Next week I report to work at the last job for which I will ever apply, in academe or out of it. I have been hired as a full-time professor of history at Collin College. I will be teaching a five/five load – between 150 and 175 students per semester – including a couple of sections of dual credit history at a local high school in Allen, Texas.

I am beyond thrilled. See, teaching at a community college – specifically, at this community college, which is a twenty-minute drive from my home – is why I went to grad school in the first place. This is my dream job.

My last round of interviews at Collin was in mid-April, but the job offer didn’t come until late May. I was on vacation with my sister when I got a phone call from the dean with a verbal offer, which I accepted immediately. I got the written offer a couple of days later, and my hire was approved in late June.

My last round of interviews at Collin was in mid-April, but the job offer didn’t come until late May. I was on vacation with my sister when I got a phone call from the dean with a verbal offer, which I accepted immediately. I got the written offer a couple of days later, and my hire was approved in late June.

But I held off on saying anything specific about it here because I was afraid that it somehow wasn’t real, that at the last moment someone would say, “Never mind, it seems there has been a clerical error; we don’t need you after all.” The precarity of the academic labor market exacts a steep psychic toll. When at last my contract came this week, an enormous weight of worry finally slipped from my shoulders. It’s real. I am — officially, finally — employed.

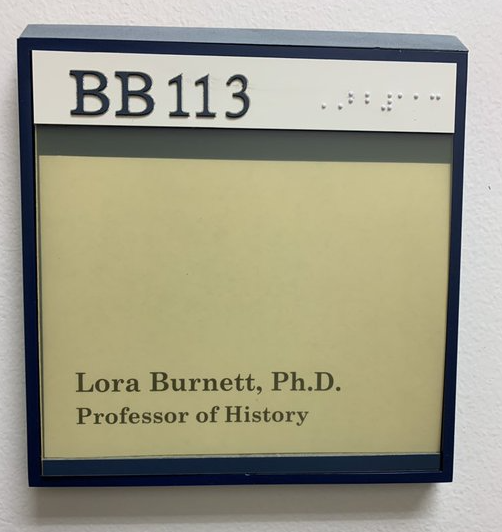

I have my own office, with a desk and chair, a phone, a computer and printer, a filing cabinet, a bookshelf, and a chair for the students who come to office hours. They even put my name on a sign by my office door, a door that locks, so I can keep my stuff there between my classes and know it will be there when I get back. These are not favors or gifts or luxuries; they are the basic equipment that I need in order to do the job for which I have been hired, a job that requires me to be on campus Monday through Friday and hold six office hours per week. Gotta have your own office for that!

These basic arrangements feel like luxuries only because I am coming out of years of contingent employment when I might share an office with one or two or four or eight other people (I think my personal record was eleven office mates sharing two desks), when I might or might not have access to a campus phone in case of an emergency, and when my assigned office space might change from semester to semester. Those are the conditions under which many adjuncts labor, even at major research universities – if, that is, they are fortunate enough to be given office space at all.

So I am most grateful that the place where I am going to work equips its profs with what we need in order to teach undergraduates – which is, after all, our primary responsibility.

I feel that responsibility especially keenly this fall. Collin College and Allen, Texas have both been in the news recently. I don’t know what classes the El Paso domestic terrorist took while enrolled as a student at Collin, but I can guarantee you that he was not taught about some mythical “Hispanic invasion” of Texas in any history classes he may have taken there. That’s a flawed, pernicious idea he picked up from somewhere else, and it’s not the fault of his professors that nothing was able to dislodge it.

But it’s a reminder of what all college history professors encounter when we step into a classroom. Our students are not blank slates; they come into class with their own ideas of what “real history” is. Some of those ideas are perhaps erroneous but relatively harmless; some of those ideas are pernicious and, as springboards to action, manifestly dangerous. For the most part, though, our students are not nearly as interested in the past as we are; they just want to pass the class and get the requirement out of the way. For the vast majority of our students, the U.S. History survey will be the last history class they ever take, and they are only taking it because they have to.

That’s a tough crowd. But it’s a good crowd, too – any room full of young and not-so-young people who are seeking an education to better their chances in life is a room full of hope, a room full of potential, a room full of promise.

I am beyond grateful for the chance to step into such a room five days a week, grateful for the chance to convey to my students, to the best of my ability, that in the hard work of gaining a clear understanding of the past, in the hard work of striving to get the history right — to move beyond the dull, deadening myths of mechanistic inevitability and uncover the dynamism of contingency and consequentiality in the clash of all-too-human wills — in doing this hard work there is hope and potential and promise. For “[w]hen…history brings to the fore a hitherto unknown past, it causes people to see how the horizon of the present is not the horizon of all that is.”*

The past was a made thing; the future will be a made thing too, and we are its makers. Here is great hope, and potential, and promise — only let us take care how we build.

So I teach, and so I believe.

____________

*Allan Megill, Historical Knowledge, Historical Error: A Contemporary Guide to Practice (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 40.

0