Here it is, just over a week left in the semester, and I’m still trying to process the reading I did last summer. I read science and social science, history and novels, biography and memoir. Despite this variety, much of what I read seemed to converge on the same topic—our present crisis, frightening to contemplate—and to arrive at some of the same conclusions. Part of my processing involves gauging how much of this convergence actually happened in the books and how much of it happened inside my own head.

Here’s one of those points of convergence: Old ideas will not be sufficient to meet the enormous challenges we face. We require an alternative paradigm, a new framework, a reorientation, a new mindset. The writers don’t use the same term. That isn’t important. What’s striking to me, as a historian of ideas, is the faith commitment that the use of these terms indicates to the causal power of ideas. To change our conditions, we must change our mental models. Those models are made of ideas.

In the preface to his book, Big World, Small Planet: Abundance within Planetary Boundaries (2015), sustainability scientist Johan Rockström writes about the presentation he and colleagues made to the 2009 climate summit in Copenhagen and how disappointed they were in the response. They’d relied on data, on factual information. It wasn’t that their audience didn’t believe in the numbers or the material realities the numbers represented. “A deep mind-shift was required for genuine change,” Rockström realized, “and that couldn’t come from numbers alone.” [1]

It’s a two-part process, really. Old ideas have to be rejected, and new ideas substituted. Moreover, in the case of mindsets or worldviews, it isn’t merely a matter of words but of deeply-set habits of thinking. These are constituted in basic metaphors, in mythological material, or sometimes in simple visual representations. George Lakoff has long explored the former. In her 2017 book, Doughnut Economics: 7 Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, Kate Raworth focuses on the latter. Change the picture, change the mind. The picture she offers is the doughnut.

I’ll get to the doughnut shortly, but I need to retrace my steps just a little. Raworth’s book was one of my summer reads. She’s an economist, not a historian, yet twelve pages in her first chapter provided one of the most satisfying histories of thought I’ve read in quite some time. It’s a history of what people meant by the word “economics,” how those who study economics came to define their discipline, and the consequences of these meanings and definitions.

I’ll get to the doughnut shortly, but I need to retrace my steps just a little. Raworth’s book was one of my summer reads. She’s an economist, not a historian, yet twelve pages in her first chapter provided one of the most satisfying histories of thought I’ve read in quite some time. It’s a history of what people meant by the word “economics,” how those who study economics came to define their discipline, and the consequences of these meanings and definitions.

Economics was a term that went back to the Greeks. It meant the art of managing the household. In the 18th century, however, the art of economics became the science of economics. The notion of art—in the sense of a subjective, purposeful, well-designed practice—was replaced by an effort to discover the purely objective “economic laws of motion.”

The trend, away from naming goals and toward discovering laws, continued in stages through the Enlightenment and the nineteenth century. By the early twentieth century, according to the standard textbook, economics was defined as “the study of how society manages its scarce resources,” but the purpose of such management had ceased to be a topic of consideration. “Today economists and politicians,” Raworth writes

debate with confident ease in the name of economic efficiency, productivity, and growth—as if those values were self-explanatory—while hesitating to speak of justice, fairness, and rights. Talking about values and goals is a lost art waiting to be revived. [2]

There’s a plug for the Humanities if I’ve ever heard one.

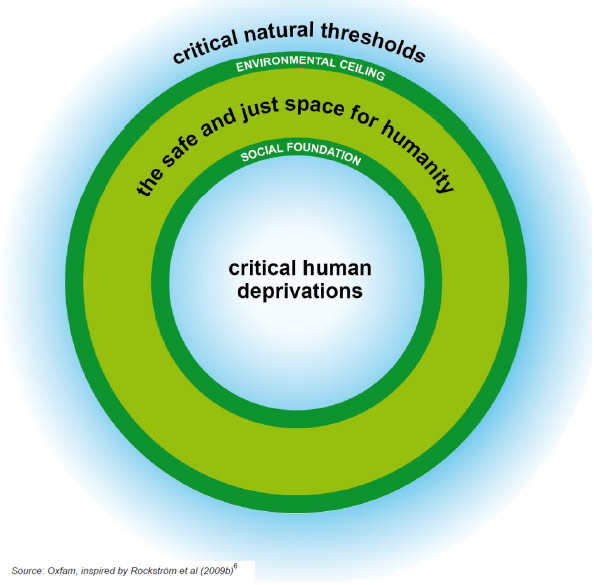

“Economics, it turns out, is not a matter of discovering laws,” Raworth sums up. “It is essentially a matter of design.” The doughnut of Doughnut Economics is Raworth’s effort to redefine the discipline by incorporating, once again, a set of values and goals. [3]

So what does she mean by the doughnut? Picture a simple drawing, a circle within a circle. The circumference of the outer circle represents the ecological ceiling of human existence, beyond which critical planetary systems degrade. The inner circle represents humanity’s social foundation. The space inside it—the empty center of the doughnut—represents the various deprivations that result when that foundation deteriorates. The possibility of human thriving, therefore, exists within the doughnut itself, the space between the inner and outer circles—under the ecological ceiling, upon the social foundation. The purpose of economics, Raworth contends, is “to bring all of humanity into that safe and just place.” [4]

So what does she mean by the doughnut? Picture a simple drawing, a circle within a circle. The circumference of the outer circle represents the ecological ceiling of human existence, beyond which critical planetary systems degrade. The inner circle represents humanity’s social foundation. The space inside it—the empty center of the doughnut—represents the various deprivations that result when that foundation deteriorates. The possibility of human thriving, therefore, exists within the doughnut itself, the space between the inner and outer circles—under the ecological ceiling, upon the social foundation. The purpose of economics, Raworth contends, is “to bring all of humanity into that safe and just place.” [4]

Will this picture do the trick? In shifting the mind, I mean. Raworth agrees, as do all the others, that we need a change in paradigm, a new economic narrative, and she believes that pictures are superior to words in effective storytelling. Certainly, her simple circle within a circle gets the point across. In the aftermath of his disappointment in Copenhagen, Rockström, whose work Raworth draws upon, also turned to visuals to reach an audience. Working with National Geographic’s Mattias Klum, he filled Big World, Small Planet with sumptuous photographs of people and nature. Apparently, the hope was that readers, drawn in by the beautiful illustrations, might look more closely at the data-driven graphs. In any case, aesthetic values needed to be paired with analytic values. “Genuine change” required “both the heart and the brain.” [5]

Of course, heart work isn’t restricted to visuals. Stories told in words can touch the heart, too. David Blight’s biography of Frederick Douglass reminded me that William Lloyd Garrison also called for “a revolution in values,” and that the antislavery movement, in general, relied on multimedia appeals. Douglass didn’t rely much on numbers—he made his audiences laugh and cry and grow angry. Does climate activism have its Frederick Douglass? Does it, for that matter, have its Uncle Tom’s Cabin?

It had been a long time since I read fiction with such excitement as I did the first half of Richard Powers’ recent novel, The Overstory. Each chapter introduced a separate character, each character without connection to the last. Yet all were somehow bound together in a thematic web that had something to do with trees. The result was a spooky kind of verisimilitude I had never experienced in fiction. The more conventional second half, in which the author brings these characters together, was therefore something of a letdown. They become a motley band of militant environmentalists—much more familiar territory.

It had been a long time since I read fiction with such excitement as I did the first half of Richard Powers’ recent novel, The Overstory. Each chapter introduced a separate character, each character without connection to the last. Yet all were somehow bound together in a thematic web that had something to do with trees. The result was a spooky kind of verisimilitude I had never experienced in fiction. The more conventional second half, in which the author brings these characters together, was therefore something of a letdown. They become a motley band of militant environmentalists—much more familiar territory.

In short, the first half of The Overstory seemed to offer a glimpse of some imaginative ground on the other side of the mind-shift. That glimpse was sublime but fleeting. And no wonder. How can we really see, how can we really imagine beyond a shift that the mind has not yet made? It isn’t that we can’t perceive a solution; it’s that we can’t re-conceive the problem while anchored by the ideas that created it. Until we can do that, our solutions won’t have the results intended. So we need shock treatment, it’s tempting to say, we need a conversion experience, we need to fall down on the ground shaking and get back up with our souls clean.

The late systems thinker Donella Meadows could be more sanguine about change at the scale necessary. Cross purposes can be harmonized, she wrote, by “providing an overarching goal that allows all actors to break out of their bounded rationality.” Of course, all have to get behind the new goal. If that task seems overwhelming, Raworth, too, offers a statement that steadies. “We are still in the early days of re-imagining and renaming just what the goal should be.”[6]

For some relevant heart work, cue the Paul Williams song, a standard at weddings, as performed by Curtis Mayfield in January of 1971 at the Bitter End in Greenwich Village.

[1] Rockström, Johan, Mattias Klum, and Peter Miller. Big World, Small Planet. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015, 10.

[2] Raworth, Kate. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think like a 21st Century Economist. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2017, 36.

[3] Raworth, 180.

[4] Raworth, 39.

[5] Rockström, 10.

[6] Meadows, Donella H., and Diana Wright. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2015, 115. Raworth, 51.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

We may be coming at this topic from different points in space that at some point converge. I am not familiar with much of the literature mentioned here (I rarely read fiction, still, I hope to read at least some of the titles you cite!), so I’ll share that which I am acquainted with, if not persuaded by: David Graeber’s recent New York Review of Books article on Robert Skidelsky’s latest book, Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics (Yale University Press, 2018) is, I think, relevant to the idea that we need a “new economic narrative,” although I would make that plural, hence, new economic stories. In any case, not just new narratives, but new models: utopian, pragmatic, and betwixt and between same. Thus I suggest, perhaps owing to audacity, impertinence, or feeble eccentricity, that in addition to Robert Skidelsky’s latest book, we look afresh at Marxian/Marxist political economy, especially that form of which involves a sustained and sophisticated appreciation of the natural world (or ecological and environmental phenomena) as evidenced in recent literature (I recently posted a list of works on ‘Red-Green Democratic Socialism(s)’ on my Academia page), as well as more avowedly or unabashedly unorthodox “economics” perspectives (I happen to believe Marxist political economy, properly understood, is deeply subversive of the regnant economics paradigm, even if more than a few Marxist economists are not adept in making that clear), in other words, works which subsume economic behavior within our larger social and cultural world and worldviews (the latter both religious and non-religious or ethical), such as that well-explored by B.N. Ghosh in Beyond Gandhian Economics: Toward Creative Deconstruction (Sage Publications, 2012) or intimated or even presaged in the writings of Christian Arnsperger.* One more writer/activist I find exemplary on this score is Derrick Jensen (see, for instance, the two volumes of Endgame as well the volume on Dreams; I should note that I have not read everything he’s written).

* Christian Arnsperger is professor of sustainability and economic anthropology at the Institute for Geography and Sustainability (IGD) of the Faculty of Geoscience and Environmental Studies (FGSE). He holds a PhD in economics from the University of Louvain (Belgium) and has been teaching and researching for many years at the interface between economic analysis, human sciences, and existential philosophy.

Patrick, many thanks for your response and your reading suggestions. I wouldn’t be surprised if we find convergence from disparate discourses/disciplines around a) the need to “subvert the regnant economics paradigm,” as you put it, and b) an insistence that the environmental crisis and the economic inequality crisis are inextricable. That’s what I’m seeing, anyway. The doughnut contains that convergence. So does, by the way, the Green New Deal, as Jedidiah Purdy has pointed out in his excellent book/long essay, This Land is Our Land. I do take your point about plural stories and plural, pragmatic models. I don’t find it eccentric at all to “look afresh at Marx.” Marxism is certainly a topic in the Degrowth/Postgrowth conversations that I’m more familiar with. I’m grateful you mentioned your academic page because not only did I find there the Red/Green socialisms bibliography but much, much more of interest. As for Jensen, I am familiar with his The Myth of Human Supremacy, which I believe I’ve written about a bit on the blog. In sum, I take a sliver of hope and also some excitement from the convergence upon fairly specific points of agreement from this wide array, not only of scholarship, but of genre.