In 1968, the English department at Stanford University employed thirty-eight tenure-track professors, one visiting professor, and five lecturers. Folding in the two emeritus professors listed in the university’s catalog for the 1968-1969 school year, that makes fifty-six forty-six faculty in the English department. Six of those fifty-six forty-six faculty members were women; only three of those women were on the tenure track, all at the level of assistant professor. So, women made up about seven per cent of all tenure-line faculty.

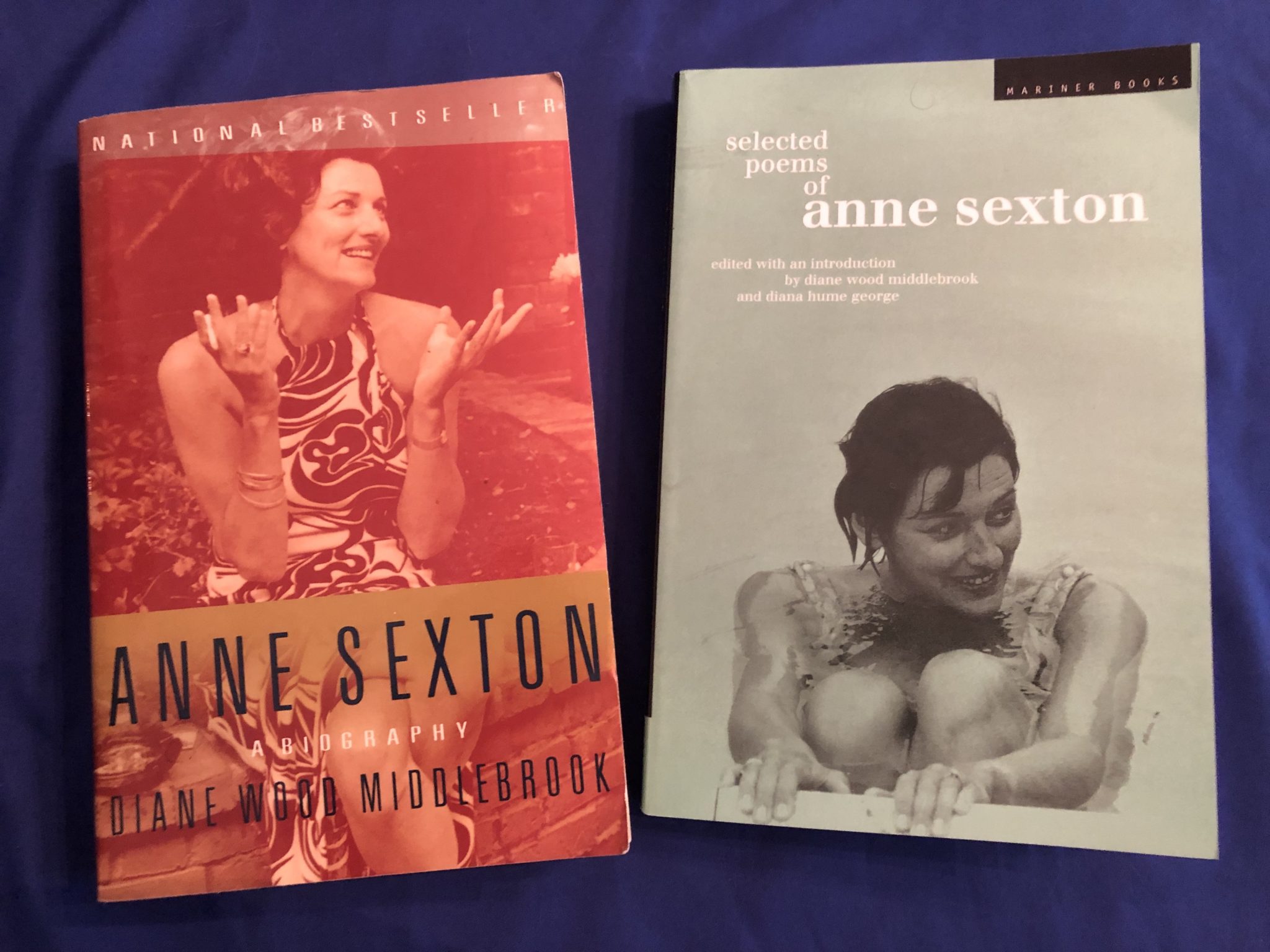

Diane Middlebrook was one of those three women. Though she wrote a joint biography of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, Middlebrook is best known for her biography of Anne Sexton. Her book, Anne Sexton: A Biography published in 1991, generated considerable controversy because she had been allowed to make use of hundreds of hours of audio recordings of Sexton’s therapy sessions with Dr. Martin T. Orne.

Middlebrook was working on this biography of Sexton in the late 1980s, during the final years of debate over Stanford’s Western Culture program, a debate in which she participated. I was an undergraduate at Stanford during those years, and I could have taken a class with Middlebrook. But I did not, because I knew that Middlebrook was a feminist scholar who focused on women’s writing, something I considered to be a niche interest and not worth my time.

Live and learn.

In skipping Diane Middlebrook, I also skipped Anne Sexton. To be sure, two of Sexton’s poems were included in Hayden Carruth’s anthology The Voice That Is Great Within Us: American Poetry of the Twentieth Century (1970). I obtained a copy of that anthology and read it cover to cover in junior high and high school, but Sexton’s two poems made no discernible impression on me. Instead, I was taken with Vachel Lindsay, Langston Hughes, Wallace Stevens, Richard Wilbur, James Wright, Robert Lowell, Theodore Roethke, Robert Bly, William Carlos Williams, and, above all, Robert Frost – grand old men of modern verse.

At Stanford in the 1980s (and now, I believe), English majors had distribution requirements within the major covering both period and genre. However, the same course could not meet two different distribution requirements within the major. I had taken both medieval English poetry (from Elizabeth Rowe) and 18th

At Stanford in the 1980s (and now, I believe), English majors had distribution requirements within the major covering both period and genre. However, the same course could not meet two different distribution requirements within the major. I had taken both medieval English poetry (from Elizabeth Rowe) and 18th

century poetry (from Frank Donoghue), but I used those courses to cover those respective periods. So I still needed a poetry class to cover that genre requirement. I ended up taking the poetry/poetics survey with Marjorie Perloff.

The major textbook for Perloff’s course was The Norton Anthology of Poetry

, 3rdedition. Nothing by Anne Sexton was included in that anthology, though it does include ten poems by Sylvia Plath. Perhaps the all-male editorial crew had concluded that one suicidal housewife-cum-poetess was enough. The anthology did include James Wright’s “A Blessing,” where Anne Sexton is present as Wright’s unnamed friend, his paramour. Indeed, per Middlebrook, “Blessing” was Wright’s nickname for Sexton during the epoch of their affair.

But some time between the third and fourth editions of The Norton Anthology of Poetry

, Anne Sexton became canonical, for Sexton is included in the fourth edition. I suspect Middlebrook’s biography of the poet had something to do with that change, as did the more general growth of feminist criticism within academe. More particularly, in 1988, the climactic year of the “canon wars” at Stanford, Selected Poems of Anne Sexton appeared in print, co-edited by Middlebrook and Diana H. George.

In the introduction to this anthology, the co-editors ask,

How will Anne Sexton be read twenty years from now? A hundred? Does she have a permanent place in American literature? The assumption underlying this collection is that her work will endure and that the terms of its endurance will undergo significant revision and expansion.

The editors then go on to discuss a number of features of Sexton’s poetry that they believed contributed to its enduring value: its early articulation of (white) feminist concerns with the constraints of the mid-century cult of domesticity; its metaphorical richness; its deeply personal subject matter, including a focus on “mental illness” and suicide; its larger concern with themes of death at the heart of a purportedly life-loving culture; its confessional tone; and its skeptical but searching engagement with religion.

For the editors of that 1988 volume, these were some of the distinguishing features of Sexton’s poetry which, taken together, distinguished her as deserving of a permanent place in the annals of American literature. And the editors expected that Sexton’s reputation as a poet could only grow.

Growth comes in unexpected ways. Some time between 1988 and 1991, Diane Middlebrook learned some things about Sexton, some facts about the features of her poetry and her life and the connection between them, that cast new light – or new shadows – upon Sexton’s work. Perhaps most significantly, Linda Gray Sexton, the poet’s oldest daughter and her literary executor, made the decision to disclose the sexual and emotional abuse she had suffered at the hands of her mother. Linda Gray Sexton wrote about the decision, and about the scathing criticism she endured for it, in the New York Times book review section. You can read that piece here: “A Daughter’s Story: I Knew Her Best.”

Linda Gray Sexton’s testimony in her own words (she wrote extensively about her relationship with her mother elsewhere) and as filtered through Diane Middlebrook’s biography surely changed the way many readers already familiar with the work of Anne Sexton viewed her poetry. That testimony is now part of Sexton’s permanent reputation in American letters. That very testimony may in fact imperil Sexton’s permanence as an author assigned in poetry and literature surveys. This is one of the fraught issues brought front and center by the #MeToo movement: when we learn that artists have also been abusers, do we keep reading their work? Do we separate the life from the work?

I don’t have a pat answer to this question. But I do think the question itself is vitally important now. Indeed, it is one of the crucial questions shaping current discussions of canonicity – even if those discussions do not invoke that term. If we accept (as I do) Guillory’s observation that “the canon” is an abstraction (rather than an hypostasis) that gestures toward whatever is currently on the collective syllabi of college classrooms at the moment. The canon does not shape the reading list; the reading list creates the canon.

So, given what we know of the life as well as the work, will Anne Sexton be on the reading list a hundred years from now?

In 1988, at the height of the Stanford canon wars, Diane Middlebrook thought so. By that time, she was a full professor. The entire English faculty (emeriti, tenure-line, and lecturers) comprised 78 persons, with fifty of those tenured or on the tenure track. Middlebrook was one of 12 women out of that group of fifty tenure-line professors.

That’s right – by 1988, the percentage of tenured/tenure-track women in the English department had doubled, from a measly 7-ish percent to a slightly-less-measly 15 percent.

In the 1980s, at least, Anne Sexton and Diane Middlebrook were both easily avoided.

So I am reading them now.

9 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I have corrected an arithmetic error in my first paragraph above.

God I hate math.

Also “Middlebrook was one of 12 women out of that group of fifty tenure-line professors” would equal 24%.

I f*cking hate math.

…when we learn that artists have also been abusers, do we keep reading their work? Do we separate the life from the work?

If someone thought Anne Sexton’s poetry worth reading before knowing about her abuse of her daughter, I don’t really see why that judgment should change afterward. Once published, the words of poems don’t change unless the poet herself or himself decides to publish a revised version or versions (which happens, but probably not all that frequently). And since the poems in question presumably haven’t changed, I don’t see that new knowledge about the poet’s life should drastically change one’s judgment of the work. I suppose, without knowing Sexton’s poetry, that there might be lines that appear in a different light or take on a different resonance, but that’s a different matter than deciding not to read someone on discovering new knowledge about their personal histories. There are always unusual or extreme cases and exceptions, but this is my general view.

Probably a good many poets, novelists, and artists of other kinds were (and perhaps are) not esp. admirable people for one reason or another. Some had or have political views one might not like, others perhaps were or are not very good people in their personal lives. If one’s going to start basing one’s judgments of literary merit to a significant (or exclusive) degree on these kinds of considerations, I think a fair amount of good and/or interesting work is going to be tossed out for reasons that are, in general, not adequate or good reasons.

p.s. I would take a roughly similar position on the issue of citing scholarly work and deciding what and whom to cite, but we’ve discussed that particular question before on this blog. The question of literary merit or canonicity etc. actually seems to me to present a more clear-cut case for separating work and life, when it comes to evaluation, than the citation question does.

Louis, bless you — I was composing my self-excoriating diatribe below when your comment here went up, and did exactly what I thought my own salient errors had made practically impossible: engaged with the larger problems posed in the post.

Here’s how Diane Middlebrook handled the issue, in a nutshell: “It is always disappointing to find that a work of art is wiser than its maker, but Anne Sexton’s play was both wiser and more compassionate than Anne Sexton the person.” (222) This comes in a chapter where she discusses early drafts of the play that would become Mercy Street, a play that recreates a primal scene of trauma, while Anne Sexton in real life was acting out that scene after a fashion with her own daughter.

Sexton (along with other “confessional” poets) was making the personal poetical in the same years, and along some of the same lines, that feminists were insisting that the personal is political. Thus she was browbeaten early in her career by one of her mentors, John Holmes, who, while formally supportive of her development as a poet, accused her of being performative and manipulative, accused her of making her poetry about her own experience, rather than about something universal — as if Frost’s or Lowell’s poetry was any less about their own experience. Self-referentiality is taken for granted in male geniuses; in women, it is unforgivable. How dare she be so large upon the page.

In any case, because I never read Sexton attentively before the revelations about the more disturbing connections between her work and her life came to light, it is difficult to read her “confessional” style without keeping in mind the trauma she endured and the trauma she inflicted. I suppose that is a feminist style of reading — something that would come as a huge surprise to 17-to-21-year-old me.

The personal is political; the personal is aesthetic; the aesthetic is political.

It has been almost 30 years since Middlebrook’s biography came out, and many many people still read Anne Sexton’s poems right alongside her life. Will #MeToo change that? Too early to say. Should #MeToo change that? I honestly don’t know.

Thanks, L.D.

It’s late in the evening here and I’m tired, so I’ll defer further comment right now except to say that in the case of a “confessional” poet — like Sexton, as I gather, or probably Lowell’s late work, or fill-in-the-blank — these issues might well be posed more acutely. Not sure.

And honestly — just to soliloquize here for a moment — the math is, like, the least significant part of this blog post. I’m hacked off at myself that it has become the most salient feature — though perhaps it’s easier to zero in on the details than to try to grapple with the larger problems. Anyway, I should have known better than to use numbers to illustrate anything; they’re utterly superfluous, a waste of pixels, and a complete derailing of the first blog post I’ve written in about two months. So that’s just fabulous.

Thank you for this L.D. I am a fan of “suicidal housewives-cum-poetesses?” and I honestly did not known about the allegations against Sexton until a few years ago. I did stop reading her work (though there are other abusive figures I have not severed ties to yet), but what i think about more is the ways in which it has already shaped my thinking. In her new collection of essays, Emily Nussbaum has an essay dealing with this regarding her teenage obsession with Woody Allen and the ways in which it shaped her life, interests etc. I think it’s hard for a lot of people. but I do think the art and the artist are one and the same and we should treat them as such. There are so many brilliant, amazing, creative writers and artists who do not abuse their power.

Holly, on reading Anne Sexton (now that I’ve done that), I guess my sense would be that it’s still worth doing, though it’s not just discomfiting, but searing, terrible at times, and the more you know about her life the more terrible it can feel. That too is an important effect or legacy of poetry, but a little of that goes a long way. There are some lyrics I want to look at again, but her phrases aren’t going to settle into my memory the way they would if I loved them. All that space is taken up anyhow with Spoon River Anthology and “The Chambered Nautilus” and Lord knows what else.

I think to have read Sexton and loved her and only later learned of the darkest things would be a very different and difficult experience. And I’m not sure that I would have been drawn to Sexton’s work in any case. But knowing what I knew about her life before I went through the collected poems, I couldn’t very well love her writing, though I was still able to be awed by it.

However, I am unwaveringly glad that I read Diane Middlebrook’s biography of Sexton. That was an outstanding book. I would recommend it to anyone.

I would also recommend this latest essay by Jill Lepore to anyone. My heart.

The Lingering of Loss