Will Durant’s The Life of Greece, the second volume in the “Story of Civilization” series, was published in 1939, a grim year for “Western Civilization.” Despite – or perhaps because – the book was such a popular success, it was reviewed in a handful of academic journals.

Two reviews of this volume nicely illustrate the camps into which academic readers of Durant seemed to fall: either they lauded him for his ability to bring to the distant past a sense of immediacy and vividness for the general reader, or they lambasted him for his hamfisted handling of historical argumentation and historical facts.

One review, in praising Durant the popularizer, critiques the social sciences of the time for the arcane interests and esoteric specialization of scholarship content with investigating minutiae of interest only to other scholars. But that critique of scholarship for its dry-as-dust specialization is framed in the way that such critiques of scholarly research in the humanities are often framed today: in studying esoteric subjects that are of no broad relevance, humanists are betraying a duty to consider not just the Big Questions but the Big Culture(s) that truly matter in the long sweep of history, and nothing matters as much as Western culture. “It is eminently respectable to spend half a lifetime in the study of some insignificant tribelet having no demonstrable connections with the culture of the Western world,” wrote Howard Becker in the American Sociological Review, “but preoccupation with things Greek is thought to be direct evidence of a sickly estheticism or a failure to concentrate on ‘genuine research.’ Year after year we turn out dissertations establishing correlations between the number of bath-tubs and the amount of juvenile delinquency in Oskaloosa without feeling at all apologetic. Why? Because of our rampant ‘raw empiricism’ and lamentable lack of historical sophistication.”[1]

There’s a lot going on here. There’s the dismissive sneer at anthropological or ethnic studies, particularly those focused on cultures that are not part of the grand sweep of “the West.” There’s the eye-rolling jab at “empiricism” that contents itself with addressing minute questions whose answers may be quantifiable but are not qualitatively important.

All this is the backdrop to a review of several works among which Durant’s is included: Pearson’s Early Ionian Historians, Botsford and Robinson’s, Hellenic History, Birt’s Von Homer bis Sokrates, Jaeger and Highet’s Paideia, Bonner and Smith’s The Administration of Justice from Homer to Aristotle,Jaeger’s Demosthenes, and Nestle’s Der Friedensgedanke in der antiken Welt.

That’s pretty heady company for a bestseller aimed at a general audience. In Becker’s view, though, Durant holds up very well. However, for this reviewer, praising Durant’s work serves as a way of disdaining scholarship that relies on more specialized language. “This writer, for all his popularization, is not to be sneered at in the manner all too common among the professorial guild. Granted that he does not soar so high that only those equipped with the oxygen outfit of monographic research can follow him; granted that he occasionally smirks at an audience eager for scandalous tidbits; granted that he sometimes indulges in epigrams that verge on the Broadway wisecrack—but should a few venial sins altogether bar him from salvation? The present reviewer has read a great many surveys in this field, and he says without reservation that Durant has no superior where the intelligent general reader is concerned. Most of us, after all, are general readers, no matter how many academic baubles we have pinned to our names.”[2]

That’s pretty heady company for a bestseller aimed at a general audience. In Becker’s view, though, Durant holds up very well. However, for this reviewer, praising Durant’s work serves as a way of disdaining scholarship that relies on more specialized language. “This writer, for all his popularization, is not to be sneered at in the manner all too common among the professorial guild. Granted that he does not soar so high that only those equipped with the oxygen outfit of monographic research can follow him; granted that he occasionally smirks at an audience eager for scandalous tidbits; granted that he sometimes indulges in epigrams that verge on the Broadway wisecrack—but should a few venial sins altogether bar him from salvation? The present reviewer has read a great many surveys in this field, and he says without reservation that Durant has no superior where the intelligent general reader is concerned. Most of us, after all, are general readers, no matter how many academic baubles we have pinned to our names.”[2]

The figurative language is interesting here. The reference to soaring so high that one needs an “oxygen kit” seems to be an up-to-the moment reference to technological advances in (military) aviation. This would have been a particularly striking image, I think, near the beginning of World War II. No one needs such “special equipment” to read Durant, special equipment that includes “academic baubles” – advanced degrees. Instinctive aversion to Durant’s rollicking narrative and his success represents so much “sneering” by “the academic guild.” Durant is here envisioned as the champion of the common man against the elite.

An explicit denial that critique of Durant springs from mere reflexive defensiveness and “guild” solidarity concludes a scathing review of The Life of Greece

written by M.I. Finkelstein. “These questions are raised from no narrow ‘guild’ interest, nor as an attack on popular history,” Finkelstein writes at the end of a blistering review. “Quite the contrary. There exists a genuine need for popularization which will be neither vulgarization nor Philistinism. An accurate portrayal of the material and intellectual forces of Greek society in all their ramifications and interconnections can be more exciting than the cheap romanticizing of a Will Durant – and certainly more vital and socially useful.”[3]

The “cheap romanticizing” Finkelstein called out in Durant was not just a stylistic gesture but an intellectual flaw. Finkelstein singled out what he saw as Durant’s conception of race and races as having set characteristics that endure through history, an “essential sameness” such that one can discuss “Oriental autocracy” and “the rugged North” as if these were fixed and immutable factors in shaping history. This is romanticism and romanticizing in a Herderian sense, and Finkelstein is not having it. Durant’s thinking on the constant of race is pernicious not simply because it is a bad and lazy explanation for the past but because it lays all the weight of historical change on great men. “Racism is naturally accompanied by the notion that it is the leader-hero who molds history,” Finkelstein writes. “Mr. Durant reveals a deep distrust of democratic forms and a contempt for the ‘mob.’”[4] Thus, rather than writing a work that gives the common man an intellectual foothold among the elites, Durant’s entire argument upholds and undergirds the consolidation of power and authority in the hands of the few rather than the many – also a striking argument to make in the early years of World War II.

Finkelstein has little patience for Durant’s reputation or his reach among general readers, educated or otherwise. “Mr. Durant has read fairly widely,” Finkelstein writes, “but not enough or with sufficient discrimination to avoid innumerable errors or to be able to distinguish between a wild guess and a sober judgment. Apparently the main function of his research and learning is not to enlighten but to impress the uninitiate (with the assistance of reviewers in the daily press who know next to nothing about Greek history).” No wonder, then, that Finkelstein felt it necessary to conclude his review with a disclaimer that he was not here simply speaking up for “the guild.”

Instead, Finkelstein’s review includes an explicit indictment of America’s system of education. He began with a rhetorical defense of the aims of professional historians.

The Life of Greeceis a best seller. The challenge therefore has two aspects. Is the study of history to be nothing more than a series of perversions of the past, designed to hoist public opinion onto the band wagon of the moment? Or is it a scientific discipline, the search for an understanding of the historical process, motivated by a deep-rooted interest in human welfare to be sure, but free from any restrictions imposed by momentary political pressures and whims?

Here is a paean to empiricism, to objectivity, to inquiry that is humane in interest but not presentist in motivation or approach.

But then comes the critique:

Secondly, what is wrong with our educational system when more people learn ‘history’ from one book by Will Durant, aided and abetted by the press, than from a whole year’s output by all the professional historians in the country?

Why aren’t more people reading the work of “the professional historians”? It must be because something is wrong with “our educational system.” But doesn’t that system include those very historians? And there is so much vituperative ire reserved for “the press” as an agent of public mis-education. Imagine what the outcry would have been if Durant had had a regular column in The New Yorker. (Durant did, in fact, have a syndicated column running in newspapers in the 1920s, which helped very much to make his byline a household name before he published a single volume of this series.)

Will Durant’s book was not the first work of popular or popularizing history to receive critical attention, positive and negative, from scholarly reviewers writing in academic journals, and it certainly won’t be the last. Indeed, these two antithetical perspectives on a runaway best-seller nicely stake out the polarized extremes of both the academic reception of popular history and the academic perception of scholars’ own role in shaping popular views of the past.

_____________

[1]Howard Becker, “Review,” American Sociological Review

5, No. 2 (April 1940), 287.

[2]Becker 288.

[3]M.I. Finkelstein, Review, Political Science Quarterly

56, No. 1 (Mar. 1941), 129.

[4]Finkelstein 127.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

What seems to be missing from Finkelstein’s review is almost standard indictment of, or nod towards, professional writing. He puts pressure and responsibility on the reader—to be more educated, to appreciate the subtleties of academic writing. Becker speaks to writing style in his reference to the empiricism of specialists, which apparently makes them hard to read—as a factor apart from style.

Also interesting is the category of “intelligent reader” as someone distinct from those who appreciate or desire academic writing. This intelligent reader is of course very literate—above the middlebrow reader of Rubin’s work. The former seems to have the ability to understand academic subtleties but just want some easier-to-read/digest non-fiction and history that lets them casually read in their subject area. The intelligent reader is a tweener between academics and the middlebrow.

Anyway, great stuff. I love reading reviewers. They open up so much about academia, literary worlds, literacy, reader/writer expectations, etc.

Tim, thanks for this comment. What I found so fascinating about both of these reviews is how they nicely encapsulate the sorts of moves that academic reviewers make frequently when confronted with a popularly successful work of history that “shouldn’t” be as popular as it is. Is the writing style engaging or off-putting? Does the popular success of the author speak to the out-of-touchness of “the field” or the easily-led-astrayness of the reading public? Both? Are the misstatements or misapprehensions in a work of synthesis qualitatively different (less or more egregious?) than those in a work of original research? Is it possible to write a scathing review of a popular best-seller without sounding petulant and envious? Is it possible to write a ringing endorsement of a popular best-seller without throwing academic historical writing under the bus?

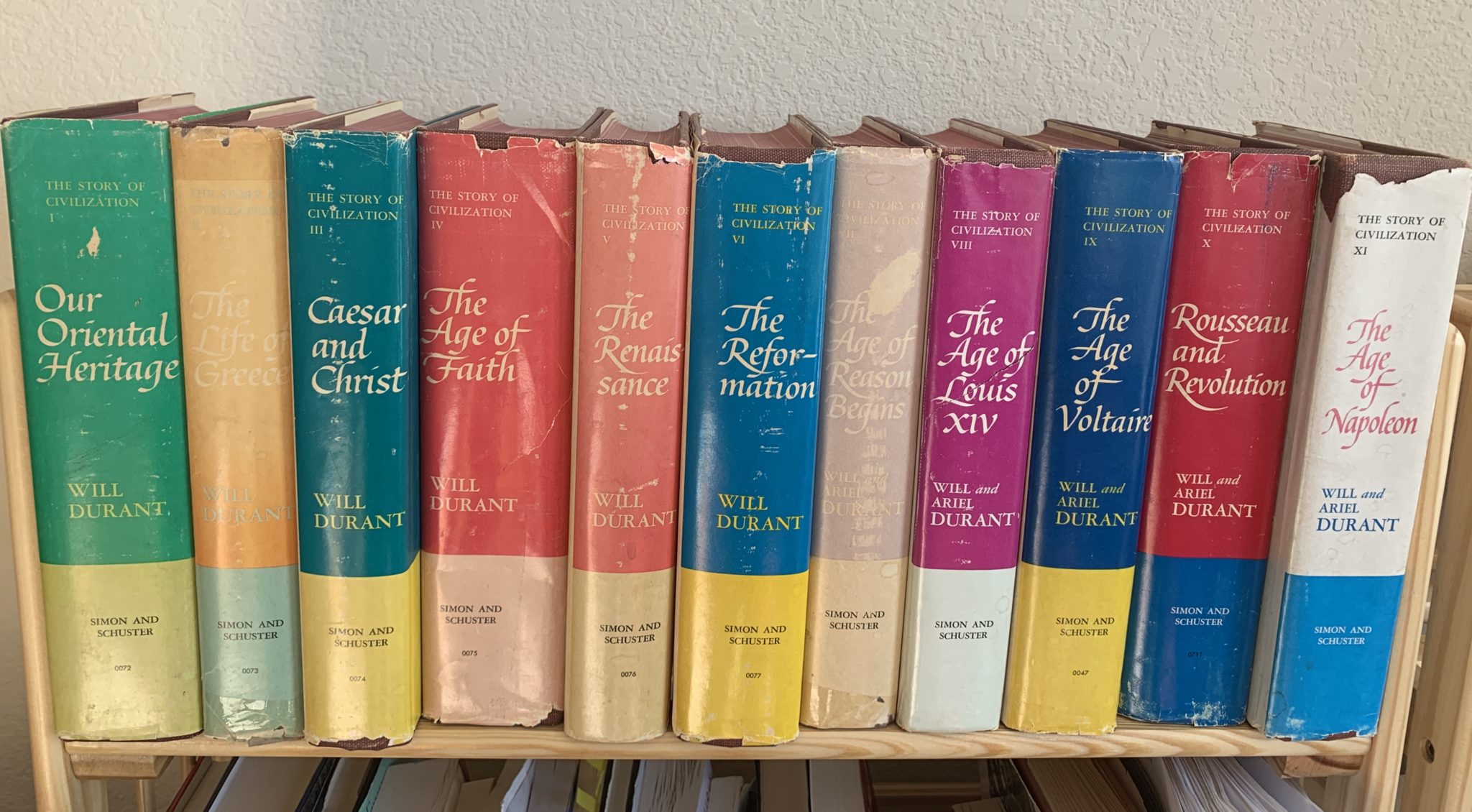

These questions and debates come up repeatedly. Who can lay claim to the title “historian”? That was the subject of a recent donnybrook on history twitter (I didn’t participate, for once). But there were many people, then and now, who consider Will and Ariel Durant to be “historians” and this popular series to be a work of history — obviously a work of synthesis, but a reliable enough narrative framing of a huge chunk of the human past through which people can be reasonably introduced to a subject in which they might make further inquiry. Should people consider Will Durant a historian? Technically no, even the positive reviewer suggests. But judging on the caliber of the work, why not? The negative reviewer, on the other hand, says no way.

The Finkelstein review is interesting because he takes Durant to task for his seeming suspicion of/aversion to “the masses,” while at the same time lambasting the popular press for purportedly leading the (implicitly ignorant, in need of guidance, and therefore probably dangerous) masses astray by lauding Durant’s work. Finkelstein is every bit as distrustful of “the masses” as he accuses Durant of being, and the repeated digs at “the press” in his review sound ever so slightly envious or resentful, as if “the press” is failing in its job because it’s lauding the Durants of the world instead of the Finkelsteins.

That resentment touches upon another current topic among historians: What connections should reviewers draw between Jill Lepore’s writing in The New Yorker and her recent work of synthesis, These Truths? (Not that the masses read The New Yorker — a point often raised to prove that Lepore’s writing is not really popular.)

That doesn’t mean the critiques of her work are misplaced, but why does it seem impossible for academic historians to pull off these critiques without a sneer or a snarl or a dig about The New Yorker? I know academics in real life who have said, almost in so many words, that they’re smarter than Lepore is and their work/thinking is more rigorous than hers and she has just been lucky and just clever enough to stick with what’s “trendy,” etc, etc, etc. (I know women in academe who don’t like Lepore’s work, but I have yet to hear any woman in conversation claim, as some men have, “She’s really not that smart” or “She’s really not that good a historian.”)

Anyway, the problem of what to do with sweeping works of historical synthesis written in an engaging style whose occasional errors seem like howlers to specialists but will go unnoticed with general readers — this is not a new problem for academic reviewers. There are a few rhetorical moves to make, as exemplified in the above reviews: blame the discipline for being jargon-riddled and inaccessible, blame “the press” (or, these days “the internet”) for leading the history-deprived people astray, blame the education system for failing to teach students real history so that they are susceptible to appealing but not reliable narratives, dismiss the successful author as simply the master of a riveting style that can mask or paper over egregious gaps in knowledge, invoke the speed with which the writing has been accomplished as a necessary correlative to a troubling carelessness in execution, etc, etc, etc.

In short, there are only so many ways you can say, “This book should not be selling as well as it is” or “If this book is selling as well as it is, there must be a problem with [fill-in-the-blank].” And while this is sometimes framed as “our” problem, it’s never the reviewer’s problem specifically.

It would be interesting to compare reception of Durant with reviews of contemporaneous popularizing works by university-based historians, who presumably were methodologically and conceptually “up-to-date.” Charles Beard and Mary Beard’s *History of the United States,* for example, was an enormous best-seller, with a similar grand synthetic ambition, maybe in fact even more ambitious than Durant’s dedication to assembling the “facts” into a coherent story, but presumably grounded in the archival work that both authors had done for a longtime before their book appeared in 1921. According to a recent biography of Charles Beard (•Charles Austin Beard: The Return of the Master Historian of American Imperialism* by Richard Drake, Cornell University Press 2018), the Beards’ book played a critical role in promoting the idea that the United States was a distinct civilization. I would suspect that their book was exemplary work for Durant. Finkelstein’s zeroing in on the problematic of Durant’s use of race as a basic explanatory factor would be pertinent in that although from the perspective of the early 21st century, the Beards’ approach to race is entirely problematic, their economic and institutional conception of “civilization” rejected both Herderian understandings of “nation” and “people” and the positivist approach to historical study so widespread in the second half of the 19th century and found in abundance in the work of Ulrich B. Phillips. My guess would be though that Hippolyte Taine was a more important predecessor than Herder for Victorian and post-Victorian discussions of the nation in the United States. U.S. publishers translated Taine’s books on the ancient world, Renaissance Italy, the Dutch Republic, France, and England. These editions went through multiple printings, some remaining in print for decades, suggesting well they sold in the United States. Curiously, there was less interest in the United Kingdom. Taine reminds us of the influence of positivism on cultural thought, an influence distinct from and antithetical to Herderian romanticism. Simple-minded and reductive of course, but in a different way. Durant’s sin as an amateur historian was placing himself in a tradition that remained popular but had become bankrupt in the academy. Perhaps a sin shared by writers like David McCullough, whose works are read more widely than any of the scholars whose work appears in the •New Yorker* or comparable journals today. Surely well-known scholars and scientists have long published regularly in major periodicals that gained a reputation for “quality”–the *North American Review,* the *Atlantic,* *Harpers,* long before the *New Yorker.* Their participation might have been (and remains?) essential for particular journals establishing a profile as serious and distinguished rather than merely “popular.” TED talks have likely become an even more important way of promoting scholarly perspectives among those who believe their opinion counts for public decision making. To the degree that scholarship is actually about methodological and interpretive debate, it makes sense for a scholar to get her ideas out into the world so one’s intellectual opponents don’t shape the larger terrain for reception of the competing ideas at play in a field. The Beards certainly understood that their interpretation of U.S. history was contentious. I wonder the degree to which Durant understood, or was even aware of, the many, many debates that allowed him to tell his universal story. Or did he assume that getting available information out was a difficult enough challenge and the highest priority for developing an educated citizenry?