As a youngster, I had a thumbnail scheme for understanding genre in popular music. Rock was about wanting, funk about having, and country about losing what you had. Later, not long after I began to seriously explore the third category, I refined my label. Our little new wave band had been playing the circuit for several years when I started listening to Hank Williams‘ 40 Greatest Hits. We were in our late twenties, a transitional time, and we laughed at how pitiful the songs were. Laughed darkly, I should say. Some of these songs –a 1950 recording titled, “My Son Calls Another Man Daddy,” comes to mind–cut a little close to the bone.

I started thinking of country music as “music for adults.”

In her essay from The Honky Tonk on the Left: Progressive Thought in Country Music (University of Massachusetts Press 2018), Stephanie Vander Wel uses the phrase, “the complexities and paradoxes of adult love” to describe the topic of honky-tonk songs. Strictly speaking, country and western is a broader category than honky-tonk, a distinction blurred somewhat in the book’s title, though not in the essays inside. Honky-tonk is a subgenre forged in the working-class joints of the Southwest migration. Distilled from big-band Western Swing, it has sonic and historical affinities with electric blues, with rock and rock, and with the postwar modern jazz combo. Honky-tonk overlaps with what is sometimes called “classic country” but is harder-edged, less prettified than the better-selling Nashville sound.

In her essay from The Honky Tonk on the Left: Progressive Thought in Country Music (University of Massachusetts Press 2018), Stephanie Vander Wel uses the phrase, “the complexities and paradoxes of adult love” to describe the topic of honky-tonk songs. Strictly speaking, country and western is a broader category than honky-tonk, a distinction blurred somewhat in the book’s title, though not in the essays inside. Honky-tonk is a subgenre forged in the working-class joints of the Southwest migration. Distilled from big-band Western Swing, it has sonic and historical affinities with electric blues, with rock and rock, and with the postwar modern jazz combo. Honky-tonk overlaps with what is sometimes called “classic country” but is harder-edged, less prettified than the better-selling Nashville sound.

These are nit-pickable qualifications, of course, of concern to aficionados, academics, and nerds. Because I happen to fall into all three categories, I also appreciated Vander Wel’s more elaborate rendering:

emotional men crying over the ideals of some forgotten past and struggling with the anxieties of dislocation and alienation in industrialized urban centers.

1957 publicity photo of Webb Pierce as he appeared on the television program Ozark Jubilee. Public domain.

Emotional men crying. That’s the key idea in Vander Wel’s essay, “Weeping and Flamboyant Men: Webb Pierce and the Campy Theatrics of Country Music.” Pierce was a contemporary of Hank Williams. His best-known song, “There Stands the Glass,” was recorded in 1953, the year Williams died of heart failure at age twenty-nine. Vander Wel describes Pierce as a crooner. Again, some clarification is called for. Crooning, a word that came out of minstrelsy, was used to describe a particularly intimate and hyperemotional way of singing. The style rose to popularity in the 1920s with advances in the technology of recording and amplification.

Like much of the popular culture constructed in that decade, crooning recognized no borders of race, gender, or ethnic group. All kinds of people did it; all kinds of people loved it–at least for a while. In her book, Real Men Don’t Sing: Crooning in Popular Culture (Duke UP, 2015), Allison McCracken shows how this cultural messiness was put to order when in the following decade the political and commercial authorities established clearer lines. As part of this process, the effete tenor Rudy Vallee, for example, was replaced by Bing Crosby, whose warm baritone was shorn of the jazz age hysterics. Crosby came to represent the narrower possibilities of the white, male voice: lower-pitched, more emotionally contained.

During and especially after the war, honky-tonk crooners challenged those constrictions. This is where Vander Wel builds on McKracken’s thesis. Honky-tonk songs were tears-in-your-beer narratives of failure and self-abasement. Pierce and the new crooners who sung them pushed back against the now gendered and racialized standard, not only in sound but in presentation. They wore bright-colored suits, decorated with intricate Western themes. Long before glam rock or Prince, Webb Pierce “embellished the visual markers of masculinity” to “dazzling spectacle.” Pierce’s “androgynous glamour” had something of the twenties in it, something subversive and unpoliced.

During and especially after the war, honky-tonk crooners challenged those constrictions. This is where Vander Wel builds on McKracken’s thesis. Honky-tonk songs were tears-in-your-beer narratives of failure and self-abasement. Pierce and the new crooners who sung them pushed back against the now gendered and racialized standard, not only in sound but in presentation. They wore bright-colored suits, decorated with intricate Western themes. Long before glam rock or Prince, Webb Pierce “embellished the visual markers of masculinity” to “dazzling spectacle.” Pierce’s “androgynous glamour” had something of the twenties in it, something subversive and unpoliced.

Potential exceptions spring to mind; still, I see Vander Wel’s point. “There stands the glass. It’s my first one today.” This is not a Bing Crosby lyric, at least not the mature Crosby. Likewise, a Nudie suit seems somehow beneath Crosby’s dignity. I know what Vander Wel means, too, by this music’s subversive appeal. When I began systematically investigating the country and western of past decades, I found a lot to like, but it was the wrecked soul testimonials that gave the music its edge. “Long Black Veil.” “Darkness on the Face of the Earth.” And along with “There Stands the Glass,” the many tributes to self-medication: “Just One More.” “The Bottle Let Me Down.” I’m not even trying to hide it anymore, these songs say. I’ve let the reins go completely. This did challenge the officially sanctioned posture of command. Despite the literalness of the lyrics—in country, there was no obscurity in meaning, no modernist Dylanesque poetics–they contained much that couldn’t necessarily be explained or justified, only felt.

That was years ago, the early 1990s or thereabouts, and I was one of many thousands on a similar trajectory. We knew punk, new wave, ska, and reggae. We’d learned quite a lot about world music. Now it was time to dig into roots a little closer to home. That was harder than it sounds. There was a lot of schlock and corn to wade through. More troubling was the music’s association with reactionary politics and racism. Somehow, ways were found around these obstacles. It was as if a window had opened to find the subversive, progressive strains in country music that Vander Wel and her colleagues write about.

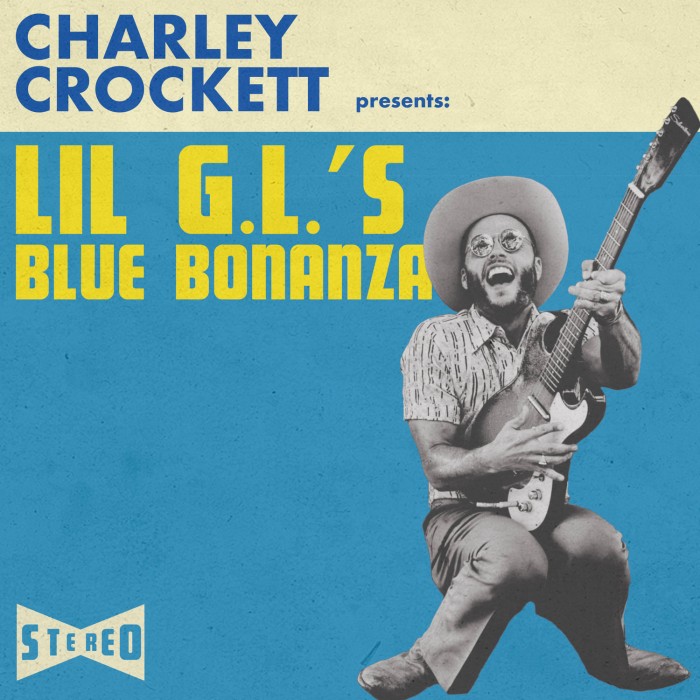

Reading Vander Wel brought back those early days of discovery. So did the new Charley Crockett record. Crockett is a rising star, a Texan, of distant relation to Davy, supposedly, with a great voice and a swinging honky-tonk band. His new album, Lil G.L.’s Blue Bonanza, is a collection of covers, many of them songs I’d first gotten to know way back when. Side one ends, for example, with “Burn Another Honky Tonk Down,” a song with all the dark qualities I mentioned. The singer works in a sawmill by day, producing the lumber used to build honky tonks, which he then goes out and burns down after hours—burns down not figuratively but literally.

I remember loving that song when I first heard the 1968 version by George Jones, the great crooner of honky-tonk’s golden age. It was on a mid-1980s Rounder Records compilation that anticipated the zeitgeist. Jones appears on the cover in a bright red western suit and a well-greased military brush cut. What a bizarre-looking figure! Inside was the most soulful white voice I’d ever heard.

Crockett’s version of “Burn Another Honky Tonk Down” is affecting, but after #MeToo, and in the present political climate, I’m unable to be as forgiving—or as clueless—as I once was about that song. Why has the singer become an arsonist targeting honky tonks? That’s where he knows he’ll find “her,” of course, the faithless wife out there spending his money, “having herself quite a ball.” Male crying in honky tonk may have posed alternatives to the normative racial and gender roles, but it was also used quite regularly to attack and stigmatize women for not adhering to the roles assigned them. It pains me now that I partook of this sort of projection, that this was a version of male crying in which I found some catharsis.

Times were different then. What I was fine with overlooking before now stands out like a beacon. For related reasons, I haven’t wanted to listen to country music, or even roots music, for quite some time. That’s why the Charley Crockett record came as such a pleasant, if qualified, surprise. I can appreciate Vander Wel’s argument about male crying as “a tool for social critique and political change.” Lately, however, during the Kavanaugh hearing for example, we’ve seen a kind of male hysterics deployed for the opposite purpose–to safeguard privilege, to resist change. Events and the cultural temperature shape reception. The window that was open back in the 1990s seems to be well-closed today.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Super interesting stuff. Lately Eran has compiled a playlist on Spotify we really like he dubbed “Southern Discomfort,” filled with progressively-edged bands and artists from the last two decades. So Drive By Truckers, Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit, Mandolin Orange, James McMurty etc. I’ve been struck by how effective this music is at hitting me right where it hurts; Isbell’s “White Man’s World” is one of the most haunting and heartfelt songs I’ve heard in a long time. (Speaking of the “Nashville sound,” there’s such a brilliant couplet of lines in that song connecting it to sexism.) I’ve noticed, with a dose of embarrassment about it, that since I’m used to this country sound I feel a kind of relief at hearing the ideas I care about articulated by a musical form that I don’t feel like an awkward foreigner to, as with hip-hop and soul. Like I’m not running as nearly much a risk of being a poser with my protest music. Anyway, a small thing, but with political culture small things can be so huge for many individuals.

I would like to hear that playlist. I’m going to guess that Steve Earle is on it. I like to see him just to hear his political rants between songs. Last time I saw him, though, maybe a year ago, he avoided ranting, was almost apologetic about it, promising at one point to weigh in on the current climate with a set of new songs … at a later date.

The day I posted this I listened to Chris Shiflett’s interview with Charlie Crockett on his podcast “Walking the Floor.” Without getting directly political, Crockett spoke eloquently about the two Texases, the ugly and the diverse, and the musical tradition of that diverse Texas. It was just what I needed to hear.

It’s hardly a new point, but there were lots of emotional, conflicted anti-war country songs during Vietnam. For all of Merle Haggard’s “If you don’t love it, leave it” schlock, there were songs like Waylon Jennings’s “Six White Horses.”

Anyway, thanks for the post!

Cam, thank you for the Jennings example, I don’t know that one. As for Haggard’s politics, the situation is mixed. Many argue that “Okie from Muskogee” was meant ironically. Others point to “Irma Jackson” and “They’re Tearing the Labor Camps Down” as examples of progressive sentiment.

Won’t claim to know v much about any of this, but is there a line of country (not honky tonk) songs that protest, gently or otherwise, against conditions of work etc? “Take this Job and Shove It” comes to mind and, in a gentler tone, “18 Wheels and a Dozen Roses.” The latter isn’t a protest song but one does get the feeling that the narrator will be glad when he doesn’t have to drive that big truck any more.

On a different note, how does honky tonk relate to bluegrass, if at all? There were crooners in all kinds of genres, probably, and bluegrass definitely had its share.

Bluegrass is another midcentury genre. It developed east of the Mississippi, as opposed to west with honky-tonk, and it isnt, as honky-tonk is, a dance music. Bluegrass was pretty much conceived by one genius, the band leader and mandolin player, Bill Monroe. Monroe certainly sang high–the high harmony of the high lonesome sound. He wasnt progressive in his attitudes. The cultural/political differences between a bluegrass festival and a string band festival are striking, in my experience. The string band tradition reaches back into the 19th century and was part of what fed into that 1920s stew.

Thanks. I’ve listened a bit to B. Monroe (via CD, which, along w radio and v occasionally YouTube, is the only way I listen to anything). It’s not something I put on very often though. I note yr pt about the string band tradition – interesting.