The Book

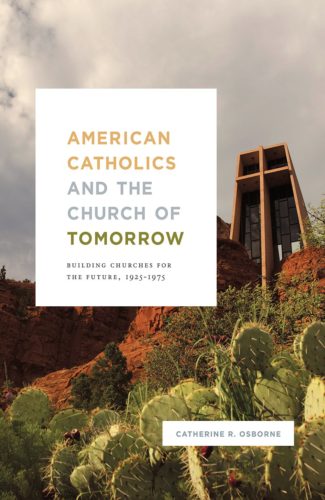

American Catholics and the Church of Tomorrow: Building Churches for the Future, 1925-1975. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

The Author(s)

Catherine Osborne

Catherine Osborne’s American Catholics and the Church of Tomorrow

is a compelling, beautiful history of twentieth-century Catholic liturgy and architecture. Compelling because of her extensive research in the archives and published sources. Beautiful because of her talents as a stylist, as well as the University of Chicago Press’s decision to include, by my count, sixty-five black-and-white pictures. In the book, Osborne traces how a coterie of liturgists and architects—who she terms Catholic modernists—came to embrace evolutionary thinking and modernist aesthetics in the twentieth century. Laying aside the old rubrics, this group set about sketching and modeling churches that would meet the spiritual needs of present and future Catholics, not resurrect Gothic and Baroque styles. Their designs sought to promote lay participation in the mass, to break down barriers between the church and society, and, ultimately, contribute to the world’s final redemption. But, for some of these Catholic modernists, these aesthetic and theological ideas primed them not only to re-imagine sacred space but also to challenge the very notion of the sacred after the Second Vatican Council.

This process began in the early twentieth century when a cohort of young architects traded in traditionalist assumptions for modernist principles. At the fin-de-siècle, neohistoricism dominated Catholic church design. Its practitioners believed that the old masters had developed a set of religious architectural forms, and that good design amounted to deft combinations of these forms (8). In the decades after the First World War, however, a crop of young Catholic artists rejected such notions. Drawing upon evolutionary and architectural discourses—with some studying under Frank Lloyd Wright, like Barry Byrne—Catholic modernist architects adopted a “biological paradigm” in which adaptation was central (6). And their designs were not only adapted to climate and landscape but also to the needs of the specific parishes in the twentieth century. Thus, they adopted a more dynamic, evolutionary approach to liturgy and architecture.

While Pius X had censored the theological modernism in his 1907 encyclical Pascendi Dominici Gregis, the aesthetic expression of similar ideas proved less incendiary, or perhaps was less closely monitored, in artistic forums like the magazine Liturgical Arts.

Their embrace of evolution, as a theological as well as aesthetic principle, manifested itself in the models they constructed and the materials they selected. While financial constraints and skeptical constituencies limited the number of projects Catholic modernists could pursue, paper architecture offered a space to construct an idealized, if not quite realizable, future. In their designs, they imagined new trajectories for the churches of tomorrow, which often featured cutting-edge materials and techniques. And occasionally, circumstances allowed for the execution of these projects, including the Chapel of the Holy Cross in Sedona, Arizona, the Church of St. Mary and St. Louis in Creve Coeur, Missouri, and St. Patrick’s in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. This embrace of glass walls and reinforced concrete, Osborne argues, was informed not just by professional training but also by theological beliefs. They considered twentieth-century materials no less redeemed than the stone composing medieval cathedrals, and they believed these materials lent themselves to more modern liturgical design and sacred space. The load-bearing capacities of concrete eliminated the columns that often separated congregants from each other and from the altar; the transparency of glass walls illuminated sacred spaces and connected it to the outside world; the simplicity of concrete and glass would not distract parishioners during the mass. In short, modernist design worked in hand with liturgical goals to bring together priest and congregation, the church and world around it.

Furthermore, Osborne argues, modernists envisioned the churches of tomorrow as extending Christ’s presence in the world and helping bring about the world’s final redemption. Their embrace of evolutionary biology primed these Catholics to embrace a progressive theology that looked forward to the eschaton. So when translations of the French Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin began to appear in 1959, modernists found a theological touchstone they had long lacked. Particularly attractive was his idea that the world was progressing from biosphere to noosphere, a period, to quote Osborne, “where thinking human beings would develop a unified network of thought and spirit” (120). Modernists understood themselves as contributing to an increasingly connected and extended “network of thought and spirit” when they sketched plans for ecumenical submarines and lunar chapels—and when they augmented religious experience with drugs.

But in the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), modernists found the imprimatur for the architectural and liturgical experimentation they had long desired yet rarely enacted. Documents such as the pastoral constitution Gaudium et spes encouraged Catholics, clergy and laity alike, to engage more positively with the world. Catholic modernists, for their part, strove to integrate the church into its urban and suburban environments. They tried to extend the church’s presence in the world by holding house masses, by building chapels in malls and beside skyscrapers. Still others attempted to break down barriers between church and city. Indeed, the glass walls of San Francisco’s cathedral, St. Mary of the Assumption, reflected the belief that the church was part of, not set apart from, the modern world. In the same spirit of blurring boundaries, liturgists and architects drafted plans for ecumenical spaces. Designs were drawn up for a Kansas City multi-denominational complex with space for Presbyterians, Catholics, Episcopalians, and the United Church of Christ. Wilde Lake’s Interfaith Center, a similar experiment in Columbia, Maryland, housed Protestant and Catholic chapels separated only by a removeable wall.

Amidst all this change, American Catholics underwent a “spatial crisis” as they reckoned with what a church even was (183). This was, at one level, due to the renovations of existing churches: the rearrangement of seating, removal of communion rails high altars, and replacement of artwork. Congregations were left wondering whether these changes were final or the first of many. But bolder liturgical experiments—floating parishes that held services in various locations and churches that converted to multi-purpose community centers—challenged more fundamental assumptions. Should churches be solely dedicated to religious activities? For decades, Catholic modernists had blurred the boundaries between sacred and secular. No wonder, then, that some of them came to question the very notion of a church building.

But how many American Catholics embraced aesthetic modernism or questioned basic premises about the nature of churches? The book’s case studies demonstrate that modernist principles inflected some architectural and liturgical discourses, but they give little sense of these figures’ influence or representativeness. Some readers may also question Osborne’s readiness to attribute theological motivation to her subjects, though she certainly does demonstrate the veracity of these beliefs in many instances. Perhaps some architects, especially those who were not Catholic, adopted religious language merely to pitch their projects. And perhaps some priests found these designs favorable for more pragmatic reasons: low costs and quick construction.

But if American Catholics and the Church of Tomorrow provokes questions, it also suggests that answering these questions has importance for our understanding twentieth-century US history. For intellectual historians in particular, Osborne reminds us to pay attention to scientific, aesthetic, and theological ideas helped shape the sacred and secular spaces of the twentieth-century United States.

About the Reviewer

David Roach is a PhD candidate at Baylor University in the history department.

0