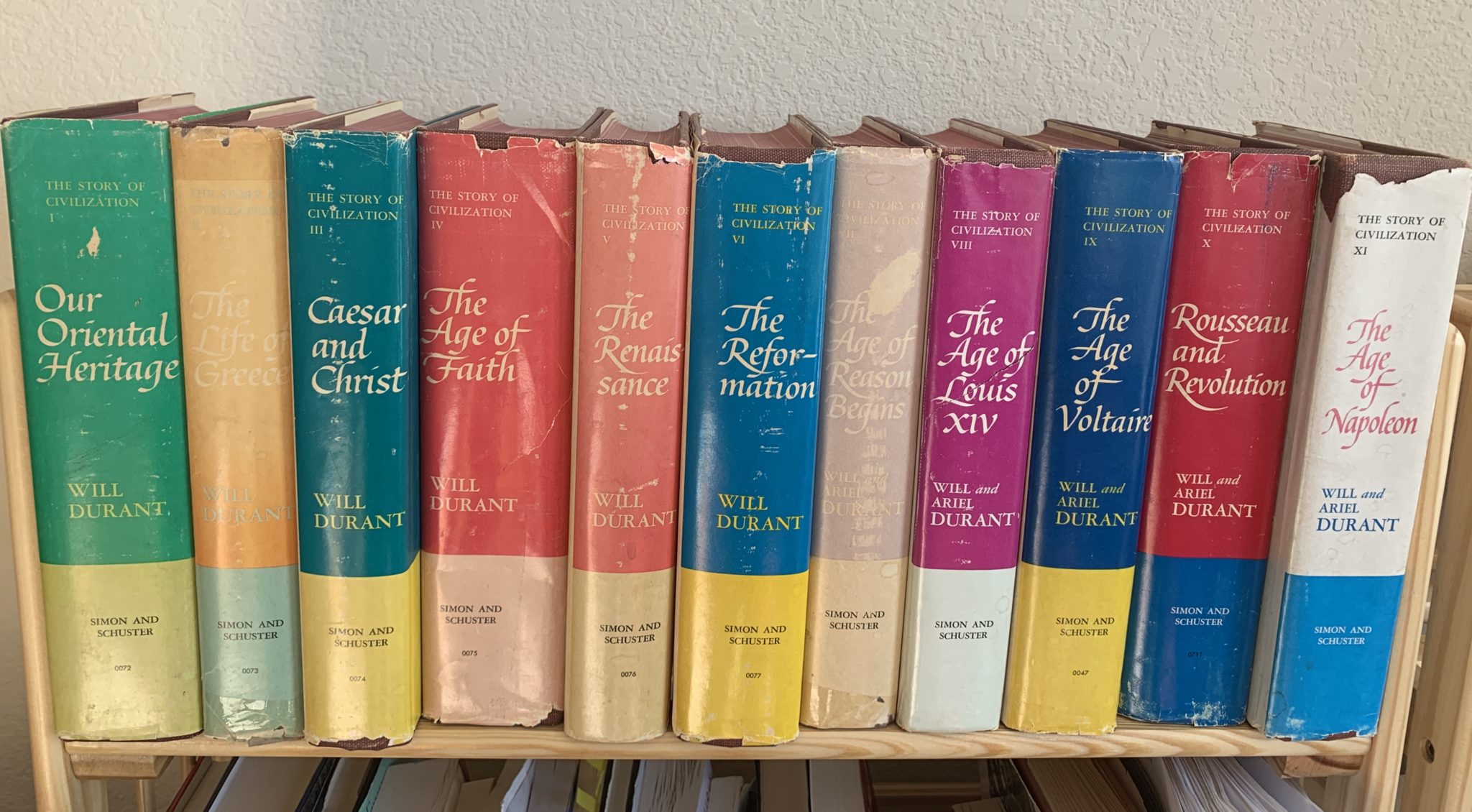

The full eleven volumes of The Story of Civilization, Will and Ariel Durant’s popular history of (mostly) the “Western world,” take up exactly 22” of shelf space, fitting perfectly on the top shelf of one of the unfinished pine bookcases I bought for my apartment during my VAP year at Tarleton State University. Now those shelves are ranged against a wall of my bedroom (bookshelf creep in my house is real, y’all). There stand the Durants, serene and complete, as I make my way through their pages.

A motley eleven-volume set of Will and Ariel Durant’s *Story of Civilization*

In her indispensable book The Making of Middlebrow Culture, Joan Shelley Rubin situates the career of Will Durant as illustrative of the craze for the “outline” approach to knowledge, exemplified by H.G. Wells’s wildly popular Outline of History. Though Rubin focuses on Will Durant’s solo production, The Story of Philosophy, her observations about the success of that work generally hold true for The Story of Civilization

. These single-volume or multi-volume combinations of command and concision – purportedly comprehensive knowledge, systematically arranged and neatly packaged – provided assurance to their readers that everything they needed to make sense of the world (or some particular aspect of it) could be found within the covers of these books. To have them was to have at one’s fingertips a whole field of understanding – a comforting suggestion of general command in an era of increasing intellectual specialization.

For many, simply possessing these books was assurance enough. In the same way that encyclopedias served as a marker of middle class respectability and by their very presence signified an educated household – a function wonderfully discussed in The Hidden Injuries of Class by Jonathan Cobb and Richard Sennett – the full set of the Durants, ranged neatly on a shelf, testified to the learning and sophistication of the household in which they were proudly displayed.

Much like encyclopedias (or a full set of the Church Fathers, or Eliot’s “five foot shelf of books,” or Britannica’s “Great Books” series), the Durants were displayed side by side more often than they were read cover to cover. This was tangibly demonstrated to me as I made my way through the first volume of the set I purchased. Due to a printing error, an entire quire of pages was missing from the volume. The paging jumped from page 30 to page 63, proceeded from there up to page 92, and then repeated pages 63-92 before moving on in sequence for the rest of the volume. I wrote to the booksellers right away and let them know I’d received a misprinted volume as part of the set, and they very kindly posted a replacement volume right away.

That’s the tricky thing with “full sets” of the Durants – there were so many complete sets sold new, so many volumes in circulation, that a used “set” might comprise books from several different printings. Indeed, my faulty first volume came from the twenty-fifth printing, while my fair second volume came from the twenty-second printing of the work. The very tattered dustjackets for my set also come from a range of different printings, and they don’t always match the book they are protecting, suggesting that used booksellers probably access to a fairly steady supply of “replacement parts” for full sets of Will and Ariel Durant.

Will Durant lounging on my Bali bed in Tulum.

While I was waiting for my replacement volume to arrive, I decided to proceed through the volume I already had. Indeed, I took it with me as a beach read on a vacation to Tulum earlier this summer, leaving its tattered dustjacket behind. As I made my way through the volume, I came upon a few pages that had not been completely cut along the top edge. I found myself wondering if the original purchaser of book had ever read far enough into it to notice its printing gap, never mind its binding flaws. Perhaps the mere possession of the work, spine unbroken and pages unread, met the purposes of its first owner. And how many times had it been sold and resold since then as part of a set, without its purchaser ever discovering that it wasn’t complete? It’s impossible to say. This particular volume from the twenty-fifth printing can be no more than 53 years old – I say that because the twenty-second printing shows a copyright date of 1966, and (much as I hate math) I can say with some confidence that twenty-two comes before twenty-five. (No, I don’t want to hear about a mathematical universe in which that might not be true.)

A few pages still attached along the top edge.

Anyhow, after bumping around the world for some fifty-odd years, give or take – making this book about the same age as yours truly – this volume came into my possession and I did what no one had apparently done before: I read it.

But I’m not the only historian to have read one or more volumes of the Durants. In fact, when I posted on Twitter back in the spring that I was reading through these volumes, I heard from a few scholars who mentioned that they grew up in households with a set of these books and that reading these books at some point in their formative years had a significant influence on their eventual decision to study history or adjacent fields.

The reception history of The Story of Civilization is of interest to me. I can’t say how much of it will make its way into my book. But this massively popular and widely circulated set of books purporting to offer a comprehensive history of the (Western) world probably had a significant influence on popular ideas about what “civilization” means or can mean, and – judging from the responses I got on Twitter – may very well have had a formative influence on generations of historians. From a quick search of JSTOR, I can tell you that only a couple of the volumes were ever reviewed in scholarly journals, and in almost all of the reviews the Durants’ work was panned. But that doesn’t mean the work was not influential, even among scholars, at least in their formative years.

So, as a way into this subject, I ask:

Did you grow up in a household with a set of the Durants? Did you browse through a volume or two? Did you read the whole set? Did you acquire them in adulthood and enjoy them later in life? Have they ever been on your “to read” list? How did they get there? Are they on your “to read” list now?

I would love to hear from readers here in the comments. Or you can @ me on Twitter. (I am between jobs right now, so email is probably not the best way to reach me at present.) Even if these volumes were only ever decorative in your experience, I’d love to know what that decoration signified.

If 22” of shelf space in your childhood home was set aside for Will and Ariel Durant, what did that mean for you? What books were ranged above them or below them or alongside them? What place did they hold in your imagination? What place do they hold in your memory?

10 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I read through three of the volumes, Age of Faith, Age of Reason, Rousseau and Revolution. At that time (I was in college, these were too much to think about before that) I thought I was knee deep in the Truth Behind the World. I still have flashbacks to Age of Faith–it served to fire my interest in professional history–more properly Religious Studies. The picture of a hermit stuck in a cave dreaming about naked women, or one on the top of a desert pillar with maggots on his wrist still drifts past. I inherited the set and it’s still on the shelf, untouched since those days long ago.

In high school, the third volume, Caesar and Christ, was part of the recommended reading for an academic quiz bowl-type competition I was in when the theme was Ancient Rome. I was the one on the team who was assigned to read it, and I remember being quite taken with the dramatic nature of their writing–I hadn’t read much history outside of textbooks and enjoyed it very much.

Well yes, there was a time I coveted these books. My populous family had few books around, though we did have the Britannica collection. My best friend in high school had 4 or 5 of the Durant series. There was something mesmerizing about them…the bold colors, the big titles, the promise of knowledge, albeit in thick tomes but yes, that was to be expected, it had to be that way! I finally started collecting these in college (having become a used book junky) but delaying my reading till I had time. Somewhere in my thirties I finally opened them, admittedly somewhat jaded by my college experience as to what a “valued” historical work constituted. I was saddened to find they were nearly unreadable…the style seemed peripatetic, chronologically anchored, literally “one thing after another” in a frantic effort to include all the big historical names and events as though shoveled into and delivered in wheelbarrow. I still have about half a dozen of them but have no urge to crack them open. On the upside, I’m halfway into Sophia Rosenfeld’s, Common Sense and find it terrific.

Thanks for these great comments — I am hearing from so many historians and general readers who found this set formative or useful in some way. The style of the writing is something that either delights or annoys, and for the most part I find them engagingly written. I’m still in the middle of it all — I’m not a quick reader anyhow, and these are not a quick read. But I have been surprised to learn how many people, from baby boomers to millennials, have in fact read the whole set or parts of it — often when family members from an older generation had the books prominently displayed but didn’t themselves use them much if at all. Never underestimate the draw of a hardbound series for a supremely bored kid at grandma’s house!

I’ve never read any of the Durants’ books in full, but as a student of Britannica’s publications I’m following this “story.”

FYI: I’ve intensely read many volumes in my Britannica *Great Books* set, but I still occasionally run across a volume with attached pages or printing abnormalities. (When I say intensely, I’m an underliner and margin writer, so my books are virtually useless to the next reader—unless they are speedy whizzes with erasers.) – TL

I am not the first to note that for many, many years, they were a standard membership offering of the great book supplier to the mass middle class, the Book-of-the-Month Club. Although fashionable to deride them at times, as others have noted they were introductions to reasonably serious history for many people growing up. They were in my parents’ house.

Apart from the books in these series i also read one or two of Will Durant’s books on philosophy. They are more than adequate as i recall even if for general audiences of a serious sort.

I am glad they are receiving something of a reasonably respectful appraisal here.

In high school I checked out volumes from the public library, beginning, probably, with the The Age of Reason Begins. (The Age of Faith was too fat, and anyway I wanted an overview of knowledge.) From my Time magazine subscription, I learned that Will Durant was involved with the radical worker education movement in NYC during WWI, that his wife’s name, Ariel, was self-selected (gasp), and that they had been collaborating for decades on the series and were now very old but still writing. It was all very inspiring. Later, I learned their life’s work was middle brow culture for the consuming masses (sigh).

In TIME (22 July, p.38), they end a story on Netanyahu (who grew up partly in US), says this of LESSONS OF HISTORY (by Durant): “”Lesson No. 1, history does not favor Christ over Genghis Khan. OK. Lesson No. 2, in general I would say, big numbers have an advantage over small numbers. That’s bad news for us. Then he says, at a certain point, sometimes the power of culture and leadership overcome limitations of geography. And perhaps the new country of Israel, is an example of that, how we overcome the odds of history. . . . The strong survive. Strong and smart.”

No comment on the content, on the Durant connection.

Did not have Durant volumes growing up or look at them later. Did glance at Durant’s time as an anarchist intellectual, fascinated with Darwinism (as I recall). He was also connected with Socialist Party in the pre-war days – I think he felt the two might be complementary.

While I didn’t grow up with the Durants on my shelf, I did get them as gifts when I was an undergrad. I had initially chosen to go into history because it involved very little math. I was extremely lucky because I ended up falling head over heels for the discipline.

My grandfather had originally given my father the History of Civilization collection when my father was in undergrad and then grad school. One of his professors apparently cribbed entire sections from The Life of Greece and went pale when he realized my father was reading it – and therefore understood that some sections of the talk were word-for-word unattributed quotes from Durant. The professor had apparently been passing it off as his own for years on yellowing handwritten paper notes.

When I got the Durants, it completely changed how I viewed history. The Life of Greece, the first volume I read, dedicated *maybe* 20% to political history. Through this I realized how myopic my understand of the discipline had been. I learned about law, poetry, sculpture, and the mundane but fascinating aspects of everyday life. In volume 3, Christ & Caesar, I learned about how Roman law subjugated women and read with interest the Durants’ reframing of Augustus’ attempts to impose ‘morality’. I’d heard about these before, but hadn’t understood them as part of a broader history of the legal rights of women. Doubtless the frequent discussions of the history of women – the first I’d come across it – are largely thanks to the efforts of Ariel Durant.

While I often celebrate that she became the full co-author of History of Civilization partway through the series, I confess that I remain troubled by her age when they met and married and the fact that she was his student (15 years old) at the time – though he left his post in order to marry her. However, this is something I discovered far later.

One of the major takeaways from the books was that history can and should be written in exquisite prose, even if the topic doesn’t (initially at least) seem like something easily translatable into popular enjoyable prose for the general reader. The Durants and Gibbon remain my North Star as regards historical writing.

One day I’ll go back and do a full reread sometime. They’ll always have a prominent place on my bookshelf.

I read The Story of Civilization, Vol. I-IX in high school fifty years ago. I’ve remained a voracious reader, it’s not the type of thing you give up, with a special interest in history. I never took the suggestion from Durant that I was reading all I had to know, or that there were definitive judgments being made. Instead, my curiosity was constantly piqued and even before finishing those nine volumes i was making my own excursions into topics, some of which would become favorites. But I think now, and I had an intuition of it then, that one has to get an overview, and a surface acquaintance with the whole course of history (or at least through the mid eighteenth century, which is where I dropped off) before one studies any particular period, state, or movement. To a young person interested in history I would recommend that he read a universal history first. I’d recommend Durant, although there may be, there must be, several good ones. I haven’t looked for another, because I think one only reads that type of work once. I know I couldn’t read another universal history. I also believe that a good historian will send you to original sources, and many of my first readings in these were passages quoted in Durant. Reading The Story of Civilization I also read my first Greek tragedy, French comedy, Platonic dialogue and the list could go on.

And there are some wonderful moments. The best summary of a tragedy I ever read, Racine’s Andromache: ” Orestes loves Hermione, who loves Pyrrhus, who loves Andromache, who loves Hector, who is dead.”

Finally, I don’t know any truer test of the classic than that it continues to find new readers in successive generations. And maybe that’s the case with Durant. If in fact those volumes are being read.