Editor's Note

This is the third post in a series that uses the study of nineteenth-century Dutch immigrant settlements in Iowa, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin to pose larger questions about how the international consciousness of rural communities in the nineteenth century challenge not only our understandings of the rural Midwest, but also of conceptions of American and European imperialism, settler colonialism, and worldwide missionary efforts.

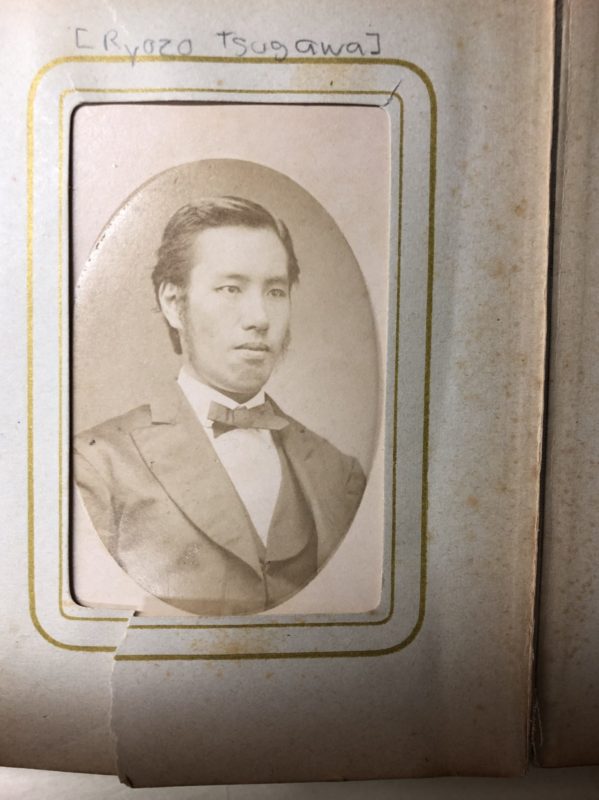

Ryozo Tsugawa’s arrival in rural Western Michigan in the late 1860s caused a bit of a stir, and the story of how he got there became something of a legend in its own time. A chance meeting between Tsugawa and Philip Phelps, the entrepreneurial president of Hope College, kicked off a series of dramatic of events. With gusto, Phelps first convinced the young student to make the journey inland to attend Hope, at the time an upstart college in the young Dutch immigrant settlement of Holland, Michigan. Then, faced with resistance from Japanese authorities, Phelps trekked to Washington D.C. to plead Tsugawa’s case directly to the Japanese consulate. Once permission was secured, he then cobbled together the necessary support to fund the young man’s time at the school. With special dispensation from the Japanese officials in D.C. and finances in place, Tsugawa enrolled.

“In the early seventies, a new life suddenly opened up before us, and strange ideas came into our minds when a foreigner from Japan, found in New York, by my father, came to live with us.” remarked Frances Otte, Phelps’ daughter and a woman who would go on to become a missionary to China. “How well I remember my father and mother discussing affairs a la Japan with this native. By the hour, they went over and over the accounts he gave them.”[1]

Tsugawa clearly made an impression in this small, Dutch immigrant community and though he was the first Japanese student to attend Hope, many more followed. At one point in the subsequent decades, 14 Japanese students were enrolled at Hope—a large number at college that, at the time, often graduated classes of fewer than ten students. For this small community, Japan was not just a foreign nation that they learned about in dispatches from missionaries or in books and newspapers. Japan, it turned out, existed right there in Holland, in the Japanese dormitory Zwemer House and in the frequent writings and talks offered by these Japanese students.

Japan was a hospitable, historic, and respectable nation.

The small community of Holland enjoyed an abundance of information about Japan, and importantly, they received it from several Japanese citizens who attended the community’s preparatory academy and college. Japanese students shared stories of the beauty, history, politics, class structures, social norms, entertainment pursuits, and agricultural models of their homeland.[2] The spoke of their mothers, siblings, and extended families, the pain of leaving home, and their desire to return there one day. Remarkably, they not only shared these stories, but they also wrote them down—much to the delight of historians. Westerners living or traveling abroad did not solely provide the information this community received about Japan. Japanese citizens themselves often acted as the sources for information about their homeland.

The picture of Japan that these students offered differed starkly from the community’s perception of other foreign lands. As we saw in a previous post about China, missionaries quickly cast China as a nation in decline with a people who were lost to superstition and poverty. Not so with Japan. The nation received praise for being a beautiful country and having a storied history full of figures who were honorable and brave.

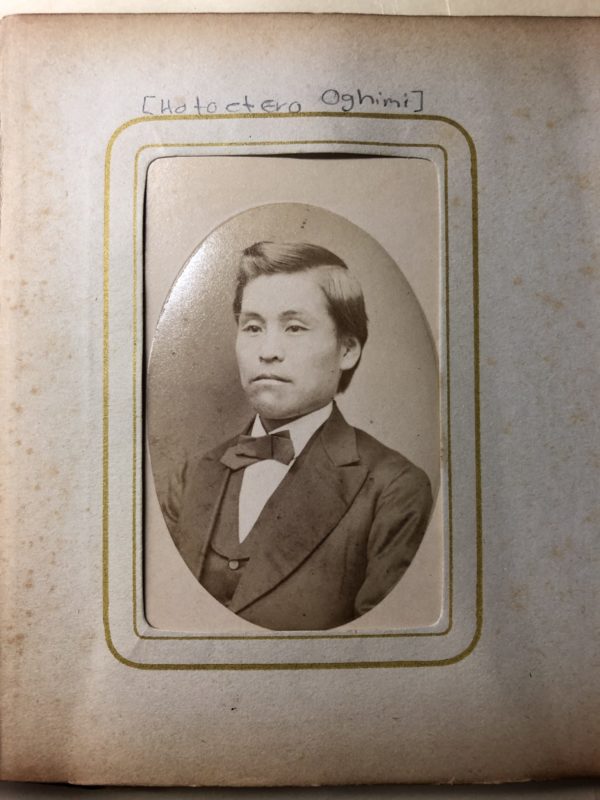

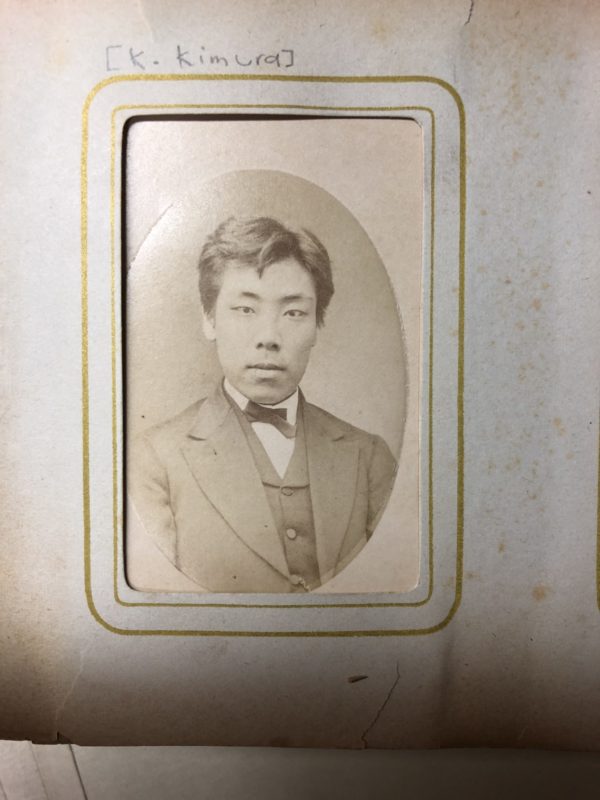

Men like Tsugawa or his classmates Kimaji Kimura and Motoichiro Ohgimi (often misspelled Oghimi by Westerners) certainly shaped this consciousness of their homeland, yet missionaries, too, wrote back with similar observations.

Unlike China, for instance, a missionary in the 1870s noted,“Japan and the Japanese have been very welcoming and polite, but never forthcoming or overly friendly. No persecution but very little enthusiasm.”[3]The missionaries lamented the apparent lack of zeal for Christianity, yet they also appreciated that the Japanese treated them kindly even if they ultimately proved imperious to evangelization. They echoed the perspective of the Japanese students. Japan was, in these missionaries’ minds, hospitable, historic, and respectable.

Japan was progressing.

In the 1870s, Japan’s embrace of industrialization formed a central narrative that circulated in this small town and throughout many other parts of the world. The vision of Japan was not just one of a static or declining country but of a nation on the rise.

Ohgimi states this clearly in a note set in Tokyo, Japan in 1874:

“It was truly wonderful that Japan, which was fifteen years ago considered as of the savage country of the Pacific Islands, is now becoming the most progressing land in Asia, adopting the ways of western civilization, casting down their bigotries of the old religion, and thus putting to shame the Empire of China, much older and larger than herself. The progress of civilization is most remarkable.”[4]

In no uncertain terms, he presented Japan as a nation on the move and the leading nation in Asia. Ohgimi and in other writings, Kimura made arguments for an ascendant Japan, especially in contrast to China.[5]

Many missionaries also adopted the idea of an advancing Japan, though they strongly qualified it in a way that men like Ohgimi and Kimura did not.

A near contemporary of Ohgimi and Kimura at Hope College, Albertus Pieters, later offered his own observations about Japanese progress after spending several years working in Nagasaki as a missionary. “The people of Japan are not yet ready for popular and constitutional government,” he remarked in a newsletter sent to supporters back in Michigan. “It makes one feel as if he has gone back two or three hundred years to live here in the East and watch the developments in Japan, China, and Korea… Here in Japan we have the last stages before full popular government, in Korea we have medieaval darkness.”[6]

Japanese progress may have placed the nation ahead of other Asian nations; however, in the mind of Pieters, and others back in these rural communities, Japan remained centuries behind Europe and the United States. Pieters’ voice is an important caution when attempting to reconstruct the international consciousness of this community, especially when men and women speak so positively about Japan and its trajectory. Men like Kimura, Ohgimi, and Pieters agreed that Japan was making significant progress, but they clearly disagreed about what that progress meant.

Japan was on the verge of conversion.

Religion, as always with this rural community, forms a central theme in its understanding of and engagement with international consciousness. Their primary goal, repeated over and over again, was the conversion of Japan to Christianity.

Correspondence from missionaries in the 1870s made it apparent that Japan remained outside of the Christian world. Two missionary sisters wrote back in the monthly missionary newsletter and bemoaned: “Notwithstanding the beauty and brightness of the Flowery Land, its inhabitants are yet in the darkness and blindness of terrible ignorance.”[7]

Despite its many laudable qualities, in the minds of residents of Holland, Michigan, Japan still needed to be converted to Christianity. Though, in the view of the men and women living in this community, Japan’s laudable culture and recent development suggested that it was on the verge of a massive wave of conversion.

Japanese students at the local academy and college reinforced this narrative. Kimura proclaimed: “I do not say that the European civilized nations are only changing our people’s manner, but its beneficial effects are to turn their minds to the true and glorious ‘way.’ Happy will Japan be, when Christ shall enable her children to bear his crops and follow him.”[8]More succinctly, Ohgimi simply characterized Christianity as “the true cause of civilization.”[9]Because they believed Christianity and civilization went hand in hand, for a rapidly industrializing nation like Japan, it was really just a matter of time before revival swept the nation.

Finding a through line of international consciousness

The emphasis on the conversion of the Japanese is not unique. This appeal to conversion occurred with the Chinese and will appear again throughout this series as men and women in this community think about engagement with people living in India, South Africa, and among Native American tribes. It is, I would argue, the through line of much of the international consciousness of this community.

Its consistency, though, proves illuminating. These folks have nuanced (though deeply flawed) visions of international communities. They distinguish between China, Korea, and Japan and characterize the people and cultures of these countries in markedly different ways. They know people who are from these nations or have lived for years in these places. Nevertheless, as we have seen in this series and as we will continue to see, even with diverse understandings different international contexts, they continue to return to a perceived need for Christianity as a defining feature of their international vision in nearly every case.

[1]Frances Phelps Otte, “Hope’s First Japanese Students,” H88-0116. Otte, Frances Phelps (1860-1956). Papers, 1882-1957. Box 1, Joint Archives of Holland.

[2]These are particularly apparent in Ohgimi and Kimura’s contributions to Hope College’s student journal Excelioraduring the years 1874-75.

[3]Missionary memoir in H.V.S. Peeke, Sketch of the Japan Mission (New York: Board of Foreign Missions of the Reformed Church in America, 1922), 5.

[4]Mito Ohgimi, “Foreign Correspondence, Yedo,” Excelsiora 4, No. 11 (April 1874), Excelsiora Collection, JAH.

[5]Kumaji Kimura, “The Chinese Student,” Excelsiora

4, No. 6 (February 1874), Excelsiora Collection, JAH.

[6]Albertus Pieters, “Quarterly Newsletter,” July 10, 1894. W88-060, John H. Karsten Papers, Box 1.

[7]Elizabeth and Mary Farrington, “Nagasaki,” Missionary Monthly Vol. 1. No. 12, (March 15, 1879), 95.

[8]Kumaji Kimura, “Social Manners in Japan,” Excelsiora 4, No. 4 (December 1873), Excelsiora Collection, JAH.

[9]Motoichiro Ohgimi, “Races of Men,” Excelsiora 5, No. 9 (March 1875), Excelsiora Collection, JAH.

0