Editor's Note

This is the second post in a series that uses the study of nineteenth-century Dutch immigrant settlements in Iowa, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin to pose larger questions about how the international consciousness of rural communities in the nineteenth century challenge not only our understandings of the rural Midwest, but also of conceptions of American and European imperialism, settler colonialism, and worldwide missionary efforts.

This summer I am spending seven weeks in Holland, Michigan, on a generous research fellowship at the Van Raalte Institute. On the second day of my fellowship, I pulled out a remarkable scrapbook filled with hundreds of photos taken by a missionary to China in the 1890s. Most of these pictures were for the missionary’s personal use. One small booklet, though, accompanied a letter home to family and friends. The pictures attempted to capture daily life in China. This missionary wanted to provide his family and friends back in the United States with a glimpse into his everyday life in China.

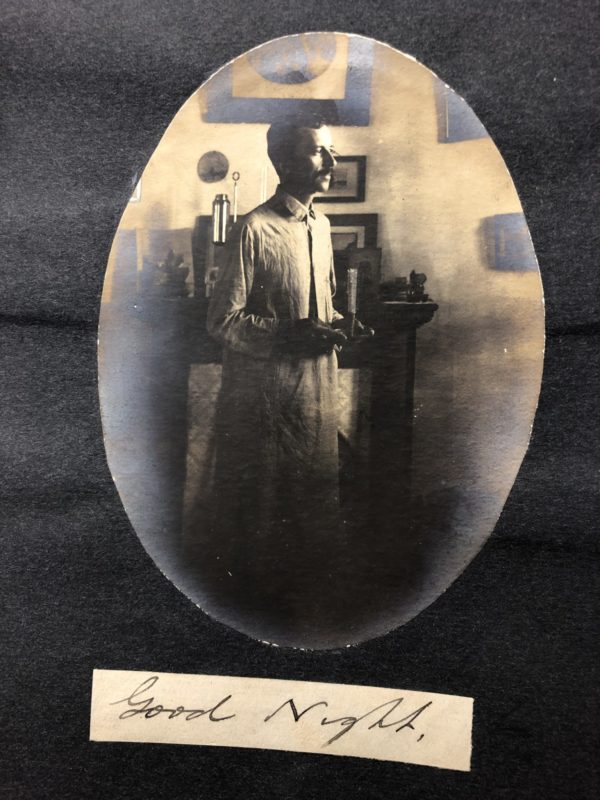

One of John Otte’s photos that attempted to capture the rhythms of his daily life for family and friends back home in Michigan.

This photo book was a rare find among this missionary’s materials. More common were the hundreds of letters he and his wife wrote to family and friends or the thousands of articles about China that appeared in local and church publications. In one form or another, Dutch immigrants who lived in rural communities in Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Michigan during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries received frequent updates about the political and religious climate in China, viewed, of course, through the imperialistic and evangelistic aims of the informants who wrote back with news from afar. These letters, articles, and newsletters vividly described China and offer a glimpse at the information that men and women in rural hinterlands used to form ideas about a nation thousands of miles from their homes.

They considered China to be a sought after prize for imperial powers.

The first post in this series on the international consciousness of these rural Midwestern immigrant communities noted that these men and women clearly saw themselves as imperialists. Their discussion of China illustrates that they didn’t just want to build colonies in the United States, but they also supported imperial expansion abroad. They did not resist the extension of empires, even at the expense of local populations.

In the late nineteenth century, hundreds of articles in Midwest-based, Dutch-language newspapers discussed the posturing of the French, Japanese, and Russians with rapt attention, rarely mentioning the potential implications for actual Chinese people or the Chinese government. Instead, the primary questions they considered in the face of expanding imperialism focused on their own missionary and economic prospects under particular regimes.

In fact, during the final 25 years of the nineteenth century, De Volksvriend—a widely circulated Dutch newspaper based in rural Iowa—made over 1400 references to China. Railroads advertised access to distant markets, news reports gave updates on the imperial jockeying by Japanese and European powers, and missionaries reported on their efforts to redeem a people that they believed to be lost in spiritual darkness.

In 1901, missionary Frances Phelps Otte wrote from her home in Xiamen, China[1] to her family and friends in rural Michigan and summarized the consequences of the partitioning of China among the great powers: “If China must be divided up, then we favor the Japanese, in preference to the French. We have no hesitancy in saying that the Japanese would favor the progress of Christian work, while the French would bring in Roman Catholics and much besides, quite as undesirable. Also we cannot forget the history of French rule in Madagascar, so we await with considerable interest the development of recent events.”[2]

If the Chinese were to be ousted from power, she just hoped that the Japanese would take over rather than French Catholics. Otte conceived of China as a place that could be divvied up between competing powers if necessary. Her ultimate concern centered on her evangelistic efforts not the sovereignty of the Chinese. Family and friends who read her letter or the many others who read her articles in the Christian Intelligencer—the Dutch Calvinist weekly in the United States—were being told clearly by a trusted correspondent in China that the country was weak and ready to be colonized by outsiders, but so long as mission work continued uninterrupted, all would be well.

As an aside, her note also reveals that she had a conception of French imperial policy in Madagascar, a noteworthy observation for a woman raised in a small Dutch immigrant colony in rural Michigan. It also makes her positive view of Japan apparent (which will be discussed in the next installment of this series).

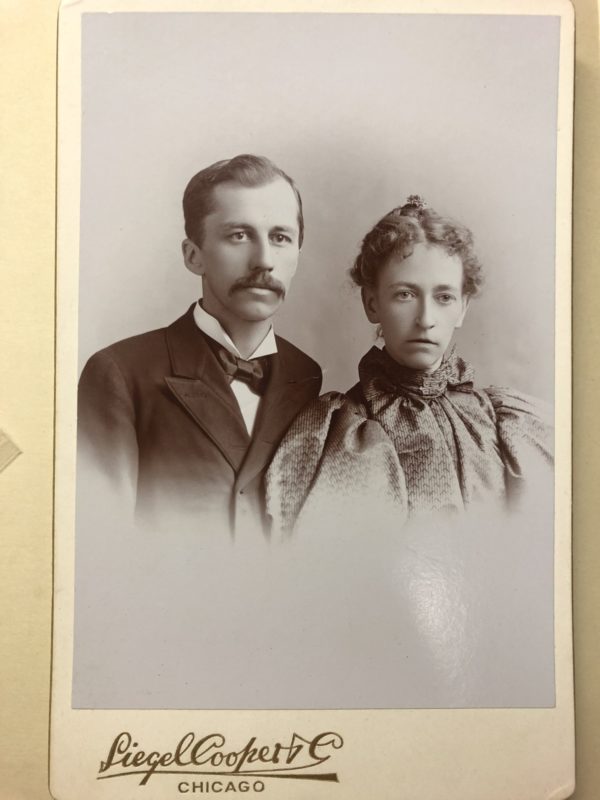

Photo of John and Frances Otte taken prior to their departure for China in the 1880s.

They viewed the Chinese as inferior to the West but thought they had potential.

In addition to seeing China as a pawn in broader global imperial and economic competitions, these rural communities also held opinions of China that reflected broader racist sentiments of the time.

Frances Otte’s husband John summarized his appraisal of the Chinese in an article circulated among Dutch communities in 1900. “There is but one thing necessary to make of China a grand nation,” he wrote, “and that is the religion of the Lord Jesus. But without this they are low brute savages, and as time goes on they will become lower and lower, as they have been doing for the last three centuries or more.”[3]

He viewed the Chinese as inferior and in desperate need of a religious conversation. His discussions of traditional Chinese medicine and inefficient local governance further justified his appraisal of the Chinese as inferior. In his estimation, though, the Chinese were not eternally lost. He believed the China held the potential to become a great nation if only it converted to Christianity.

The rural communities that received his missives encountered a vision of a nation with a need for vigorous Christian evangelization. By identifying the Chinese as an inferior people, he reiterated the racist understandings that characterized the age, but by not writing the Chinese off completely, he also added a sense of urgency to efforts to proselytize the nation. As eager rural churchgoers sent their money to the mission and young men and women dreamed of entering the Chinese mission field, they did so in response to a vision of the Chinese people as men and women in desperate need of Christian missionaries.

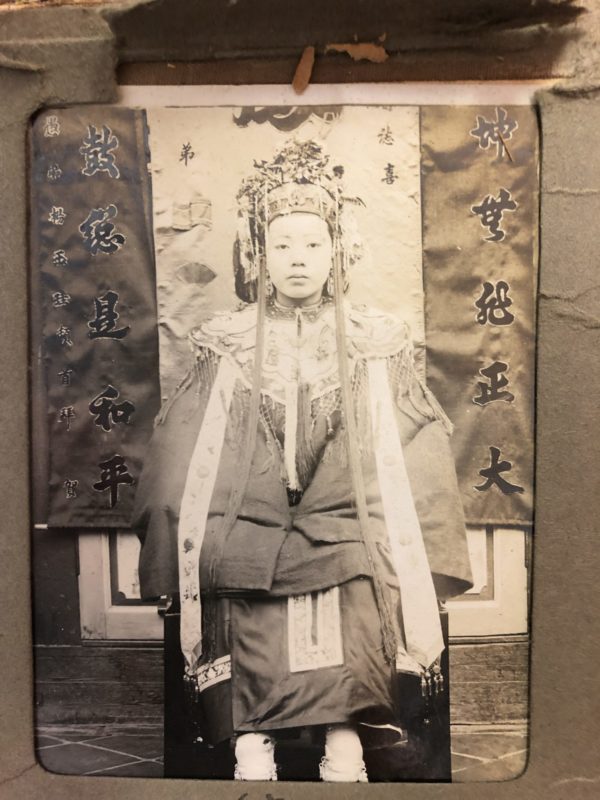

Photo of a Chinese bride taken by John A. Otte in the 1890s.

These rural communities saw China as a weak nation with a rich history but in desperate need of saving.

In 1939, a play appeared in these rural Midwestern communities that testified to the lasting impact of these updates from China in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the play’s opening act, set in the nineteenth century before the arrival of the Christian missionaries, a Chinese grandmother “hobbles on her bound feet” and desperately prays to idols for healing for her sick grandson.[4] She makes traditional Chinese medicines, calls doctors, and repeatedly prays at her family altar, but all for naught. At the scene’s end, the boy is dead. As the play progresses chronologically to the arrival of the Christian missionaries, its message becomes clear. In the playwright’s view, only Christianity and Western civilization, not Chinese religious, cultural, and medicinal traditions, could lead to healing and salvation. The play reflected the views held by these communities. It envisioned China in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a nation poised for colonization and Chinese people’s religious, cultural, and medical traditions as inferior to its own. Nearly four decades after the Ottes wrote home, the vision of nineteenth-century China that they helped to form still lingered.

Far from uninformed about China and the Chinese, these rural Midwestern communities teemed with information about China, which allows us to witness their well-developed international consciousness and more precisely to understand how they specifically conceived of China. All of this information about China, though, came from men and women with imperialistic or evangelistic aims and not from native Chinese men and women with deeper understandings of the social, political, and religious systems that shaped Chinese life. Ultimately, these rural communities did not see China as a mysterious foreign land or possess a nuanced understanding of the nation’s rich heritage. Rather, informed by their own imperial sympathies and evangelistic ambitions, they saw China as a nation ripe for expansion and the Chinese as a people in dire need of Christianity.

[1]Xiamen, China was referred to as Amoy, China in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

[2]Frances Otte, “Letter from China,” October 1901, H88-0117, John A. Otte Collection, Box 1, Joint Archives of Holland (JAH).

[3]John A. Otte, “The Conditions in China,” August 28, 1900. H88-0117, John A. Otte Collection, Box 1, JAH.

[4]”Progress of Nursing in China: With God Nothing Shall Be Impossible.” Performed May 1939. W89-1012 Jeannette Veldman Collection, JAH.

0