Many states, including Texas, still require two semesters of U.S. history as part of an undergraduate education. (Texas also requires a full semester of either Texas history or Texas government.) Higher education accrediting agencies (for Texas, that would be the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools) set minimum standards / expectations for what these required courses will entail. Various public higher education systems maintain their own curricular standards at the institutional and departmental level, standards designed to address all these requirements as well as any other concerns or priorities of the faculty or the university in question.

These institutional standards are often reflected in mandatory boilerplate language professors must include on the syllabus. One iteration of that language is the affirmation that the course will give an overview of the political, economic, social, cultural, and (sometimes) intellectual history of the United States.

These institutional standards are often reflected in mandatory boilerplate language professors must include on the syllabus. One iteration of that language is the affirmation that the course will give an overview of the political, economic, social, cultural, and (sometimes) intellectual history of the United States.

I find it useful to linger over that language at the start of the semester and explain what sets those different approaches to history apart from one another as well as what connects them. Below is a brief writeup that I post as a standalone document on the course homepage. I have called it “History Framework,” but it probably needs a more descriptive title.

This is how I distinguish these various overlapping branches of historical inquiry in teaching, and I explain them in this order – often the exact reverse of how they are listed in various mandatory guidelines. The last shall be first…

If you find this framework useful, please feel free to adopt or adapt it for your own courses, with a hat tip to yours truly. And if you have any suggestions for how to revise this framework, please feel free to add them in comments below.

HISTORY FRAMEWORK

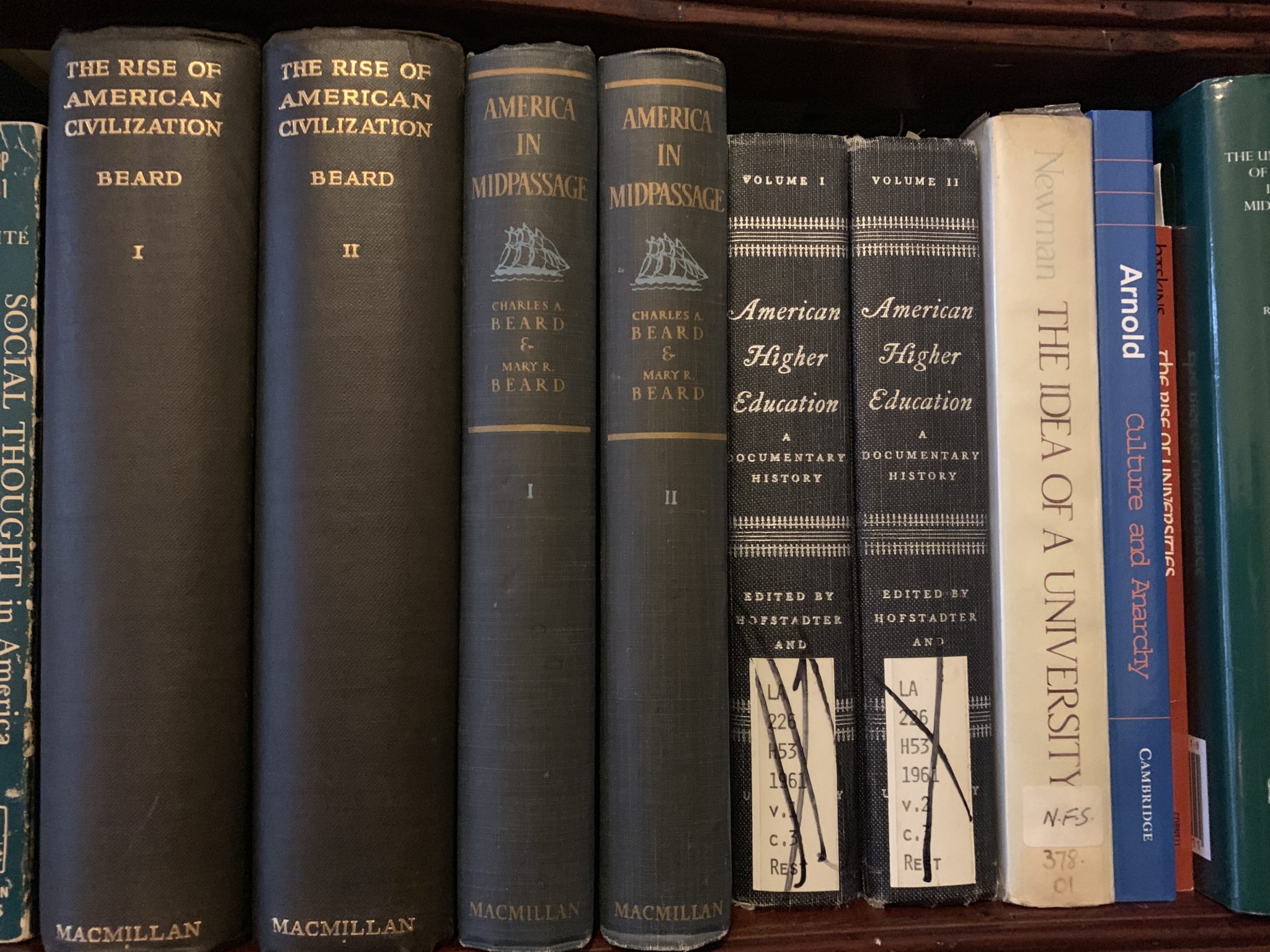

Intellectual History– often deals with explicit statements of what people thought, believed, studied, valued. Such explicit expressions can be found in essays, philosophical treatises, religious creeds, works of theology, sermons, letters, scientific reports, college course catalogs, legal codes, and so forth. However, in this class we will learn that there are many more kinds of sources we can use to discover the ideas and beliefs of people from the past than works of “high” philosophy or speculation. People from all walks of life have ideas about themselves and their world and have found all kinds of ways of expressing those ideas, either purposefully or incidentally. We can look carefully at a wide range of sources to catch a glimpse of the meaning people made of their own lives in the past. So we will work on developing an expanded understanding of what “counts” as a source for intellectual history.

Cultural History

– deals with implicit / informal evidence of what people in all strata of society thought, believed, valued, enjoyed, and admired; what they feared and/or disapproved of; what folkways or traditions they preserved; thus, more generally, how peoples’ beliefs, ideas, and values found expression in indirect ways or in informal settings. Tavern songs, popular poetry, art, drama, fiction, decorating trends, church hymns, fashions of dress, conduct manuals, team sports and their rules of play, architectural forms – all these types of sources can tell us something about what people valued and believed, though these types of sources do not generally feature people spelling out their beliefs in the form of explicit verbal statements/propositions. Nevertheless, there is significant overlap between cultural history and intellectual history, because ideas are everywhere, evident in all kinds of sources, and people are always expressing ideas and values by the actions they take and the things they spend time on.

Social History– seeks to recover what people’s daily lives were like, particularly for groups of people who were not part of the most highly educated and affluent elite, and who therefore had less opportunity to leave written testimony in their own words regarding their own ideas, beliefs, and experiences. Day-laborers, craftsmen, indentured servants, slaves, Native Americans, women, immigrants, colonizers, colonized people, farmworkers, prisoners, convicts, factory workers – such people have shaped history profoundly, but their individual experiences are largely inaccessible to us because they often did not have the leisure or resources to tell their own stories. We can try to recover and understand the experience of such groups of people through statistical analysis of data we have from other sources (wages, prices, cost of living, average time of travel, life expectancy). We can also look for places where less privileged people do enter into the historical record: in court cases, in coroners’ reports, in news items, in advertisements for runaways.

Economic History– focuses particularly on the material conditions, market relationships, available or desired resources, and manifold technologies (broadly construed) that shaped people’s working lives and overall well-being (commodity crops, transportation infrastructure, manufacturing processes, manufactured goods, prices, jobs, trade routes, assets and liabilities). Economic history overlaps to some degree with social history, because economic history helps us understand how and why some groups were able to amass more resources than others, and social history uncovers the human actions and intentions behind how the economy functions and changes. Historians generally do not study the development of the economy as something “natural” or “automatic” or governed by “laws,” but as a result of decisions based on people’s beliefs and values.

Political history– focuses on the systems and past/potential standard-bearers of authority and law in society. Elections, wars, treaty negotiations, debates in a Congress or a parliament, rebellions against monarchs, battles over royal succession, court decisions, imperial edicts, voyages of conquest, legal codes, customary penalties for crimes – all these are matters that can be treated as political history. Conceived narrowly, political history could be summarized as “dudes and dates” – but as the other approaches to the study of the past described above demonstrate, there’s so much more to understanding how a society has developed than learning the names and party affiliations / loyalties of the people who have been regarded as its leaders.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I think the description of political history could be fuller. I would add something like: “also studies how groups of like-minded persons organize themselves to further their interests and ideologies through political parties, coalitions, and/or grassroots movements, as well as how the range of politically relevant ‘actors’ has changed over time.”

Thanks Louis — I could probably add a few sentences beginning, “Conceived more broadly, political history can include…”

It occurred to me while reading the Durant volume on Greece that U.S. Presidential Elections end up functioning much like Olympiads (at least in how I teach the survey): they’re a useful common means of dating various developments in US history, or in anchoring them to a common event, but they’re not always particularly compelling on their own as “events” (not for me, anyhow). I tend to focus on more longue durée developments. It’s pretty rare for me to discuss the specifics of a Presidential election — with, of course, a few exceptions (George Washington, Adams v. Jefferson, The Corrupt Bargain, 1828, 1860, 1876, 1896, 1912, 1928, 1932, 1960, 1972, 1976, 1980, 2000, 2008). I mean, I give a passing nod to elections as we go along, but those are the only ones where I am tempted to linger. There is a reason that I list political history last in my overview of the kinds of history we are surveying!

I have noticed that political history is usually listed first in the catalog descriptions of the survey at the institutions where I have taught. As for intellectual history, it was not listed at all in, for example, the Tarleton State catalog descriptions of the survey, but you can bet it was listed first on my syllabus, because I’m always teaching the survey as a survey of American thought and culture (with a dash of economics, social history, and politics).

And teaching it that way makes sense, esp. given your interests and areas of expertise. Some elections are compelling as events, others not so much, and if there are students interested in particular elections they can be encouraged to research them on their own.

Love the article and breakdown.

One small correction: Texas Requires 6 hours of US History (3 can be Texas History specifically), usually done in survey courses but not required AND it requires 6 additional hours of political science/government (3 in US govt. and 3 in Texas govt).

Yes, I know. I didn’t want to get in the weeds of which classes swap out for which. But in my experience most students take the Texas history course to cover the state government requirement, though that no doubt varies by institution, faculty, ourse offerings, and advising. It is a common substitution, which is a boon, I guess, for history departments. The fact that Texas requires that at all seems very Texas. Yes, other states require some coverage of state and local government at the college level as part of one course or another. I think that may even be part of the language spelling out gen ed requirements in California. But I can guarantee you that kids growing up in California (and most other states) do not say a pledge of allegiance to the state flag as they do here. It’s a lot.