The Book

Humanitarian Photography: A History. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015, 345p.

The Author(s)

Heide Fehrenbach and Davide Rodogno, editors.

The relative newness of the term “humanitarian photography” is indicated in its absence in two widely used historical surveys of photography, Beaumont Newhall’s History of Photography (1982) and Naomi Rosenblum’s A World History of Photography

(1984). Nor does the term found in the work of Vicki Goldberg, Susan Sontag, Susie Linfield, or Ariella Azoulay, four of the most important late-twentieth-century critics writing on photojournalism. Heide Fehrenbach and Davide Rodogno, the editors of Humanitarian Photography: A History, state in their introduction that the concept of “humanitarian photography” first arose in the 1990s, originated by historians of human rights, philanthropy, and humanitarian aid as they began analyzing the use of photographs to document and publicize humanitarian causes. The twelve essays in Fehrenbach and Rodogno’s book examine the relationship of photography and humanitarianism since the 1870s. Indeed, photographs offer a particularly rich source for narrating the history of humanitarianism and humanitarian aid as intimately connected over the last 150 years. Relief organizations produced most of the photographs shown in the book. They wanted to document their work, and, by providing the public with images that appealed to their Christian sentiments and/or feelings of civic responsibility, they hoped to expand support for their activities.

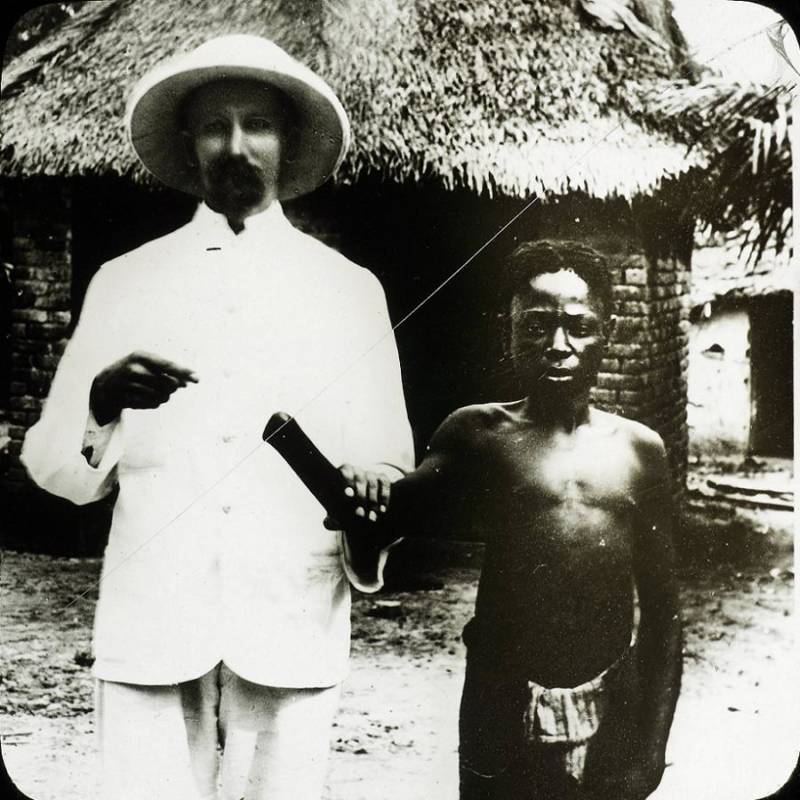

The most important contribution of this volume is the development of a new historically useful concept with ramifications for the history of photography and, more broadly, for the visual history of the contemporary world. The chapters in the book are organized chronologically rather than thematically, giving readers a complex sociological and historical account of the “politically and morally charged terrain” (p. 6) surrounding the use of photography to stimulate international interest in humanitarian causes. The chronology reveals three major phases to the production and publication of photographs of conflicts, wars, and humanitarian emergencies. The earliest pattern involved producing visually compelling images that demanded a reaction by appealing to the public’s religious sentiments. In the first chapter, Heather D. Curtis examines the use of photographs to support humanitarian interests in two Christian newspapers published in the United States in the nineteenth century, the Christian Herald and the Missionary Alliance. Curtis shows that photographs often produced contradictory reactions. While some readers saw the images promoting empathy with those who were suffering, others protested that overly dramatic images of people in stress did not produce solidarity but a hierarchy of experience separating “we Christians and the other.” With the aim of clarifying the complex relationship between atrocity, photography, and humanitarianism, Christina Twomey’s chapter analyzes three case studies of late nineteenth-century photographs documenting atrocities perpetrated in Bulgaria, India, and the Congo. Twomey highlights the gradual politicization of humanitarian attitudes, the relationship between text and image in depictions of atrocity in newspapers, the ways in which photography stimulated within the public distinctions between “we and the others.” Kevin Grant’s chapter explores the photography that Christian missionaries in the Congo produced of atrocities in the country under the personal rule of King Leopold of Belgium. Grant focuses on missionary Alice Harris, whose photographs reflected and reshaped her understanding of humanitarian commitment. Grant then examines the use of missionary photographs from the Congo at conferences, magic lantern exhibitions, as well as illustrations for newspaper articles, while noting how each venue had different but strict limits on what could be shown. Peter Balakian’s chapter evaluates photographs of the Armenian Genocide that Near East Relief produced in the 1910s, work that emphasized the Christian identity of the Armenian people and the salvationist values motivating aid from the United States.

MISSIONARY WITH ATROCITY VICTIM IN BELGIAN CONGO, LATE 19TH CENTURY

The transition from religious to civic appeals is the subject of the next two chapters. Heide Fehrenbach focuses on the representation of children at risk used in three distinct “Save the Children” campaigns, the postwar famines of the early 1920s, the Spanish Civil War, and the Second World War. Caroline Reeves and Francesca Pina contributed two chapters that both examine how during the First World War, the Red Cross developed new approaches for the photographic depiction of the vulnerable, preferring images shift emphasis away from victims and their suffering to highlight the effective modern efficiency of Red Cross staff providing aid and rescue. Both authors argue that the work of the Red Cross during the war dramatically transformed humanitarian activity in conflict situations, including the visual repertoires for how relief work was presented to the public.

RED CROSS WORK WORLD WAR I

The next four chapters evaluate the new standards for humanitarian work and its documentation that prevailed over the next fifty years as international organizations grew in importance to relief efforts. Silvia Salvatici examines the photographs that the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), created in 1943, produced to publicize European reconstruction efforts. Salvatici emphasizes the close working relationship UNRRA had with the administration of President Franklin Roosevelt. The goal of consolidating an international coalition of U.S.-led liberal democracies reconfigured what photographers recorded as well as how and where humanitarian photographs were distributed. Davide Rodogno and Thomas David explore similar issues in their analysis of the visual politics of the World Health Organization, created in 1948 to replace both the UNRRA and the League of Nations Health Organization. The chapter focuses on the early years of the World Health Organization, when the new agency favored strongly paternalistic discourse, using photographs to identify what they argued was necessary to promote good health and to condemn alternative practices as opposed to progress. Chapters by Lasse Heerten and Henrietta Lidch examine atrocity photographs from the 1970s. Heerten focuses on the Biafran war, and Lidchi on the Ethiopian famine. In both crises, international aid organizations created photographic events featuring sympathetic portraits of the victims to mobilize public support for their work. The two chapters stress that in both African crises the relationship of memory and ethics became an central subject for discussion, a development that contributed to rethinking the presentation of suffering and aid work, while leading to the formulation of “humanitarian photography” as a formalized topic of study in the last decade of the century.

ETHIOPIAN FAMINE 1985

The concluding chapter by Sanna Nissinen summarizes historical dilemmas found across 150 years of efforts to use photographs to publicize and promote humanitarian causes, arguing that, “Polarizing humanitarian photographic practice into positive/negative and ethical/unethical limits the potential and opportunities of the medium. Such potential may best be realized by reinserting a consideration of social lives that occur outside the frame in our view of the photograph” (318). By the end of the volume, readers will have gained a thorough historical overview of a distinct photographic practice, with case studies from Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and the United States. Latin America is the only section of the world ignored. Subsequent work on the topic of humanitarian photography should include case studies from Latin America, where indeed the connections between humanist and humanitarian photography have long been particularly porous.

About the Reviewer

Ana Maria Mauad is Professor of History at the Universidade Federal Fluminense (Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro), where she is a leading member of the Laboratory for Oral History and the History of the Image. She is the author of Poses e flagrantes: Ensaios sobre História e Fotografias (“Snapshots and Posed Takes: Essays on History and Photography”) as well as many essays on the work of a wide range of nineteenth- and twentieth-century photographers, including Salvador Salgadão, Milton Guram, Cláudia Andújar, and Genevieve Naylor.

0