Editor's Note

This is the final post in a series that uses the study of nineteenth-century Dutch immigrant settlements in Iowa, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin to pose larger questions about how the international consciousness of rural communities in the nineteenth century challenge not only our understandings of the rural Midwest, but also of conceptions of American and European imperialism, settler colonialism, and worldwide missionary efforts.

Last week I moseyed down to a mixer at my apartment complex, enticed to take a break by the promise of libations and snacks. While there, I struck up a conversation with a couple, and we exchanged standard pleasantries. One of the guys was a botanist and the other a civil engineer. I introduced myself as a historian. They asked what, specifically, I studied, and I shared with them that I work on rural internationalism and religion in the nineteenth century.

“You mean to tell me that people in rural America were actually paying attention?” one of them asked with a tone of disbelief.

“Yep. They talked about places like China, India, and Japan all the time,” I responded.

Not wanting to scare off potential new friends, I restrained from exploring in detail the international consciousness of these rural folks; however, the reaction from these new acquaintances reminded me of some prevalent perceptions of the rural United States and the rural Midwest in particular.

As I wrap up this series on the international consciousness of a small rural Midwestern community, this brief conversation was a helpful reminder of the prominent misperceptions of the histories of many remote communities.

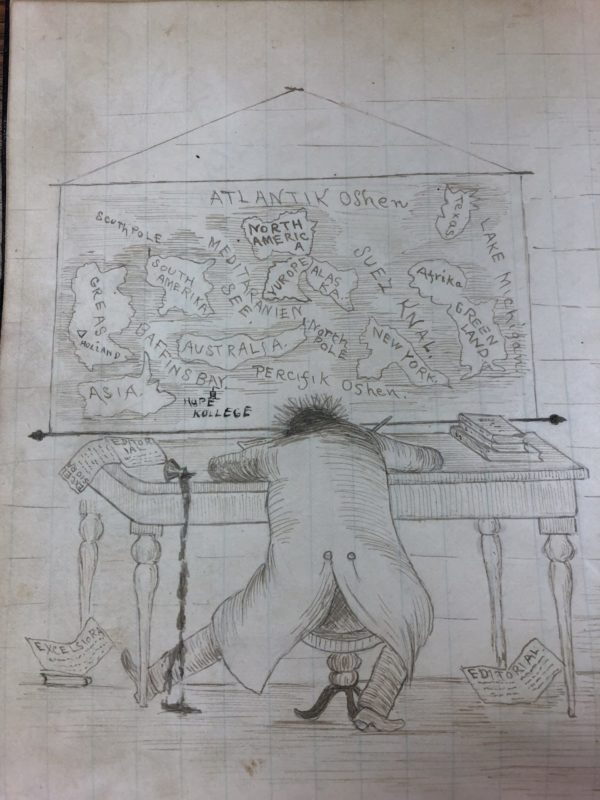

This series featured stories of how men and women from the rural Midwest understood their place in global contexts, highlighting discussions of China, Japan, Hawai‘i, the Arctic and Africa; however, these few examples simply offer a representative sample of the many places these rural folks regularly discussed. They wrote articles about India, Mexico, Korea, Indonesia, Turkey, Russia, and many other nations. In newspapers, letters, and personal writings, international affairs consistently appeared. These folks had blind spots, of course. They almost never mention South America and completely overlook Australia. Nevertheless, there is a rich internationalism expressed frequently in the writings of this community in the late nineteenth century.

Aside from recognizing the presence of this robust international vision, there are a few themes that run throughout this series’ posts and the larger corpus of writings that informed them.

Ideas of civilization and progress shaped this rural vision.

Throughout these writings, rural immigrants focused intensely on the ideas of progress and civilization. These words pepper the articles written by these men and women, yet they never take the time to define them explicitly; however, they clearly associate progress and civilization with processes of Westernization and Christianization.

Moto Ohgimi, a Japanese student in Holland, Michigan, during the 1870s, perhaps articulated the dominant views of this community most concretely when discussing his homeland.

“It was truly wonderful that Japan, which was fifteen years ago considered as of the savage country of the Pacific Islands, is now becoming the most progressing land in Asia, adopting the ways of western civilization, casting down their bigotries of the old religion… The progress of civilization is most remarkable in the capital, Yedo, where there is now a Christian church in which the true word of God is preached, every Sabbath, and even by native preachers whose congregations are constantly increasing.”[1]

Ohgimi cast a vision of Japan as an ascendant and progressing civilization. Westernization and conversion to Christianity played critical roles in such a characterization. A convert to Christianity and educated in the Midwest, Ohgimi clearly equated progress with the adoption of western manners and mores and civilization with a turn toward Christianity.

Religion played a major factor in determining how these rural folks viewed other nations and the people who lived in them. Their belief that Christianity sat at the apex of human development meant that they often judged other people based on their friendliness toward evangelism. For instance, they heralded Hawai‘i because they perceived the islands to be a success story for Christian missions. Africa, on the other hand, received their ire, in part, because they presumed the continent to be resistant to Christian missionary efforts.

Ultimately, a commitment to their conceptions of progress and civilization tie together this community’s engagement with Africa, China, the Arctic, and a host of other places throughout the globe. Their religion drove them to try to proselytize the world, and these ideas told them what successful endeavors should look like.

In some ways, the racism, imperialism, and colonialism of this rural Dutch community is unremarkable for the final decades of the nineteenth century; however, most rural immigrant communities living in remote enclaves are less frequently connect them to these pervasive ideologies. Furthermore, narratives about potentially naïve rural communities content to mind their own business break down under closer scrutiny. These men and women certainly wanted to build their own towns and undeniably worked to limit any external interference with their own affairs, but that didn’t mean that they did not want to engage the wider world or influence efforts to extend their religious and imperial influence.

These men and women were provincial internationalists. While rural communities focused much of their energy on furthering their vision for their own little towns spread throughout the Midwest, they did not let their local vision dampen their interest in meddling in global affairs. In fact, their zealous, society-building vision propelled them further onto the international stage, encouraging them to develop a robust but flawed understanding of the world, all in an attempt to spread their ideas of progress and civilization.

[1]Moto Ohgimi, “Foreign Correspondence: Yedo,” Excelsiora 4, No. 11 (April 1874), Excelsiora Collection, JAH.

0