On the first day of my Religion in the U.S. course this semester, we did the standard first day of class rigmarole: underlying themes, classroom expectations, and the syllabus; however, I also asked my students to consider how we defined U.S. religion and how the ways that we answer that question might shape our class.

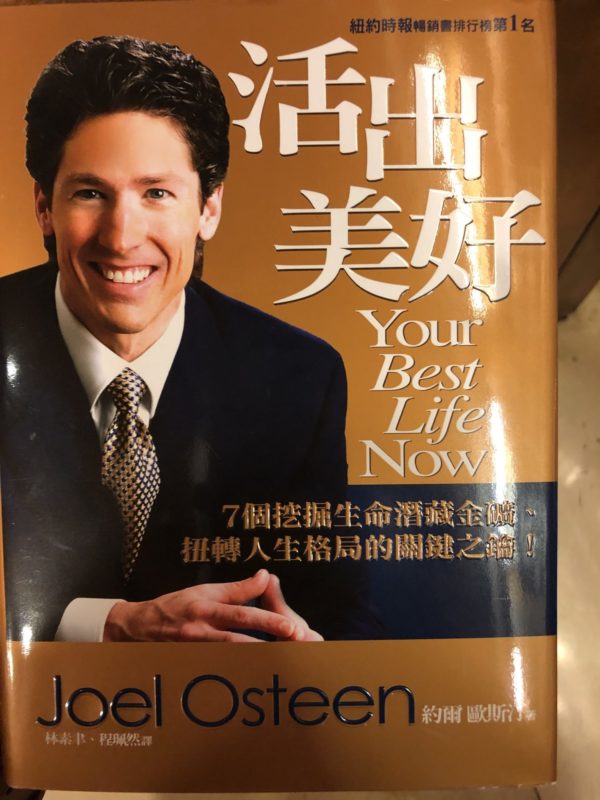

To get the conversation started, I showed my students this picture—a Chinese translation of a book by Houston-based prosperity preacher Joel Osteen. I found the book this summer at a bookstore in Taipei, Taiwan. I asked my students to consider if this was an example of U.S. religion, even though the book was a translation of the English-language original and most likely to end up in the hands of a Taiwanese citizen.

The students formed two lines facing one another and discussed their answers with a partner for a minute before rotating to a new partner. It was something akin to academic speed dating that effectively served to get students talking, introduce themselves to each other and begin to consider some of the fundamental questions that would inform our class.

My students offered an array of answers. Some suggested that it was an example of U.S. religion because the ideas originated in a U.S. context and even when taken abroad, their cultural heritage lingers in ways that make it an example of U.S. religion. Others argued that it was not an example of U.S. religion. They pointed to the act of translation, the geographic location in Asia, and the new cultural context as factors that transformed this religion from an example of U.S. religion to an example of Taiwanese religion.

This exercise got the students thinking from the very first day of class about how U.S. religion and ideas are not necessarily bound by national boundaries. It also firmly situated my course on U.S. Religious History within global context. This broader approach has allowed us to talk more naturally about the international character of places like the Southwest—where I am teaching—the role of immigrants, U.S. imperialism in places like Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico, and missionaries’ outreach globally.

Over the course of the semester, my students and I wrestled with the question of what makes a religion “American” and how solely focusing on geography and borders may obscure the ways that American ideas intersected with broader global currents. As an intellectual historian, I found that this approach provoked a series of important questions that percolated throughout the term. We didn’t all come to a shared conclusion, but the questions themselves allowed us to approach our work in more nuanced and thoughtful ways.

Three questions in particular continued to emerge throughout the semester.

1) How do we define “U.S.” in our approach to U.S. religious ideas?

Inspired by my reading of Daniel Immerwahr’s How to Hide an Empire, I asked my students to think seriously about how we go about defining the geographic scope of our course. Using phrases like, “and then the Mormons fled to Mexico, making a home in the Salt Lake Valley” in a lecture helped to remind students that the borders of the U.S. have changed over time. The logo map, as Immerwahr refers to the map of the U.S. envisioned by many Americans, can obscure the international character of religion in the U.S. and the nation’s moving borders. Students frequently grappled with what we meant when we said, “American” or “U.S.” and how that affected the history we explored together.

2) If any ideas/religious beliefs practiced within the U.S. are immediately considered “U.S.,” do we risk uncritically folding the stories of immigrants or other minority communities into broader narratives that overlook the particularity of their experiences?

Some of my students preferred to define any religion practiced in the U.S. to be a U.S. religion. If we accepted this definition, though, we had to ask what might be lost if we solely relied on geography to determine if religious beliefs and practices should be categorized as U.S. religion.

Could we describe Chinese Buddhist immigrants in the 19th century or Indian Hindus in the 20th century as a U.S. religion even if they did not self-identify that way? Or, should Native American religious traditions, which long predate European contact and the establishment of the United States, be considered U.S. religion when the nation itself represents a colonizing power? If we answer “no” to these questions, how do we thoughtfully integrate the narratives of the colonized and the marginalized into broader U.S. religion surveys?

3) If the U.S. ends at its borders, do we risk obscuring U.S. imperialism and broader global intellectual networks?

This question is clearly related to the previous one, but it’s one that my students tended to agree on more easily. They frequently referred back to annexation and missionary work. The annexation of Texas and Hawai‘i in particular popped up frequently in our discussions about borders and how religious histories long predate the U.S. claiming sovereignty over a region. Teaching in Texas, these histories were particularly poignant. Readings about Christian missionaries also made plain efforts of U.S. believers to spread their understanding of their faith abroad. Students tended to agree that ending U.S. religious history at the borders obscures how freely religious ideas with roots in the United States and the men and women who spread them crossed those same borders.

This final question, however, leads us back to the Joel Osteen book tucked in a corner of a Taipei bookstore. Is this U.S. religion or not? If I picked it up, maybe it would be, but if my Taiwanese friends did, maybe not? If we can recognize that U.S. religious history necessarily extends beyond U.S. borders, when do religious beliefs and ideas transported abroad cease to be identified with the United States?

My students and I didn’t come to many definitive conclusions on these questions, but I’d argue that our learning was enhanced richly by thinking critically about them. By studying U.S. religion in a global context this term, we grappled with a series of questions that helped us to see international intellectual and religious networks and challenged our perceptions exactly of what constitutes the “U.S.” in U.S. religion.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Fantastic post! I’m wondering, how did your students engage with the idea of Osteen in particular?

I chose Osteen because, being in Texas, he’s a particularly public figure, but still, not everyone knew who he was. For our purposes, that was okay actually. With a little background on him, they seemed to wonder how this kind of transaction-based approach to faith (believe enough and you’ll be blessed) bore the marks of broader U.S. culture and if it could ever really be an East Asian faith given the pronounced cultural, religious, and societal differences. The question seemed to be less about whether any religion could be transferred over borders and more could this particular brand of U.S.-based religion ever shed its “Americanness.” He was, for the purposes of the exercise, an ideal example for exactly those reasons. Some had strong reactions to the faith he preached or his overall message, but since we weren’t engaging with those elements as much as asking a broader question about defining U.S. religion, we didn’t get too far into those questions on the first day. All and all, it was a really successful exercise and really helped to set the tone for the rest of the term.