Editor's Note

“I’m excited about any kind of intellectual history that has explanatory power.”—Sarah Bridger

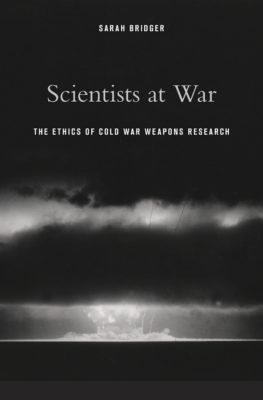

Hope you’re enjoying our weeklong conversation with past prize winners! Catch up on the Spotlight/Insight series here, here, and here. We chatted with Sarah Bridger, associate professor of history at California Polytechnic State University and Daniel Immerwahr, associate professor of history at Northwestern University, who won the 2016 USIH Book Prize. Check out Bridger’s Scientists at War: The Ethics of Cold War Weapons Research. Plus! Enter YOUR book for our annual prize. Entries are due 15 April 2020

Hope you’re enjoying our weeklong conversation with past prize winners! Catch up on the Spotlight/Insight series here, here, and here. We chatted with Sarah Bridger, associate professor of history at California Polytechnic State University and Daniel Immerwahr, associate professor of history at Northwestern University, who won the 2016 USIH Book Prize. Check out Bridger’s Scientists at War: The Ethics of Cold War Weapons Research. Plus! Enter YOUR book for our annual prize. Entries are due 15 April 2020

and you can find all the submission details here.

What are you working on now?

Sarah Bridger: My current research explores shifting ideas in the United States about what counts as science and who counts a scientist…and the wider implications of differing answers to those questions. I’m particularly interested in the intense political, economic, and ideological battles of the 1970s: changes in research priorities and intellectual property rights, theoretical critiques of scientific practice, the activism of women in STEM fields, and the rise of citizen science. This project actually started as a very small exploration of women in mathematics in the 1970s, expanded to sprawling multidisciplinary dimensions during a fantastic sabbatical year, and now I think I’ve corralled things a bit to focus mostly on biology, broadly defined. The tentative title is Life as We Know It: Biologists and the Remaking of Science and Society in the 1970s. But the women mathematicians are still in there, alongside Black Panther biochemists, biotech entrepreneurs, antinuclear activists, social constructivists, and many others.

Within our field of intellectual history, what topics or approaches are you excited about?

Within our field of intellectual history, what topics or approaches are you excited about?

Bridger:

It’s hard for me not to be extremely presentist in our current moment. I’m excited about any kind of intellectual history that has explanatory power. Some of my favorite books in the past few years have been works of political economy. There’s been a wave of innovative approaches to tracing how the mix of ideology, politics, and material concerns have fueled the war on crime, shaped the character of current news media, enabled the transition from New Deal liberalism to neoliberalism, deepened the economic crises of the 1970s, etc. It’s inspiring.

This year, our annual meeting theme is “Revolution and Reform.” Can you reflect on how those ideas connect to your scholarship?

Bridger: My book Scientists at War examined competing ideas among Cold War scientists about how best to influence policy: whether to work inside or outside the system, or—by the time of the Vietnam War—whether to try to destroy the system itself. I tend to be attracted to the study of competing visions of politics, economics, and ethics in times of social upheaval, so “Revolution and Reform” connects very closely to my own scholarly interests.

0