On occasion, I have used the country song “Automatic,” by Miranda Lambert, to introduce my students to the labor theory of value. In part, that’s because a lot of my students like country music (as do I, to be honest), but it’s also because the song’s understanding of the connections between time, effort, and value is usefully incoherent. Here’s the video. The key line in the song arrives in the chorus (full lyrics here):

Hey, whatever happened to waitin your turn

Doing it all by hand

Cause when everything is handed to you

It’s only worth as much as the time put in

It all just seemed so good the way we had it

Back before everything became automatic

In all likelihood, Lambert is not thinking of Marx’s concept of socially necessary labor time, which in the Marxist labor theory of value is the determining factor in how much people will value some thing in relation to other things. But Lambert’s theory of value is, in its own way, just as complex. “Automatic’s” verses feature a series of scenes of the analog good old days: manual transmissions, pay phones, Rand McNally atlases, “[car] windows with the cranks,” cassette tapes. No matter that these technologies only seem primitive in comparison with today’s alternatives—that on their own, they actually require considerable engineering. What is important to Lambert is that they require effort: it is harder to roll down a window with a crank than with a button.

But “the time put in” has a second meaning as well: it is also about delayed gratification. Waiting is itself a kind of effort, a form of labor. Or at least it appears to have been effortful in retrospect: in reality, we simply took the expanses of time necessitated by processes like developing film or communicating by letter for granted. But that form of waiting was a form of discipline—consumer discipline, in the same sense that clocking in on time for work is labor discipline. Both disciplines transform duration into value: things become worth more or less depending on “the time put in.”

Like Alanis Morissette’s “Ironic,” “Automatic” isn’t consistent (or accurate) in its examples: Lambert adduces Polaroid photos (“the kind you gotta shake”) in her catalog of virtuously non-instantaneous items from the past. I’m old enough (and she is too) to know that everyone at the time considered that photographic technology shockingly immediate in its delivery: Polaroid was automatic if anything was. Explaining the incoherence of the song’s ideas about what is and what is not automatic, however, is a good way to get my students talking about what they think requires effort and how they value that effort—which was the point to begin with.

***

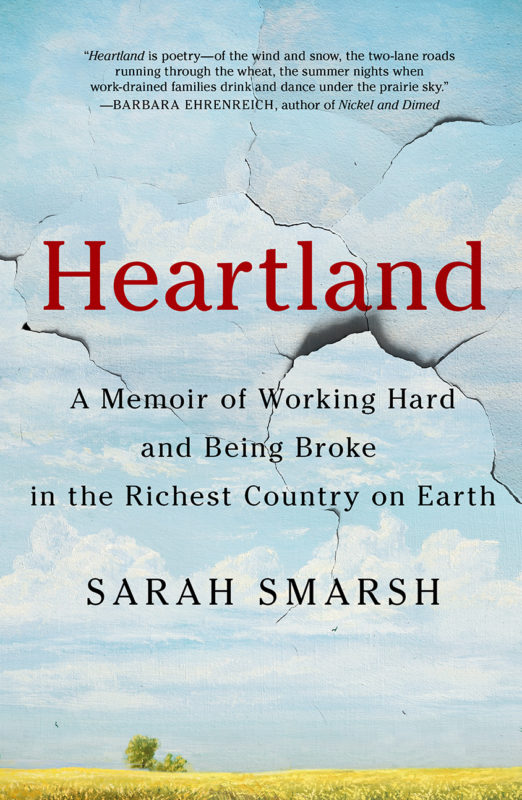

Courtesy of SF Chronicle

Sarah Smarsh’s ideas about labor and value are considerably more sophisticated than Miranda Lambert’s, but I don’t think she’d be offended if I said they come from not dissimilar worlds. Smarsh is the author of Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth, a book that came out last year and that I cannot recommend highly enough. Heartland is everything people should have been listening to when they were paying attention to J.D. Vance and his Hillbilly Elegy; I would even compare it favorably to Tara Westover’s Educated, which (unlike Vance) I do think fairly highly of.

What Smarsh’s book has that those books lack is a kind of certainty and steadiness of purpose. Although it is labeled a memoir, Heartland

is more like a work of vernacular political economy. The latter part of the book’s subtitle, “Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth,” is itself a political economic argument, calling to mind the title of Henry George’s enormously influential 1879 book Progress and Poverty. Both isolate the paradox of continuing (and, in fact, deepening) poverty coinciding with extraordinarily rapid accumulations of wealth as the most fundamental social problem to be explained. Inequality in and of itself is not unusual, historically speaking, but this—say George and Smarsh—this bifurcated economic order is unnatural, as if two wholly different countries were overlaid on one another but none of the wealth created in one country spilled over into the other.[1]

Or here is how she puts it:

Wealth and income inequality were nothing rare in global history. What was peculiar about the class system in the United States, though, is that for centuries we denied it existed. At every rung of the economic ladder, Americans believed that hard work and a little know-how were all a person needed to get ahead…

But the American Dream has a price tag on it. The cost changes depending on where you’re born and to whom, with what color skin and with how much money [is] in your parents’ bank account. The poorer you are, the higher the price. You can pay an entire life in labor, it turns out, and have nothing to show for it. Less than nothing, even: debt, injury, abject need. (Smarsh 2018, 42)

It is this laser-like focus, this basic question—how is it possible that you can work unceasingly and still not be able to afford basic necessities?—that drives the book forward. And it is not a rhetorical question. Smarsh asserts forcefully that there is something absurd about a society that will value a person’s hard work as somewhere below the cost of keeping them healthy and basically comfortable.

The person who drives a garbage truck may himself be viewed as trash. The worse danger is not the job itself but the devaluing of those who do it.[2] A society that considers your body dispensable will inflict a violence upon you. Working in a field is one thing; being misled by a corporation about the safety of a carcinogenic pesticide is another. Hammering on a roof is one thing; not being able to afford a doctor when you fall off it is another. Waiting tables is one thing; working for an employer whose sexual harassment you can’t afford to fight and risk a night’s worth of tips is another. (Smarsh 2018, 45)

Smarsh is emphatic in stressing the dignity of manual labor; at times there is even a religious tinge to her descriptions of farming and construction work. But she is equally emphatic in stressing the contingency that underlies the division of labor. “There’s an idea that laborers end up in their role because it’s all they’re suited for. What put us there, though, was birth, family history—not lack of talent for something else” (Smarsh 2018, 44).

That sense of contingency—the notion that most of the factors guiding you toward your occupational future are radically separate from issues of innate talent or even suitability—determines much of what Smarsh finds valuable about work. The contingency of the division of labor—we all might have been better at something else, and someone, even many people might have been better at our job than we are—is a great leveling force, a blow struck for humility and a mandate for reexamining the way we set different values on different kinds of work.[3]

Rather than supposing—as we often do—that the kinds of jobs that rich children want are at once the most challenging, the most universally desirable, and the most socially enriching, it is possible that those jobs are valued highly in the first place because rich parents do them.

It is possible, in other words, that different forms of labor are valued differently not because of some kind of formal calculation ranking occupations by the good they contribute, or by their intrinsic difficulty, or by the level of demand from people wanting to fill that occupation. Rather, we tend to value those professions we think rich people are likely to value, and the best way to determine that is to look at which professions they actually choose for themselves.

But that process in itself suggests that, regardless of whether we think a commodity is objectively worth “the time put in” or not, the value placed on an occupation is entirely subjective. There is no application of the labor theory of value to explain why doctors are paid more than nurses, much less why they are paid more than farmers. Conventional arguments about the value coming from “the time put in” to additional years of schooling and training seem relatively peripheral considerations from Smarsh’s point of view.

What Smarsh comes to is something like a marginalist theory of labor itself—the exchange value of labor (what someone gets in wages or salary) should be connected in some way to the value that the laborer themself places upon it. Their pride in their work, their enjoyment of their labor, ought to count for something.

Notes

[1] I’m thinking here of China Miéville’s 2009 novel The City and the City, which imagines an arrangement like this.

[2] In fact, garbage collection is one of the five most dangerous jobs in the United States, well above police officer or firefighter.

[3] I should note here that I’m extrapolating somewhat from what Smarsh has written, though I think the rest of this paragraph and the next follow naturally from her arguments.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I think all forms of work contributing to the construction, maintenance, or reconstruction of the social order, in other words, to the general welfare and well-being, as well as possibilities for self-fulfillment and eudaimonia (by way of individuation and self-realization), should be understood as intrinsically valuable and absolutely necessary to a society, and thus any functional division of labor should assume this as an axiomatic premise. Incidentally, I think it’s rather silly to imagine, if not impossible that “the exchange value of labor (what someone gets in wages or salary) should be connected in some way to the value that the laborer … places upon it.” No social or economic division of labor should obscure the fundamental facts of human interdependence and unity (would can and should of course extend this principle into the ecological and environmental realm), including the intrinsic dignity of every human being. The myriad “powers, capacities, character and energies” that go into various kinds of labor are socially formed and derived (i.e., we own neither our labor nor the products of same, even if it be left to us, at least in part, to have some say in what we should do with our labor) and subjective determination of its or their worth or value is arbitrary if not incoherent, if only owing to reasons generated from what we know of human psychology. That one should value one’s labor, or find joy or fulfillment in their work, whatever particular form it takes, is, however, important and not, I would think, controversial. And every person should have a right to work, for it is often by means of work that “a man acquire[s] such basic human qualities as a sense of self-respect, dignity [this kind of dignity is distinguished from that cited above], self-discipline, self-confidence, initiative, and the capacity to organise his energies and structure his personality.” Forms of labor that are considered dangerous, physically demanding, or otherwise deemed undesirable yet socially necessary should be shared in some manner by all (be it during one’s youth, or as period time devoted to this particular contribution to the common good, what have you).

Let us recall, with the political philosopher (some would prefer ‘theorist’) Bhikhu Parekh (examining some ideas of Gandhi), that “the efforts of countless men and women flow[ ] into one another to produce even a simple object, rendering impossible to demarcate the distinctive contribution of each.” Moreover, we should not forget that these efforts “occur[ ] within the context of the established social order whose silent and unnoticed but vital contribution [should] not be ignored either.” There is, therefore, no logical basis on which any individual can claim a specific reward (e.g. wage or salary), regardless of whether or not it is tied to the value a worker might place on their individual contribution. Much as “moral and cultural capital” is, or should be, “available by its very nature to all [members of society] as freely as the air [we breathe], so too should material and economic capital circulate freely within the constraints of fundamental moral principles, for the “customs, values, traditions, ways of life and thought, habits, language,” and educational, social, political, and economic institutions that constitute a social order were and are “created by the quiet co-operation and the anonymous sacrifices of countless men and women over [at least] several generations, none of whom asked for or could ever receive rewards for all their efforts.” However we determine the “basic necessities of life,” their production should be collectively “owned” and managed to prevent their exploitation and to assure our very survival. The intertwined principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity (or community) should guide not only the political order but the social and economic order as well (political and economic interests are cut from the same cloth, hence ‘political economy’). And the economic order should thus be seen as generally subordinate to moral and “spiritual” (in the widest if not deepest sense that transcends religion) principles. And thus any economics that fails to satisfy basic human needs of all human beings, or is not individually and collectively sensitive to our human capabilities and “functionings,” is neither humane nor just.

What a great review, Andy. This book has been on my radar for a bit but it’s gone to the top of my list.

On the subject of themes of work in country music, are you familiar with Margo Price? She also has several songs that touch on these issues, including one called “Pay Gap” that includes an intriguing line about feminism which I can’t figure out how it is intended. I would definitely recommend it to continue following this scent you’re tracking here!