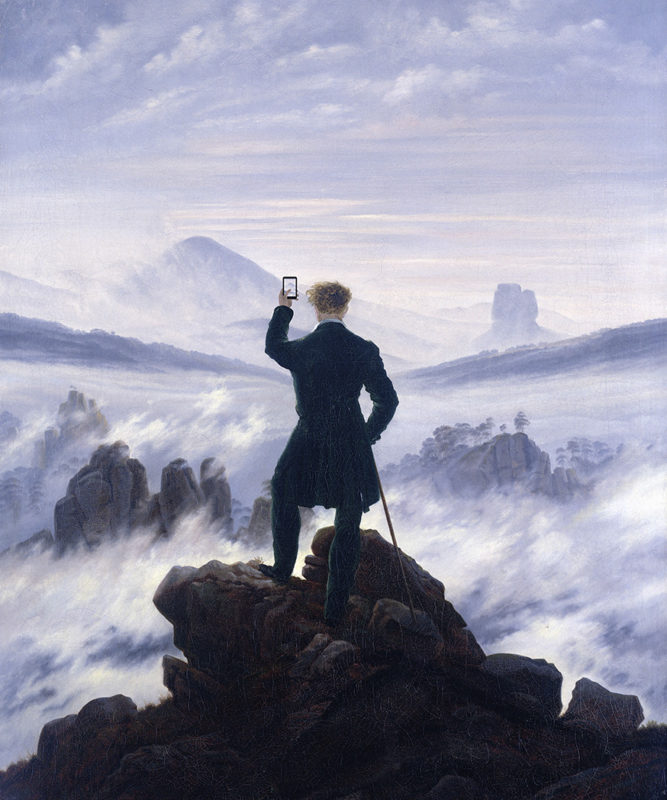

“When you see the amazing sight,” ART X SMART Project by Kim Dong-kyu, 2013. Based on: “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog,” by Caspar David Friedrich (1818).

Recent debates over monuments, miniseries, and manuscripts—in print and online—have reminded us that public interest in the American past continues to be a vibrant flashpoint of discussion. But who is that digital public? And why should we, as historians, seek to connect? Contests over what constitutes a sacred battlefield, who the founders really were, when to tweet about politics, or how we string together the quintessentially “American” moments that make a good textbook or a dynamic survey course, have invited new perspectives on how historians work, and what their role should be in the digital public square. At the same time, the rise of new media—in the form of websites, blogs, and podcasts—has radically changed storytelling opportunities and professional paths for historians. Multimedia narratives, too, offer new ways to interpret primary sources and to present historiography for a “general audience.” How does the American digital public, in turn, change our scholarship and related cultural institutions?

These themes struck me, especially, at the #USIH2019 meeting in New York, as I watched historians engage with new forms of media. And it made me think 1) related ideas welcome for #USIH2020 in Boston! plus 2) with the decade waning to days, what is the intellectual history of the digital public thus far? Lots of questions here already, but let me add a few more (hey, it’s an open thread). Historians, let’s chat about audience. Whether phenomenon or phantom limb, technology gives us chances for documentation, collaboration, and—as Cathy N. Davidson and other scholars have shown—the chaos of attention blindess. What diverse strategies do we use to convey long-format history through new media? For, thanks to the digitization of primary sources and to venues like Twitter that circulate academic research far beyond traditional channels, professional interest in democratizing the archive has shifted to a new goal: broadening engagement with complex historical narratives. When do we “make” digital publics to debate the American past, and (why) should we pay attention to them? Share your thoughts in the comments!

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Sara — Great prompts about the “American digital public”! I have a few points to start off the thread. I’ll break them down by the three words you use.

(1) American: It might be worth considering how the current configuration of the digital intensifies long-running changes in community shaped by technologies of communication. What exactly is the local, the national, and the international when the digital fosters so many new connections (or disconnections!) across these arrangements of space. Who gets to be American in this new techno-communicative space? What does it even mean to be American (or not American) in the digital space?

(2) Digital: Of course behind the issue of community boundaries local, national, or transnational is the question of how much we are imposing onto digital platforms and how much they are technologically determining our new social interactions. I think one important issue is to query the nature of the digital platforms themselves: who owns them? What happens to the data we generate on them? What are their rules and protocols? It seems to me that as public historians, we have lots to learn from the media studies folks (Galloway, Chun, Manovich, Gitelman, Noble, many many more) about the material underpinnings of the digital public square, of the commons. We also have lots to learn from the media archeology theorists who have been considering the nature of the digital archive (thinking of Ernst, Kittler, but also, of course, the many scholars who have taken up their approach to the digital archive, which is framed often as a kind of Foucaudean genealogy/archeology challenge to history as they understand it to be practiced.

(3) Public. I think we could also turn back to public sphere theory in thinking about the digital present. Is there, was there, ever such a thing as the much-idealized unitary public sphere? Has the idea of a public square itself often been wielded normatively to exclude voices as much as include them? How much is a public a market or not? Which is to say, how does it relate to a market (so much contemporary hand-wringing among historians about the public and the general audience really conflates public with audience of reading consumers—and problematically so I think)? Is there an American digital public or are there American digital publics? Does it matter? Are those the same as the “media bubbles” everyone talks about these days or are there other ways of considering an American public life that is multifacets rather than unified? Do we want a Habermasian public of rational-critical debate or an agonistic public a la Mouffe/Laclau or a phantom public as Lippmann imagined or a Great Community as Dewey hoped when it goes digital?

OK, I’ve merely raised more questions here in response to your questions and maybe gotten way too theoretical and abstract. Maybe as the conversation develops we can try to come up with more concrete examples as well as more developed theories, interpretations. Maybe even some answers!

I have other thoughts about how the techniques of historical analysis might provide a model for the American public sphere you describe so that it’s not just historical content, but also the sharing of historical method that serves the larger goal of a thriving, just, democratic public life, but I’ll leave that for later.

Thanks for starting this conversation.

— Michael