Dutch loyalty to their kin was explicit. In the lead up to local elections in 1876, the editor of the local paper acknowledged that a difference of political opinion existed among the Dutch but encouraged them to “obtain a full voice, in order to show that the Dutch are one! ONE! ONE!”[2] Six year’s later, an incendiary pamphlet spread throughout the area, attacking the dominant Dutch. The author bemoaned that out of loyalty to the colony, Dutch bosses strategically rallied votes for their own slates of candidates. The author complained bitterly: “We do not want to live where wooden-headed and wooden shod have absolute control of public affairs, where the people are a hundred years behind the time… We want to live in a community controlled by public spirited, progressive men—men who are abreast with the century.”[3] The pamphlet went further to describe the immigrants as “clannish” and to accuse them of making every effort to “hinder and prevent their enlightenment.”[4] Immediately following the election, which the Dutch candidates won handedly, a immigrant-owned paper printed the entire pamphlet and thanked the author for motivating the community to “rise in their might” and “crush the [non-Dutch ticket] beneath their feet, killing it so completely that there is no hope of its ever reviving.”[5] The foundational political distinction that shaped this region’s early days distinguished people into two primary groups: the Dutch and the non-Dutch.

To be clear, a direct line cannot be traced from the early Dutch identity and political formation in this region and Tuesday’s election results, yet historians like Michael Douma and Robert P. Swierenga have done excellent studies demonstrating that although these loyalties became more muted in the twentieth century, they did not disappear. On Tuesday, ethnic identity was not the defining factor nor was it necessarily a major one; however, the history of the region’s political and ethnic identity suggests that in one way or another it played at least a small role.

Some major changes in identity and how these communities think about loyalty to one another are evident in the increasing loyalty to party over ethnicity. In the 1870s and 1880s, immigrant voters split their tickets between parties frequently in order to cast their ballots for fellow immigrants and their second-generation children.[6] That isn’t the case anymore. Two years ago ethnicity wasn’t enough to woo many Dutch-American Republican voters toward Democrat J.D. Scholten—whose last name, like Feenstra’s, announces his Dutch bona fides. Scholten lost the same four counties by an average of over 40 points.

What the national press misses about King’s defeat is the deep history of ethnic loyalty and identity in this region. Feenstra won these four heavily Dutch counties by 8,213 votes, but he only won the primary by 7,820. I’m a historian and not a political scientist. I’ll leave that analysis to others. But the history of this region reveals that ethnic identity can clearly mark someone as an insider in the Dutch community, and insider status matters. Given Feenstra’s margin of victory and his exceptionally strong showing in proudly Dutch communities, in a small way, the history of Dutch loyalty to one another may have written another chapter in Tuesday’s primary.

[1] See, for instance, Robert Swierenga’s Faith and Family: Dutch Immigration and Settlement in the United States, 1820-1920 (New York: Holmes & Meier, 2000) or Michael Douma’s How Dutch Americans Stayed Dutch: An Historical Perspective on Ethnic Identities (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2014)

[2] “Ons County Ticket,” De Volksvriend, November 2, 1876. Formatting original.

[3] “The Free Voter,” The Sioux County Herald, November 16, 1882.

[5] “Editor’s Note,” The Sioux County Herald, November 16, 1882.

[6] See Andrew Klumpp, “Colony Before Party: The Ethnic Origins of Sioux County’s Political Tradition,” Annals of Iowa 79, no. 1 (Winter 2020): 1–35.

0