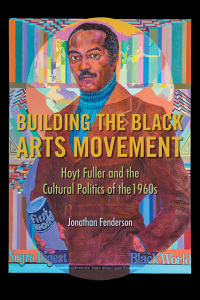

The Book

Building the Black Arts Movement: Hoyt Fuller and the Cultural Politics of the 1970s. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2019

The Author(s)

Jonathan Fenderson

A revolutionary aesthetic for all the fine arts is essential. These italicized words were part of Robert Chrisman’s essay, “The Formation of a Revolutionary Black Culture,” an entry into an early issue of The Black Scholar. For Chrisman, the burgeoning Black Arts Movement offered a chance to continue to blend radical African American art, politics, and culture in a way that would be most beneficial for the African American community. Chrisman, however, was also part of a small cadre of African American editors who played a vital role in institution building during the Black Arts Movement era. Hoyt Fuller’s leadership at Negro Digest—later to become Black World—provided an opportunity for leadership that fostered debate and dialogue for artists, writers, and intellectuals across the Black Diaspora.[1]

In Building the Black Arts Movement, Jonathan Fenderson shows how Fuller’s position as an editor of arguably the most popular periodical during the 1960s and 1970s dealing with the fullness of the intellectual and cultural Black experience was instrumental to the intellectual and cultural history of the era. For Fenderson, Fuller was without question “a central architect of the Black Arts movement, whose work in a number of areas would shape the course of African American arts and letters” (4). At the same time, Fenderson demonstrates that Fuller’s tenure at Black World was a prime example of the contradictions within the African American community—much of which has been subsumed by the need to fight for freedom during the Civil Rights era but coming to the forefront in the 1970s. The problems of “class, capitalism, and the American marketplace” were, for Fenderson, not only critical roadblocks to greater success for Fuller, but indicative of the kinds of structural issues that ultimately doomed radical African American letters in the 1970s (12).

Remember, Fuller’s tenure as editor of Negro Digest/Black World was under the larger media umbrella of Johnson Publication Company, owned and operated by John H. Johnson. Building the Black Arts Movement details the friction between Fuller and Johnson—a friction caused by Johnson’s Cold War liberalism and belief in shying away from the contentious politics of the day in his mainstream magazines, Ebony and Jet, versus Fuller’s embracing of a radical critique of American society. Part of this was born out of how the two men viewed the African American experience itself. For Johnson, advancement in American society as an African American was certainly possible, if one worked hard. Thus, he insisted on highlighting African American firsts in his magazines. For Fuller, however, it was more important to think of the African American experience as couched within the larger Black Diaspora. There was no American exceptionalism being written about in the pages of Negro Digest/Black World under Fuller’s tenure.

However, Fuller fought to showcase a vibrant, rich world of Black letters that, from 1961 until the end of the magazine in 1976, was the centerpiece of the Black Arts Movement amongst periodicals. Fuller’s travels to Africa allowed him to build relationships with intellectuals and artists all across the Black Diaspora, many of whom were featured in the pages of Negro Digest/Black World. Building the Black Arts Movement

could easily have been titled Building Black Intellectual Institutions, as Fuller was instrumental in the rebirth of Negro Digest as an intellectual periodical in 1961, as well as helping found the Organization of Black American Culture, or OBAC in Chicago. Recent works in African American intellectual history—2011’s The Challenge of Blackness, 2018’s Set the World on Fire¸ and 2017’s Remaking Black Power come to mind—all show the critical work done by intellectuals in the African American community who also devoted considerable time, effort, and energy to creating intellectual and cultural institutions. The Challenge of Blackness, especially, is a useful read alongside Building the Black Arts Movement. Both Derrick White’s book and Fenderson’s point to the importance of place in building intellectual institutions—for Derrick White’s Institute of the Black World, Atlanta as a city (and as an idea) was instrumental in that institution’s existence, while the economic and political power of Black Chicago was a unique and arguably necessary backdrop for the work done by Fuller.

Both books also work in concert because they both showcase an intricate understanding of the radical Black experience of the 1970s. The specter of conservative backlash hangs all over Building the Black Arts Movement, ultimately being an important factor in Black World’s demise in 1976. The weakening of African American institutions during the 1970s—concurrent with the collapse of the Black Panther Party, infighting amongst Black intellectuals over a Marxist or Black Nationalist approach—was best exemplified by the fall of Black World in 1976. Ultimately, Fenderson’s book goes a long way toward showing how the 1970s were both a vibrant moment in African American intellectual history, and a dire turning point.

Briefly, it is important to discuss how Fenderson uses sources and theorizes about examining the past. The dive into Fuller’s personal life—specifically his sexual history and his struggle with a gender identity that didn’t fit neatly into modern ideas of “queerness”—should be read by graduate students and professors alike for thinking about the silences in archives. Fenderson argues that “studies of Black sexuality (and the social construction of gender) necessitate historicization” (149). In other words, when trying to get at the whole backstory of someone as complex as Fuller, we need to recognize the importance of precision of language and analysis.

Building the Black Arts Movement is a necessary examination of the Black intellectual world of the 1960s and 1970s. Thinking about this book in light of the recent news of the acquisition of the Ebony/Jet photographic archive is illuminating, because it reminds us of the importance of Johnson Publications to the chronicling of African American life. More work is being done on this—James West’s works on Ebony

and Lerone Bennett are also important reads. But Jonathan Fenderson’s book is a masterwork of African American intellectual and cultural history, bringing to light a man whose name should be mentioned more often in the histories of contemporary America.

[1] Robert Chrisman, “The Formation of a Revolutionary Black Culture,” The Black Scholar, Vol. 1, No. 8, June 1970, p. 9.

0