The Book

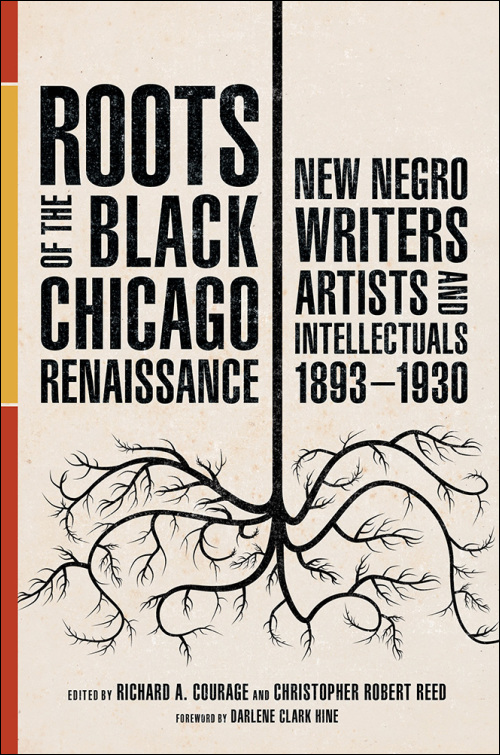

Roots of the Black Chicago Renaissance: New Negro Writers, Artists, and Intellectuals, 1893-1930. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020)

The Author(s)

Edited by Richard A. Courage and Christopher Robert Reed

Chicago’s importance to the history of Black America cannot be overstated. Whether the conversation is about activism or culture—which, often, are linked together—Chicago’s centrality in those histories can not be questioned. However, it can be debated as to when to start those conversations. Roots of the Black Chicago Renaissance: New Negro Writers, Artists, and Intellectuals, 1893-1930 makes a compelling case for starting any history of Black culture and arts in Chicago well before the traditional start date of the Chicago Renaissance in the 1930s. This collection of essays, edited by Richard A. Courage and Christopher Robert Reed, should be of special interest to intellectual historians who want to think deeply about the various influences on African American arts and letters in the twentieth century.

For Courage and Reed, one of their goals with this edited collection is “remapping African American cultural geography” (2). This book is not attempting to overturn the importance of the Harlem Renaissance or other periods of sustained African American cultural, literary, and artistic output. But Roots of the Black Chicago Renaissance does try to rethink some of those assumptions historians and literary scholars alike have made about the vibrant history of African American culture. The essays in this collection, instead, try to “describe how the cultural pioneers studied here interacted (or failed to interact) both with their fellow writers and artists in New York and with the nascent business and professional elites of the South Side” (5). Roots of the Black Chicago Renaissance asks us to reconsider the importance of geography in intellectual and literary history. Writers, journalists, and artists in Black America never worked in isolation from the problems of segregation, racism, and white supremacy. Certainly, they were never shielded from its various forms in the Deep South, the West Coast, or in Chicago. As argued later in the book, “to speak of Chicago as a hub of black cultural production is potentially less a matter of midwestern counterstatement than it is a more urgent recognition that eight hundred miles isn’t much distance in the context of a national system of Jim Crow” (95).

Something that makes Chicago unique in the history of Black art is the importance of African American patrons, who themselves built a fortune catering to the rapidly growing African American population in Chicago in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The relationship between Black art in and Black business in Chicago is always at the forefront of Roots of the Black Chicago Renaissance, as is World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. Again, these elements highlight the uniqueness of Black artistic endeavors in Chicago before the 1930s.

The various essays of this book link to specific people and moments in Chicago’s African American artistic and literary history before the Great Depression. Reflecting on the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, John McCluskey Jr. argued that the event was part “of an emerging debate as to what constituted an original American artistic expression and its various representations” (42). Considering that the World’s Fair came undo intense scrutiny and criticism from African Americans for its noticeable lack of space given to a specific African American pavilion, Douglass’s attempts to enrich the exhibitions with ideas of African civilization—especially referring back to ancient Egypt and modern Haiti—were part of the larger African American history of debating what American art could, or should look like.

An edited collection like Roots of the Black Chicago Renaissance also contributes greatly to the notion of a rich intellectual life in Chicago that will give plenty for intellectual historians to consider for years to come. For example, my favorite essay in the piece was by Richard A. Courage and James C. Hall, titled “Fenton Johnson, Literary Entrepreneurship, and the Dynamics of Class and Family.” Here, Courage and Hall remind us of how important Chicago has been to the history of African American publishing by highlighting a magazine that is not well known, Champion Magazine of Negro Achievement. While it only published for two years, Champion Magazine was on par with magazines such as the NAACP’s The Crisis or later literary journals born in Harlem during the 1920s. Champion served also as a grandfather to the future magazines published in Chicago—namely, the Ebony/Jet/Negro World/Black Digest empire of John H. Johnson that boomed in the 1960s, and has been written about extensively by historians Johnathan Fenderson and E. James West.

Throughout the book, several themes of African American intellectual history come out. First, the question behind what constitutes intellectual history comes up time and again. Authors in Roots of the Black Chicago Renaissance write extensively about the importance of dance and visual culture (both painting and photography) to the larger realm of arts and letters in Chicago. In addition, the lifting up of intellectuals such as Fannie Barrier Williams

or the various members of Chicago’s Letters Group helps us to think about whose ideas should be studied and added to the larger pantheon of American intellectual history. Ultimately, Roots of the Black Chicago Renaissance should provide plenty for intellectual historians to think about as we consider the history and relevance of African American intellectual history—to both those who are specialists in the field, and those outside of it.

About the Reviewer

Robert Greene II is an Assistant Professor of History at Claflin University, as well as blogger and Book Reviews editor for the Society of U.S. Intellectual Historians. Dr. Greene has also been published in The Washington Post, The Nation, Jacobin, In These Times, Oxford American, and other publications.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this post Robert. It happens to coincide with my reading about the life and works of Charles White (whose first wife was Elizabeth Catlett!), an artist who has long deeply intrigued me. I was delighted to learn he later settled (the year of my birth), here in California (Altadena), with his second wife Frances Barrett. White appears to have been a voracious reader (at least for an artist!), no doubt in part attributable to the fact that his hard-working mother dropped him off at the public library (de facto daycare) before going to work for the day (which is also where his incipient artistic longings first took shape). The philosopher Alain Locke, who of course earlier supported and publicized the Harlem Renaissance had some interesting things to say about the comparative differences between the earlier Harlem Renaissance and the Black Chicago Renaissance, the latter being more oriented around a politically and ethically sensitive “social realism” that was unabashedly celebratory of Black struggles and achievements in all walks of life as well as in the (natural and social) sciences, the arts, and public office.

An earlier book also relevant to this topic: Anne Meis Knupfer, The Chicago Black Renaissance and Women’s Activism (University of Illinois Press, 2006).

Thanks so much for your comment–I’m glad you mentioned Locke, because he looms over this volume in several ways. And your mention of how he distinguishes the Harlem and Chicago Renaissances comes up in the book as well.