My first social gathering since the quarantine was a meeting of our record club, which I’ve mentioned before on this blog

. We met outdoors, across a wide deck, four couples, well-separated and following recommended precautions. Each couple brought a separate speaker, and we played our selections from our phones. Our theme: what music has helped you during the pandemic?

It wouldn’t be a hard question to answer–not for me. Facing a school shut-down and a week to shift to online instruction, I happened to find myself in possession of Fela Kuti’s entire recorded catalog, a recent gift, some twenty-seven hours of music. I ripped the songs to my computer, arranged them on a playlist, and set the playlist on repeat. During what turned out to be more than a month of days spent in front of the computer, this was my soundtrack. I listened through a few times in chronological order, then a few more times through on shuffle. At some point, I started rating the songs as they came up, later sorting them according to rating so as to listen to my favorites first, and so on, in various configurations.

Fela Anikulapo Kuti was born in 1938 to a prominent Nigerian family. His father was a minister and educator, his mother an activist for women’s rights and other causes, widely respected, a real personage in her country. Fela was educated in London. He was to study medicine, like his brothers, but switched to music, strongly influenced by modern jazz, particularly Miles Davis. He formed a band with drummer Tony Allen, playing something very close to highlife, a West African genre popular since well before decolonization.

A turning point came in 1969 when a benefactor sent Fela and his band to Los Angeles. Fela was reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X and socializing with members of the Black Panther Party. He formed an intellectual and romantic relationship with party member Sandra Smith (later Izsadore). While Smith schooled him on the movement, Fela represented to Smith something authentically African at a time when many American blacks were committing to pan-Africanism, third world alliances, and a cultural return to roots. The result was a transatlantic exchange of music and ideas that would have a lasting significance.

Back in Nigeria, Fela and Allen formed a new band, Africa 70, and began to play a new kind of music, which they called afrobeat. Afrobeat retained components of highlife but also incorporated percussive and chant elements of traditional African styles as well as the various currents of postwar jazz. Lyrics were sung mainly in pigeon English, which made them more accessible across the continent and signaled a consciousness of social class. Critical, too, was the influence of James Brown–as an innovator, a bandleader, and a personality. Fela had followed Brown’s music for some years, but he also may have seen Brown and his band play live during his American sojourn.

A live recording of Brown that year in Augusta, Georgia, offers an idea of what Fela would have heard. Having established a new genre of his own–“a brand-new bag,” today called funk–Brown led a crack band of some fourteen members, including three drummers, and a road crew, staff, and entourage of similar size. The James Brown Orchestra crisscrossed the country, slaying auditoriums nightly, playing their vamp-based songs at breakneck tempos, making a sound never before heard. Importantly, too, as an influence on Fela, was James Brown’s August 1968 hit, “Say It Loud–I’m Black and I’m Proud.” The political element in Brown’s music would be fairly short-lived. For Fela, the merger of politics and music endured.

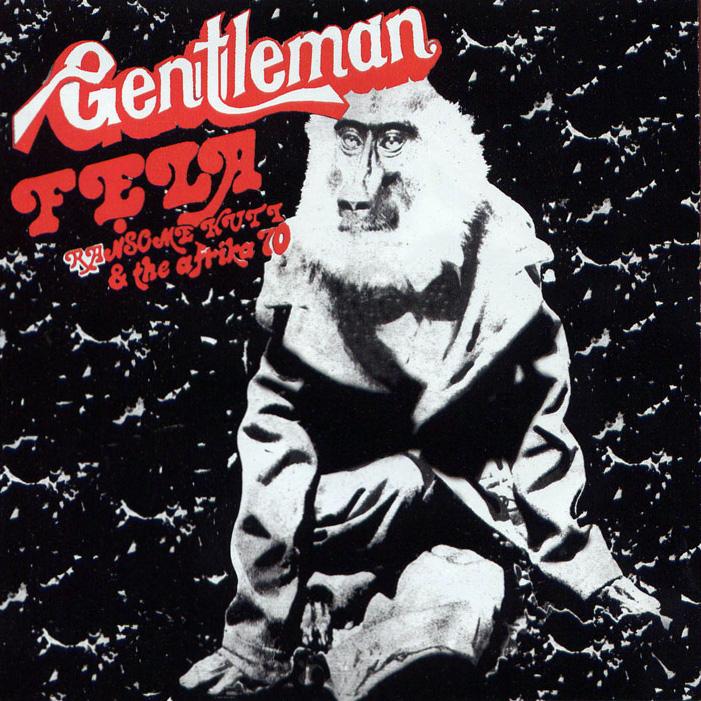

“Gentleman,” “Water Get No Enemy,” “Go Slow”: as the weeks went by, my favorites list from the discography grew. Choosing which one to play for the record club was mainly a problem of length. The whole concept of the club, in which we went around the circle, each person taking a turn, was built on the tacit understanding that a three- or four-minute song was the norm. A Fela cut, in contrast, tends to run up toward twenty minutes. Typically, it will begin with a slow build-up of instruments– guitar, bass, second guitar, percussionists–vamping on a one- or two-measure rhythmic pattern. Then comes a series of jazz choruses, improvised solos by saxophone or keyboard, intercut with R&B-style melodic heads played by a full horn section. At about the halfway mark, recognizable verses begin, and then vocal choruses, a call-and-response between Fela and the back-up singers. Now fully mature, the song serves its teaching function, and Fela delivers his political and social commentary.

“Gentleman,” “Water Get No Enemy,” “Go Slow”: as the weeks went by, my favorites list from the discography grew. Choosing which one to play for the record club was mainly a problem of length. The whole concept of the club, in which we went around the circle, each person taking a turn, was built on the tacit understanding that a three- or four-minute song was the norm. A Fela cut, in contrast, tends to run up toward twenty minutes. Typically, it will begin with a slow build-up of instruments– guitar, bass, second guitar, percussionists–vamping on a one- or two-measure rhythmic pattern. Then comes a series of jazz choruses, improvised solos by saxophone or keyboard, intercut with R&B-style melodic heads played by a full horn section. At about the halfway mark, recognizable verses begin, and then vocal choruses, a call-and-response between Fela and the back-up singers. Now fully mature, the song serves its teaching function, and Fela delivers his political and social commentary.

Maybe it was merely coincidental that a) the virus had sentenced me to long hours at the computer, and b) I had this enormous body of music available to consume. Maybe that was just a happy opportunity. On the other hand, when the workday was over, after I’d taken in a painful dose of the evening news, after dinner was finished and the dishes done, it was my handful of Fela vinyls, procured back in the 1980s, that invariably found their way to the turntable. I’d been obsessed with artists before. This was different. This was more a kind of therapy. I began to wonder if there wasn’t something particular that this music supplied that met what the moment required.

Fela’s lyrics showed him to be in rebellion not only against the emotional and structural legacies of imperialism but also against Nigeria’s post-colonial, military government, awash in petro-dollars. Fela, his large band, his dancers, his family–which included numerous wives–and the many others associated with his organization, lived on a compound in a poor section of Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city. The compound included living spaces, a studio, a nearby performance hall, and a health clinic that served the neighborhood. Dress was casual, herb-smoking a daily ritual. Fela named his commune the Kalakuta Republic, after a jailhouse where he’d been incarcerated, and declared it to be an independent state, outside the jurisdiction of the authorities.

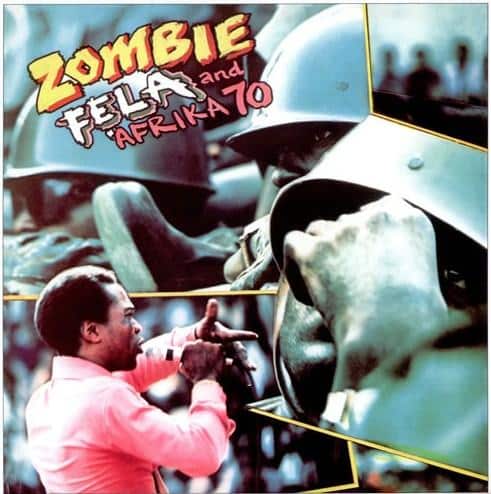

“The government regarded Kalakuta as an affront,” scholar Randall Grass writes, “a first step toward incipient, secessionist anarchy, no joke in a country racked by civil war.” Fela seemed to like nothing better than to taunt the junta and its leader, General Olusegan Obasanjo. His massive 1976 hit, “Zombie,” depicted Obasanjo’s troops as mindless automatons. In February of 1977, soldiers and police invaded the compound. Inhabitants were beaten, raped. The buildings were set afire. Instruments and masters tapes were destroyed. Fela was beaten almost to death, and his mother, the famous activist then in her late seventies, was thrown from a window. She died from her injuries the following year.

“The government regarded Kalakuta as an affront,” scholar Randall Grass writes, “a first step toward incipient, secessionist anarchy, no joke in a country racked by civil war.” Fela seemed to like nothing better than to taunt the junta and its leader, General Olusegan Obasanjo. His massive 1976 hit, “Zombie,” depicted Obasanjo’s troops as mindless automatons. In February of 1977, soldiers and police invaded the compound. Inhabitants were beaten, raped. The buildings were set afire. Instruments and masters tapes were destroyed. Fela was beaten almost to death, and his mother, the famous activist then in her late seventies, was thrown from a window. She died from her injuries the following year.

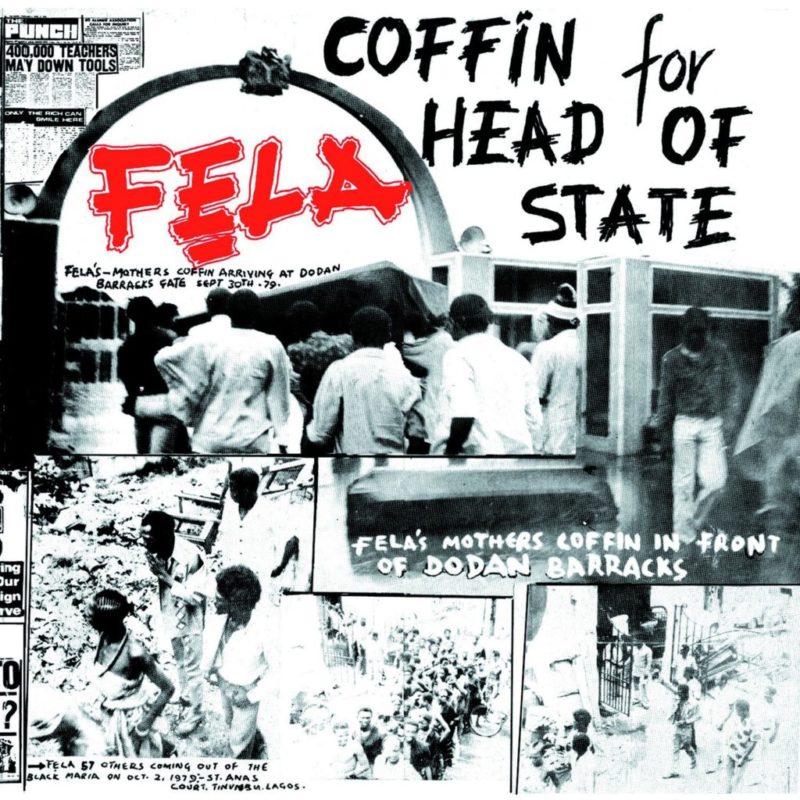

The effects of this assault on Fela should not be underestimated. He redoubled his resistance against Obasanjo. Numerous recordings addressed the attack head-on: “Unknown Soldier,” “Sorrow, Tears, and Blood.” Fela used music to process his trauma, though no music could have completely healed the physical and psychic wounds. In the new commune Fela established to replace Kalakuta, he put a coffin on the roof to memorialize his mother’s martyrdom. He began to speak regularly of receiving communications from her spirit.

The attack may have also encouraged an already stout megalomania. As did two other domineering, genre-inventing band leaders–I’m thinking not only of James Brown but also Bill Monroe–Fela faced rebellions and ultimatums within his own camp. Tony Allen left in 1979 and took many of Africa 70 with him. Fela brought in new talent, renamed the band, and continued to record for almost two decades, until his death from AIDS in 1997.

One of Africa 70’s last recordings, made during a transitional period following Allen’s departure, was “Coffin for Head of State” (1981). The record and its cover art recount General Obasanjo’s last day in office. A civilian government had been voted in. Fela removed his mother’s coffin from the rooftop display and carried it in a procession to Dodan Barracks, the General’s quarters. There he deposited the coffin as a final protest and reminder of the brutality of his loss.

One of Africa 70’s last recordings, made during a transitional period following Allen’s departure, was “Coffin for Head of State” (1981). The record and its cover art recount General Obasanjo’s last day in office. A civilian government had been voted in. Fela removed his mother’s coffin from the rooftop display and carried it in a procession to Dodan Barracks, the General’s quarters. There he deposited the coffin as a final protest and reminder of the brutality of his loss.

The song starts, as usual, with interlocking bass and guitar figures. Fela plays a few stately chords on electric piano. The groove builds and releases, builds and releases, breaking down again and again to its initial, two-measure vamp. The lyrics are gospel-like when they finally kick in. “Almighty Christ our Lord,” Fela sings; “Amen, amen, amen,” the singers chant. Yet Fela wants to denounce Christianity–and Islam, too–as illegitimate imports, hypocritical covers for corrupt power. He mockingly imitates the sound of Latin and Arabic prayers. Then he’s walking, describing a journey across Africa.

I waka waka waka

I go many places

I see my people

Them dey cry cry cry

He notes the hurts, the abuses. General observations become personal ones.

Them steal all the money

Them kill many students

Them burn many houses

Them burn my house too

Them kill my mama

So I carry the coffin

I waka waka waka

“Coffin for Head of State” clocks in at almost twenty-three minutes. As with all great Fela songs, uncompromising sentiments are delivered inside a deeply soothing, hypnotic groove. “Ain’t it good to ya?” James Brown would say about music like this. As I’ve lived this pandemic, and as I’ve watched how our highest leadership has responded, its seemingly eager sacrifice of the weak, the disadvantaged, and the old to self-interest, Fela Kuti’s music served as an anodyne without diluting the anger, while leaving contempt intact.

_________

Both a recent documentary on Fela called Finding Fela! and another from 1982 called Music is the Weapon are available to stream from Kanopy and other services.

Randal F. Grass writes about Fela in The Drama Review, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1145717?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Sandra Izsadore remembers Fela in the LA Weekly: https://www.laweekly.com/fela-kutis-lover-and-mentor-sandra-smith-talks-about-afrobeats-l-a-origins-as-fela-musical-arrives-at-the-ahmanson/

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Good stuff. Love your music reflections here.

Your first para transported me back to the 1970s—carrying speakers to a gathering.

No one had introduced me to Fela Kuti until now. So now I’m listening, and enjoying, to the music on Spotify. The first song that arose was “Water No Get Enemy.” I hear the jazz, obviously, but also the blues. Not as much funk, but it’s there lurking—in this one song. And yes, at 9:51, this is a groove, a tune for drinks. I feel the herb-smoking, drifting in the background.

Next is “Zombie,” which I’m sure I’ll enjoy. …Consider this comment an appreciation. Thanks for the introduction, yet again, to some new music for me. – TL