Last week’s USIH conference offered an intellectually exciting program of panels, roundtables, plenaries, and (for the first time) live-recorded podcasts and two keynotes, a program magnificently conceptualized and masterfully chaired by the indefatigable Natalia Mehlman Petrzela. All of us in the organization owe a profound debt of gratitude to Natalia for her creativity and drive.

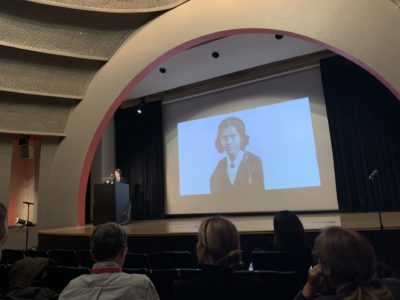

Martha S. Jones delivers the opening keynote for S-USIH 2019

So there were some things we did that were wholly new to us as an organization. But amidst everything new, the fundamental character of our society’s conferences remained unchanged: all this rigorous and creative thinking was a function of community, and this community is dedicated at its core – at least from what I can tell, and from what I can do – to fostering good scholarship, welcoming new participants and new perspectives, and continually exploring the connections between the specialized work we do as scholars and the vital roles we play as publicly-engaged citizens and as mentors and as supportive colleagues who call forth from one another our very best work and our very best selves.

From L to R: Thomas Bender, Caleb McDaniel, Amy Dru Stanley (via Skype!), Leslie Butler, and Christopher Brown meditate on the legacy of David Brion Davis

Let me give you one quick example of how this conference works. On Friday November 8, I was part of a roundtable discussion on “Intellectual History as Moral Inquiry.” We were grappling with the historian’s role as scholar and teacher and citizen, grappling with the ethical expectations we have as historians, and the ethical questions our subjects of study can raise for us. When we were talking about navigating the fraught waters of citizenship and scholarship, my co-panelist Amy Kittelstrom made the simple, honest observation, “My government is caging children at the border, which is completely immoral. But I still pay my taxes. I don’t want to go to jail.” It was a frank and simple summation of the moral dilemma many of us find ourselves in as citizens. I found it especially helpful, because my students’ assigned reading for the week following our conference – just this past week – was Thoreau’s essay on civil disobedience.

Amy’s simple statement – which is true for me as well – allowed me to teach Thoreau in a way that I have not done before. You all know from reading me here that I am generally committed to “pastness” rather than “presentism” in my teaching. But Thoreau’s discussion of the unwillingness of his politically progressive but economically comfortable neighbors to subject themselves to punishment by the state as the consequence of taking a moral stand was newly salient for me, and I taught it differently, and very personally, this time around, borrowing Amy’s observation and applying it to myself. Indeed, those of us who work at public colleges and universities are not just subjects of the state; we are agents of the state. Thoreau’s advice to agents of the state is to quit their jobs rather than be complicit in state-sanctioned injustice. But I will be showing up to work next week nonetheless – just as my students will be showing up to class, just as their parents will be showing up to work, whether they are teachers or TSA agents or attorneys or insurance claims adjustors. All of us in the classroom are rule-followers to one degree or another – that’s a condition of our very presence there, whether we are students or professors.

L to R: Thomas Balcerski, Wendy Wong Schirmer, Eran Zelnik, and Robert Pierce Forbes problematize the “Era of Good Feelings” as both moniker and moment

During the discussion, a student (who was, I believe, from the New School, many of whose students attended conference sessions and participated as part of a class designed to run in conjunction with our conference) brought up the issue of higher law theory as a way of suggesting that I reframe my discussion of John Brown. (Long story short: I had confessed that I throw John Brown under the bus every year to lay the groundwork for a discussion of the Confederacy as a treasonous undertaking and Confederate leaders as traitors who could have been executed for their crimes. An emphasis on the firing on Ft. Sumter and the prosecution of the war by the Confederacy may sound like a minor and rather technical issue of emphasis to you, but it’s a pretty important perspective to convey to students here in the Lost Cause Belt. My class is the first time most of them have been asked to consider the issue.) But by contrasting the fate of John Brown with the fate of, say, P.G.T. Beauregard, never mind Jefferson Davis and Alexander Stephens, I am underscoring the sanctity of the state. The student challenged me to teach about the moral dilemmas of John Brown and others with reference not to law but to higher law theory.

After her plenary interview, Ally Sheedy (R) discusses the historic importance of the film “War Games” with Ben Alpers (L), while Noah Alpers (C) listens in.

At this point in the discussion, David Greenberg gave a plug for a book that examines these debates between legal duties and moral duties, between liberal citizenship and higher law, as they played out in the 1850s: The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul, by Andrew Delbanco. This book looks at how fugitive slaves’ self-liberation and both before and especially after the passage of the 1850 fugitive slave law forced many law-abiding citizens to confront cross over the divide between what the law of the land required of them and what the higher moral law demanded of them. Based on David’s recommendation, I bought the book – which is everything he promised it would be. Not only that, but I’m reading it at the perfect time, since I’m teaching about the Compromise of 1850 next week.

In any case, these interactions on the panel and between the panel and the audience are typical, in my experience, of the USIH conference at its very best, where conference regulars and first-time attendees, established scholars and students, longtime friends and new acquaintances come together to grapple with ideas and their consequences.

Claire Bond Potter gives the Saturday night keynote at S-USIH 2019

This is just one example of how the conference works to bring together people and ideas in fruitful combinations. There are other sessions that I will probably write about in the coming weeks. But honestly, between the stunning opening keynote by Martha S. Jones, the scholarly slugging percentage of the memorial panel reflecting on the work of David Brion Davis, the pitch-perfect mid-conference keynote by Claire Bond Potter, and the is-this-really-happening-here-and-now interview with Ally Sheedy, I am still a little star-struck and (uncharacteristically) at a loss for words.

More later, I think.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

L.D.,

Thanks for the post. Glad the conference was a success.

I don’t quite get the point about the contrasting treatments of John Brown and, say, Jefferson Davis as this contrast relates to “the sanctity of the state.” I would think the decision not to hang or severely punish Jefferson Davis, Alexander Stephens et al. was driven mainly by the policy, expressed by Lincoln and followed in this respect by Andrew Johnson, of emphasizing magnanimity toward the defeated South (and by extension, leniency toward its leaders) in the war’s immediate aftermath (though there were presumably purely pragmatic or logistical considerations involved as well). The decision not to hang Davis didn’t necessarily undermine the federal government’s authority (though it might have been perceived by some as doing so), nor did the decision to hang John Brown necessarily strengthen that authority (though the government did have to prosecute Brown, I think, it didn’t have to hang him to vindicate its authority).

I get the general issue of morality vs. legality and thus I do understand the student’s point about judging Brown by a “higher law” rather than by a legal standard and also the relevance of the Fugitive Slave Law and Northerners’ responses to it, but the rest of the point here is not completely clear to me.

Ok, I just re-read the passage in question and now I understand your reference to the sanctity of the state — it was your way of saying that you have emphasized in class the legal aspects of all these instances. So I guess the moral here is: read a passage twice before commenting on it.

LD: I just recently discovered the protracted debates among theological scholars around John Brown and Kantian ethics. Minor point of the post, but (if you do not already know it) you might be interested in Ted Smith’s “Weird John Brown: Divine Violence and the Limits of Ethics,” as well as reviews of it.

https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=23600