The Book

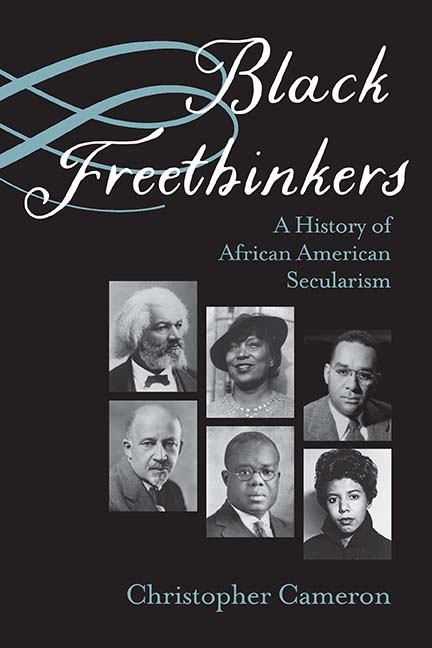

Black Freethinkers: A History of African American Secularism. (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2019)

The Author(s)

Christopher Cameron

Christopher Cameron’s newest book, Black Freethinkers: A History of African American Secularism, is an attempt to rectify what he sees as a glaring assumption in African American history. “The assumption that atheism and other forms of nonbelief are the preserve of whites,” wrote Cameron, “has caused most historians and scholars of religion to ignore or downplay their existence among African Americans” (ix). Indeed, in Black Freethinkers, Cameron goes to great lengths to showcase the long history of freethinking, agnosticism, and atheism among prominent African Americans. In the process, Black Freethinkers also demonstrates the importance of not just gathering sources but thinking about how to analyze such sources.

One of the strengths of Black Freethinkers is the fact that it is, in one sense, a survey of African American history from the perspective of non-religious thinkers. Indeed, the narrative of the book—from the earliest days of slavery in British North America all the way until the twenty-first century—should offer historians and other readers a different way to think about the African American past. Cameron’s use of slave narratives is a strong example. The focus in Black Freethinkers in Cameron’s analysis of the narratives is on how the formerly enslaved look back on their experiences with religion, especially Christianity. Certainly, their critiques of religion were also, from Cameron’s point of view, also instrumental in showing how “black freethinkers advanced the cause of abolition while also contributing to the growing freethought movement in the mid-nineteenth century” (4).

The ways in which African American freethinkers combined their irreligious views with other, better-known struggles for freedom and justice among African Americans is another key argument of this book. For Cameron, African American freethinkers such as Frederick Douglass, Zora Neal Hurston, W.E.B. Du Bois, and James Forman were all important precisely because their skepticism about religion wasn’t incidental to their better-known stances on civil rights but were central to them. For example, figures such as Douglass and Richard Wright delivered stinging critiques of the African American church, seeing them as obstacles to the broader Black Freedom Struggle in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Likewise, the role of gender is a critical part of Cameron’s analysis, as many of the prominent African American female freethinkers saw a tie between a critique of the church and their own push for feminism. Nella Larsen’s book Quicksand offers a story that centers around Helga Crane, a woman who is dismayed by the importance of religion in numerous African American institutions—and the seeming hypocrisy of those who hold powerful positions in the African American church. The freethinking of individuals such as Lorraine Hansberry and Alice Walker is not incidental to their critiques of capitalism, racism, and misogyny, but are at the center of them.

The variety of famous voices in the book, all espousing freethinking, agnosticism, and atheism, may be surprising to people who only know African American historical figures for their stances against racism. But Black Freethinkers does focus only on such important figures. This is not a critique that should dissuade anyone from reading the book—in fact, the book opens up questions about the links not only between freethinking and African American history, but some of the sources in European and American philosophy and intellectual debate that are also read and absorbed by African Americans. But there is another book waiting to be written about how African American freethought looks on a local level. This would be a work of intellectual history that would, once again, raise questions about whose thoughts we privilege in the field. The good news is that, whoever decides to take up that mantel, has a good starting place with Christopher Cameron’s Black Freethinkers.

About the Reviewer

Robert Greene II is an Assistant Professor of History at Claflin University. He received his PhD from the University of South Carolina in 2019. Dr. Greene’s specialty is African American History in the 20th century and the American South after 1945. He has been published in The Nation, Jacobin, Dissent, Scalawag, among other publications, along with the blogs Black Perspectives and Teaching United States History. Dr. Greene is also the Book Reviews editor for S-USIH.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I was quite happy to learn of this book for a number of reasons (some of which I share in what follows), despite the fact that I often find myself defending religious or spiritual perspectives and worldviews on the Left. At the same time, I’ve tried to elaborate how non-religious worldviews and philosophies can count among their adherents those who are “spiritual,”* albeit of course with a more generous definition of spirituality than one dependent on religion(s) for its essential meaning. On the other side of the world, if you will, there happens to be a renewed or at least more sustained academic and philosophical interest in Indic (or Indian) materialism (C?rv?ka/Lok?yata), both among Indians in India as well as among scholars studying Indian philosophies generally, the latter having heretofore virtually ignored when not simply dismissing (rather unfairly, as when they’ve been depicted as crass hedonists) these non-religious philosophical views. This, I trust, can only be a heartening development if only because it enables us to see and appreciate how those who are non-religious can be morally motivated, acting in an ethically ennobling way as much as (and sometimes more than) anyone who happens at the same time to be religious. And of course it is a reminder, should we need one, that morality is not dependent (as the Dalai Lama frequently notes) on religion, an anthropological, historical, and logical fact that many people in the U.S. fail to acknowledge, indeed, too many folks in this country simply think that to be non-religious is to be immoral, even in a time and place when those who are avowedly if not ostentatiously religious often behave immorally (conspicuously so) or in a morally dubious manner. And of course while religion is neither a sufficient nor necessary condition of morality or an ethical life, that does not mean that religious worldviews might on occasion have something to offer morality and ethics, particularly in the life of any one individual. Unfortunately, the public and private polemics generated by the so-called “new Atheists” and their acolytes has only simplified matters that are rather far more complex (and thus rather more interesting and ‘true to life;), thus a book such as Cameron’s is both a welcome and worthy contribution to that reality.

See, for example, this: https://www.religiousleftlaw.com/2013/05/the-marxist-spirituality-of-clr-james.html

and this: https://www.religiousleftlaw.com/2017/10/toward-a-secular-spiritual-ethics-for-all-of-us.html