“That’s one small step for [a] man, and one giant leap for mankind.” – Neil Armstrong, July 20, 1969

I was born before humankind set foot on the moon.

That dates me, as it dates everyone else who is fifty years of age or older as of July 20, 2019.

More than dating me, though, that demographic fact situates me and all who are close to my age in the middle of what is – I would argue – an historical epoch whose enduring significance none of us will be able to fully grasp, for we are still in the middle of its unfurling.

During the first week of teaching, every semester, I always ask my students about the problem of periodization. I always ask them to think of various ways that we could (heuristically, artificially) divide the epochs of human history, never mind American history.

Rarely do my students mention the detonation of the first atomic bomb as an epochal event, though I would argue that “the atomic age” is an apt periodization for all of human history since 1945. Certainly, no one to date has mentioned “the Industrial Revolution,” never mind “the Anthropocene,” as an epochal moment or even an epochal era.

But on more than occasion, one student or another has suggested the moment when Neil Armstrong first set foot on the moon.

It’s not just because I can claim antiquity in relation to that ephemeral moment that I believe this is a useful divisor for Before and After.

Rather, here is what I tell my students, whenever one of them volunteers this moment as an epochal pivot in the history of humankind:

As far back as historians can go, and even farther back than that, cultures all over the world have told stories about the moon – about its origins, or its divinity, or its influence on human affairs. As far back as history goes, as far back as mythology goes, people all over the world have looked to the sky and looked to the moon and made it part of the story of who they are and what they know and what they believe. Every human culture that has ever existed, as far as we know, has in some respect reckoned with the moon as a fixture in the realm of human or heavenly knowledge. Every culture has stories about the moon. It is part of our collective memory and our diverse faiths. It was a place or a person or a presence accepted and believed in, though never touched.

On July 20, 1969, humankind touched this nearest object of its immemorial veneration.

We all still live in the penumbra of this moment, whether we chanced to be born before or after it happened.

But it happened. After thousands of years of human faith and longing, the things that were believed became the things that were seen. That is an epochal moment, still worthy of our contemplation and our awe.

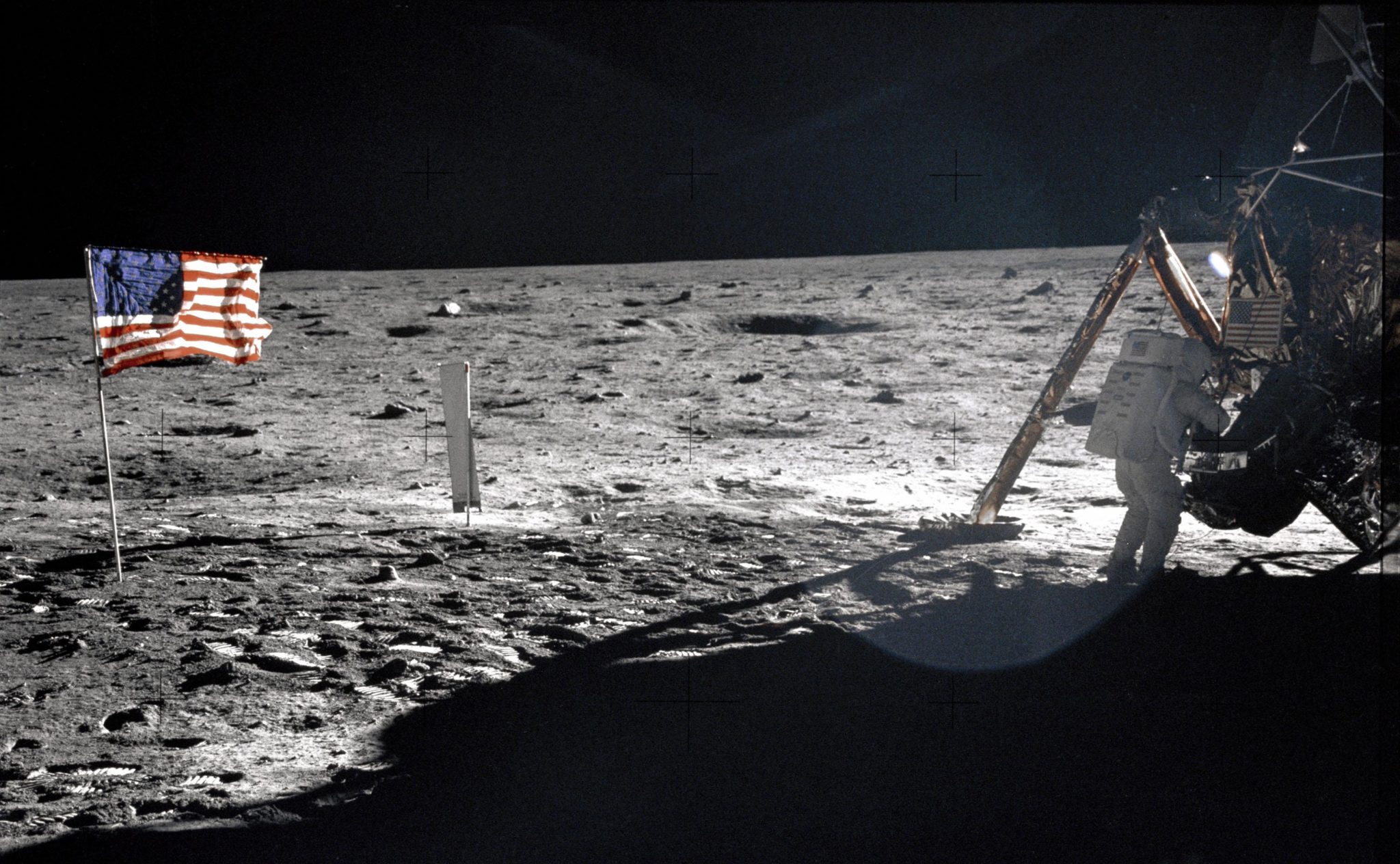

Apollo 11 Commander Neil Armstrong working at an equipment storage area on the lunar module. This is one of the few photos that show Armstrong during the moonwalk. Click image to enlarge. Credits: NASA

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Oh, man has invented his doom

First step was touching the moon

– Bob Dylan

Sad to say I was around to witness that giant boondoggle.

During the early 1960s, young Americans, by virtue of needing to reinvent or discover a wilderness of their own were forced to confront the question of where to find it now that there was almost no physical wilderness left. Initially there appeared to be several possibilities for locating that new wilderness.

While the exploration of the infinite wilderness of outer space appeared to be full of promise as a frontier experience for America, it was a viable option only for those few who possessed the necessary technological and financial resources to build, launch, and pilot spacecraft. As a result, the vast majority of people could only experience space travel and any resultant discoveries vicariously. They had no direct personal involvement in these adventures.

Initially, the jungles of South Vietnam seemed to some, at least, to hold the possibility of reaffirming the regenerative power of wilderness for Americans. America’s troops would be modern-day Natty Bumppos, Daniel Boones, and Davy Crocketts alive again in the forest and testing their wilderness skills and themselves in the defense of freedom against what now passed for Indians.

In seeking support for the war, President Lyndon Johnson even invoked a powerful and almost sacred symbol of the frontier during a December 1967 trip to Cam Ranh Bay when he told American soldiers to “nail that coonskin to the wall.”

In the end, however, the Vietnam war was to subvert the myth of the frontier and, in the process, turn American values and identity topsy-turvy. The war was to bring no sense of spiritual or physical renewal to America, just a sense of confusion and the finality of death.

Ultimately, many young Americans were to discover that the wilderness now existed within themselves and echoed that thought to each other. “All we had to explore was ourselves,” said Paul Kantner of Jefferson Airplane.

Do they still make Tang?