The Book

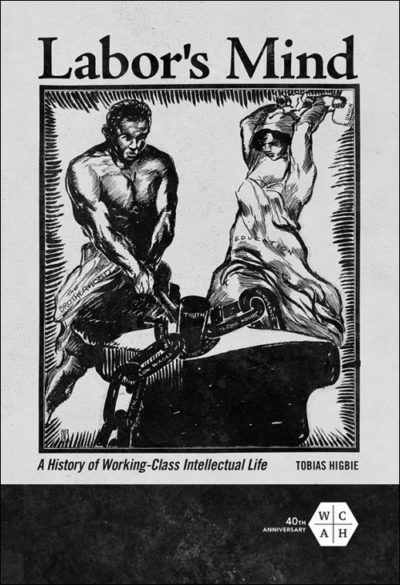

Labor's Mind: A History of Working-Class Intellectual Life

The Author(s)

Tobias Higbie

Tobias Higbie’s Labor’s Mind: A History of Working-Class Intellectual Life

begins with an obvious but rarely-discussed observation: Workers have always been readers, thinkers, and writers. Moreover, the labor movement has thrived through its collaboration with intellectuals and others across the public sphere, in large part because it is this alliance which makes for robust, well-funded, public education. However, the relationship between labor and intellectuals has its own unique history which has served, in the end, to minimize working class intellectual life and ultimately to underfund public education.

Higbie tells the story of how we arrived at this point. In the early twentieth century, workers read the work of intellectuals and intellectuals listened to workers in print and in public forums. University-sponsored “worker education,” while it was sometimes intended as an antidote to radicalism, was central to the organizing work of the labor movement. Labor educators hosted discussions among workers on work, business and economics.

However, starting in the Red Scare of the 1920s, the labor movement shifted organizing tactics to de-emphasize their relationships with intellectuals and instead emphasize workers’ “lived experience” as the greatest hallmark of “true” working class identity. Only “authentic” workers, they claimed, knew what was best for their class. This shift followed the modern conviction that experience is a more authentic mark of understanding than book-learning. The result of this turn, Higbie narrates, is important. In the ensuing decades, unions began to cut ties with labor educators and suggest that rich and educated people had little to offer the working classes. For the sake of organizing the masses, they invented images like the “blockhead” which sought to show workers that they were all, ultimately, interchangeable from the perspective of their employers. Higbie shows that while this turn was somewhat effective in organizing across boundaries of race and religion in the short run of the 1920s and 30s, the strategy cut off relationships with crucial labor allies in academia and journalism. It was detrimental to the labor movement’s long-term goals in expanding a strong welfare state. In the period since World War II, the labor movement has tried considerably to shake themselves of this sense that workers do not need university educators and public intellectuals. They have tried to build better relationships with journalists and academics, but the perennial iconography of brawny self-sufficient workers has made this work difficult.

This is an important book for both intellectual and labor historians. It helps explain how and why labor education has had trouble finding its place in university education over the last fifty years. However, the book’s explanations for labor’s turn against “book learning” are not entirely clear. There are many good reasons why workers turned away from their alliance (or reliance) on intellectuals in this era. First, the Progressive funders of many labor conventions of the early twentieth century also believed that they knew what was best for the working classes. They did not just want to see workers receive better pay, benefits, and time off. Many also wanted to remake working class life—send workers to Protestant churches, reform their marriage and family relationships, change their consumption habits, and minimize their ethnic identities. Muckrakers, ministers, labor mediators and pundits of all types all used strikes to extend their own influence over society. Higbie illustrates the long-term repercussions of labor’s move toward minimizing reliance on Progressives, but the politics of experience also provided a fruitful route for laborers to reject the politics of respectability and retain some semblance of their cultural identities.

Second, the blockhead is a vivid caricature of a dull worker, but the book left me wishing I could learn more about why this iconography became so pervasive and powerful. Of course, as Higbie suggests, the pervasiveness of blockhead iconography did not actually equate with less vibrant, working class intellectual life. The blockhead was an icon invented by the Industrial Workers of the World for the purposes of organizing. However, it would have been helpful to explore what types of books and magazines workers were reading in the early twentieth century, and why the labor movement officially rejected certain forms of book learning in favor of others.

Early twentieth century intellectuals, especially religious leaders, taught college classes and led forums with union members all over industrial cities such as New York, Chicago and Detroit in the early decades of the twentieth century. As Matthew Pehl illustrates vividly in his Making of Working Class Religion, workers were deeply engaged with a life of ideas. Communists, socialists, and other labor radicals, however, were often suspicious that the materials which religious leaders distributed were not really best for workers or the future of class solidarity. Moreover, while the labor movement did cut off some of these relationships with Progressives in the early twentieth century, in other cases these relationships fell apart because their so-called allies rejected them. The Red Scare raised many hard questions for labor leaders as to who were their “real” allies and who were their fair-weather friends. Religious leaders and communists deeply disagreed, but alliances with each of these groups came with strings attached. As Leilah Danielson has shown in her work on Brookwood Labor College, the Communist Party imposed sharp restrictions on what should and should not be debated among workers. Working class intellectual life was not just strengthened by alliances with intellectuals. It was also constrained.

Therefore, when labor leaders warned “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing” (71), was it because of the communist/radical fear of religious and reform-minded Progressives? Was it about a rejection of communist influence in favor of another more “authentic” and organic ideal? Was it really so detrimental that the labor movement sought out some semblance of intellectual independence among these competing groups?

Finally, I wonder if the story would have shifted had the book engaged with the literature on religious testimonials and authenticity in the twentieth century. In Ronald Rogers’ The Struggle for the Soul of Journalism: The Pulpit versus the Press, 1833-1923, we learn of the ways that “authenticity” was a source of tremendous cultural capital in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Rogers argues that journalism, as a profession, arose from the cache of “authentic” and “experiential truth” in the early twentieth century. As Timothy Gloege shows in his Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism, evangelical fundamentalism was sold to the masses during the same era as a “pure” product that came right from Scriptures and without a meddling intellectual. As Gloege explains, Dwight Moody marketed a “pure” fundamentalist theology akin to “pure” Quaker Oats.

Perhaps we need to center dialogues of authenticity in our histories of the twentieth century labor movement. Progressive reformers, labor educators, communists, religious leaders, and journalists all deployed rhetorics of authenticity to remedy the ills of industrial capitalism in the early twentieth century. Higbie shows the negative, long-term repercussions of the labor movement formally rejecting their alliances with professional intellectuals. In short, the labor movement lost its foundations for demanding a significant public investment in public education.

The book is persuasive in its argument that this move lost the labor movement some if its greatest allies in their struggle for a crucial component of a strong welfare state. However, was there anything gained in this turn away from Progressive allies? In that alternate universe where the labor movement retained its relationship with public intellectuals, would the labor movement have also lost some of its independence? Would it have been driven out of existence by the Red Scare? Are there other avenues the labor movement might have pursued to support public education that would have engaged intellectual allies without relying on their dominance?

We need more histories that lead us in unpacking the roots of a underfunded public education in the twenty-first century. Labor’s Mind should serve as a starting point for further discussion among students of labor, cultural, and intellectual history.

About the Reviewer

Janine Giordano Drake is Assistant Clinical Professor of History in the Indiana University History Department, where she specializes in US labor, social and religious history. She has authored a number of articles and chapters on race, class, and gender in the Social Gospel movement and the Religious Left. She co-edited Between the Pew and the Picket Line (University of Illinois Press, 2015) and is (still) completing her manuscript “War for the Soul of the Christian Nation: The Socialist Movement and the Protestant Churches, 1880-1920.” At Indiana University, in addition to teaching undergraduate and graduate courses, Janine works with the Advance College Project as a public historian. In this capacity, she helps prepare Indiana high school students for college by training and resourcing Social Studies teachers to lead college-level history courses.

0