2019 is a year dense with anniversaries. 1969 and 1619 are the two which have probably received the greatest notice from American historians, but a special feature in the Journal of American Studies (JAS)—which is based in British and edited by Sinéad Moynihan and Nick Witham—five scholars demonstrate the importance of 1919, 1939, 1949, and 1989 as well.

This roundtable came out of a one-day conference on “Marx and Marxism in the United States,” which was held earlier this year at the University of Nottingham. That context informs the various contributions, each of which explores a different pivotal moment for the left in the United States. Christopher Phelps organized the roundtable and also wrote the contribution for 1919[1]; Jennifer Luff wrote on 1939, Alex Goodall on 1949, Jonathan Bell on 1969, and Molly Geidel on 1989.

In his introduction to the roundtable, Phelps considers the way Marx used specific years (1648, 1789, 1848) as “synechdoches” or “shorthands” to capture the key instants when the lines of class conflict flashed into clarity. Or as Phelps puts it, “A single year… may stand out in history as a date when the resolution of social contradictions, the coming to fruition of material forces, or the culmination of class battles became manifest.” Such a method might imagine classes as tectonic plates, grinding unnoticed toward and away from one another gradually, incrementally, visible only by their spectacular, punctual, and yet unpredictable cataclysms. Marx’s great narrative gift—nowhere better displayed than in The Eighteenth Brumaire—was his ability to toggle between those two historical moods, the slow and the sudden, never wholly entering one without pulling along intimations of the other.

That’s a tall order for any historian to replicate, and those assembled in this roundtable are hemmed in a bit by the artificial frame of the anniversary—a setting which generally leaches any feeling of spontaneity or surprise from history. Despite that, the participants of the roundtable make good on their intentions to demonstrate both the eventful importance of these specific years and the larger social processes which they seem to have crystallized.

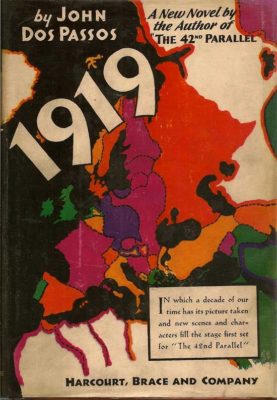

Phelps sets up his examination of 1919 by asking why the novelist John Dos Passos decided to title the middle volume of his great trilogy U.S.A. “Nineteen-Nineteen.” 1917, he notes, was a more obvious choice for its overwhelming historical importance—the Armistice, the Russian Revolution. However, “1919 was, for [Dos Passos], the moment when American capitalism’s transformation from proprietary to corporate capitalism was over – as well as the year when it became crystal clear that the war had left not only multitudes dead in Europe’s trenches but also two domestic casualties: American liberalism and American radicalism.” To adapt a line from Henry May, 1919 was the last of the “first years of our own time.” But it was also an enormously consequential year on its own, thanks to the “confluence of three occurrences: strike wave, race riots, and Red Scare.” Phelps sums up the meaning of this confluence in a single potent paragraph:

Phelps sets up his examination of 1919 by asking why the novelist John Dos Passos decided to title the middle volume of his great trilogy U.S.A. “Nineteen-Nineteen.” 1917, he notes, was a more obvious choice for its overwhelming historical importance—the Armistice, the Russian Revolution. However, “1919 was, for [Dos Passos], the moment when American capitalism’s transformation from proprietary to corporate capitalism was over – as well as the year when it became crystal clear that the war had left not only multitudes dead in Europe’s trenches but also two domestic casualties: American liberalism and American radicalism.” To adapt a line from Henry May, 1919 was the last of the “first years of our own time.” But it was also an enormously consequential year on its own, thanks to the “confluence of three occurrences: strike wave, race riots, and Red Scare.” Phelps sums up the meaning of this confluence in a single potent paragraph:

What 1919 demonstrates, then, is double-edged with regard to Marxism. It shows that America has had class struggles comparable to – indeed, related to – those of Europe, despite the American ideology’s denial of them. The strike wave of 1919 was nothing if not at heart a clash over how to divide the surplus: profits or wages? At the same time, 1919 illustrates how American history has thrown up tremendous obstacles to class consciousness and class solidarity, let alone revolution. The year’s race riots and political hysteria epitomize how American working-class cohesion has so often been short-circuited.

Jennifer Luff positions 1939 as a kind of tipping point for the fate of a variety of homegrown American Marxism, but also critiques previous chroniclers of the Popular Front—including Michael Denning—for writing its history without sufficient attention to the transnational dimensions of left politics. Taking her cue from Earl Browder’s famous line that Communism was twentieth-century Americanism, Luff shows how the pressures of the late 1930s—especially the show trials, the Trotsky Commission, and the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop—caused the hopes of an autonomous American path for Communism to founder. Especially after the odd pause that was the U.S.-Soviet alliance during the War, “There was no space for American Communism outside Stalin and the discourse of totalitarianism.”

That search for an alternative to Soviet control of international Communism is the theme of Alex Goodall’s piece on 1949. Emphasizing that the “loss” of China was at least as if not more significant in triggering the full-blown American panic attack as the Soviets testing their first atomic weapon, Goodall argues that ironically it was American leftists—especially Communists—who failed to understand the global implications of Mao’s victory, at least at first. Eventually, however, “For radical Americans, and African American radicals in particular, Mao’s example and theses would offer a new path for radical protest, one that was less deferential to the white working classes, less concerned with rigid interpretations of historical materialism, and less interested in Europe.”

Jonathan Bell uses 1969 as a lever to open up the broader dimensions of a rapidly changing relationship between gay liberation and Marxism, and particularly between gay activism around health care access and anticapitalist theory. “My research into the public policy dimension of the rights revolutions,” he writes, “demonstrates clearly the close relationship between access to money and LGBT identity. Having to pay for health services in the United States did not simply reveal the class dimension to LGBT rights, but also placed the transactional element of capitalist exchange at the heart of the development of LGBT identity.” Bell convincingly argues that, in the two decades after 1969, gay liberation challenged American Marxism to expand its critique of global capitalism, adding new layers of sophistication and eroding longstanding prejudices within the left against LGBT people.

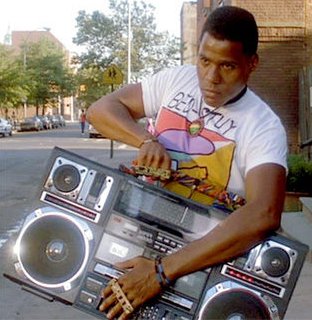

Finally, Molly Geidel looks at two iconic symbols of 1989 to illustrate the limits of leftist imagination at the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Geidel argues that 1989 found the left in the UK and the USA imaginatively depleted: focused on protecting the gains of previous decades, social and economic transformation was no longer part of the left’s horizon. This meant that the original cultural markers that were produced at this time were generally weak and ambiguous—easily co-opted by critics of the left. One such symbol was the boom box, and Geidel reads both Say Anything and Do the Right Thing as inspired but fragile attempts to imagine a feminist and antiracist popular culture respectively. Geidel also notes the ambiguity of Tank Man, the anonymous Chinese man who defied a column of tanks in Tiananmen Square that year. For Geidel, Tank Man is an example of how much more prepared the right was to plug new symbols into their revived worldview of “destruction and renewal”—a worldview which was borne out in the rapid invasion of Panama, an operation which stunned a lethargic left. For Geidel, 1989 stands as a case study in how crucial it is for the left to have a vivid and inspiring cultural politics—without it, she suggests, the left implicitly submits to the right’s worldview and operates within its confines.

Finally, Molly Geidel looks at two iconic symbols of 1989 to illustrate the limits of leftist imagination at the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Geidel argues that 1989 found the left in the UK and the USA imaginatively depleted: focused on protecting the gains of previous decades, social and economic transformation was no longer part of the left’s horizon. This meant that the original cultural markers that were produced at this time were generally weak and ambiguous—easily co-opted by critics of the left. One such symbol was the boom box, and Geidel reads both Say Anything and Do the Right Thing as inspired but fragile attempts to imagine a feminist and antiracist popular culture respectively. Geidel also notes the ambiguity of Tank Man, the anonymous Chinese man who defied a column of tanks in Tiananmen Square that year. For Geidel, Tank Man is an example of how much more prepared the right was to plug new symbols into their revived worldview of “destruction and renewal”—a worldview which was borne out in the rapid invasion of Panama, an operation which stunned a lethargic left. For Geidel, 1989 stands as a case study in how crucial it is for the left to have a vivid and inspiring cultural politics—without it, she suggests, the left implicitly submits to the right’s worldview and operates within its confines.

The roundtable as a whole is a rapidfire but coherent piece of historical analysis. Although Phelps in his introduction emphasizes the differences among the contributors, what struck me was, in fact, their common grounding in a tradition of cultural materialism going back to Raymond Williams and running through Stuart Hall and Michael Denning. This was a heartening example of what cultural materialism—a mode of analysis that is in abeyance somewhat at a time when political economy has become a more common theoretical language for young leftists—is able to do; it proves that there is much vitality in a culturalist approach to Marxist history.

Notes

[1] Robin Vandome co-organized the conference.

0