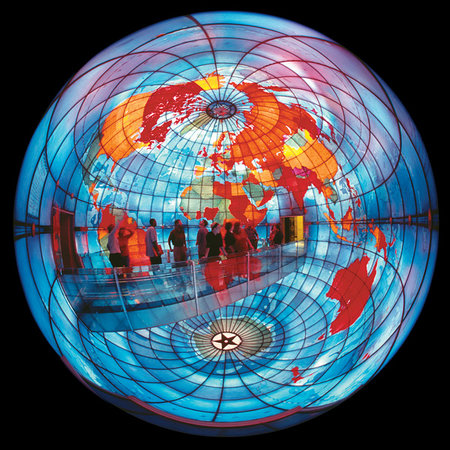

It may be the best-read map in Boston, and the least understood artifact of modern religion. In early 1933, with his prestigious commission for the new Christian Science Publishing Society headquarters nearly complete, Boston architect Chester Lindsay Churchill persuaded First Church directors to cap the building with a unique feature: a 30-foot-high, stained-glass globe of the world pictured from inside of it. On blueprints, he called it simply the “Mapparium,” meaning “a place for maps.”[i] According to Churchill, the Mapparium would help the Church to “extend its influence and establish a more friendly contact and understanding with people generally.”[ii] Following David Woodward’s tripartite classification scheme of the map as a social document, visitors can “read” the Mapparium on different levels: as a stained-glass image of globular projection; as a vehicle for the promotion of Christian Science; and as an artifact of early 20th-century political cartography.[iii]

It may be the best-read map in Boston, and the least understood artifact of modern religion. In early 1933, with his prestigious commission for the new Christian Science Publishing Society headquarters nearly complete, Boston architect Chester Lindsay Churchill persuaded First Church directors to cap the building with a unique feature: a 30-foot-high, stained-glass globe of the world pictured from inside of it. On blueprints, he called it simply the “Mapparium,” meaning “a place for maps.”[i] According to Churchill, the Mapparium would help the Church to “extend its influence and establish a more friendly contact and understanding with people generally.”[ii] Following David Woodward’s tripartite classification scheme of the map as a social document, visitors can “read” the Mapparium on different levels: as a stained-glass image of globular projection; as a vehicle for the promotion of Christian Science; and as an artifact of early 20th-century political cartography.[iii]

Just as a map is a rhetorical device that reveals historical power relations, the concave Mapparium embodies a distinctive worldview of 1935. Here at the blog, I’m spending my warm-weather posts highlighting some religious sites and their colorful layers of history. Manuscripts are key, but material culture is another must for scholars writing intellectual history. Let’s start this road trip by considering how Christian Scientists curated a usable past.

Debuting during the Great Depression, the Mapparium’s presence had an immediate impact. Record crowds marveled at the ability to walk inside a hollowed-out map. More than ten million visitors have crossed the Mapparium’s 30-foot glass bridge since then, admiring its geographical singularities and acoustical quirks. Sensitive to the artistry and science of the medieval mappamundi tradition, as well as the lingering Victorian fad for geography-as-spectacle, the architects placed it at the religion’s center, the Mother Church. For almost two years, a small army of contractors and artisans labored to design, fire, transport, and set 608 panels of glass that show the world eternally frozen at the instant when doors opened to the public, in June 1935. Relying mainly on cartoons made from the Rand McNally world atlas of 1934, and working with the New York City art glass firm of Rambusch & Company, Churchill inked world geography into a sprawling, architecturally diverse complex.

Modeled largely after the spinning globe that graced the New York lobby of the Daily News, as well as James Wyld’s Great Globe (London, 1851-1862), and other 19th-century panoramas

, Churchill’s plan for a “spherical map room” earned early support. Architectural critics, structural engineers, and national clergy were impressed by the sheer ambition of the finished project—if a little uncertain that the controversial religion would win over followers with such an extravagant display. “In this place, geography steps out of a book and becomes real and understandable,” one Congregationalist clergyman wrote, adding: “The Christian church also has its map-room and its Mapparium. We enter when we sing such hymns as ‘Jesus shall reign where’er the sun, Does his successive journeys run, His kingdom stretch from shore to shore.’ But in spite of all this, we are not on the whole a map-minded people.”[iv] The Mapparium’s popularity proved otherwise.

For the Mapparium’s prospective readers, maps were a readily available source of both scholarship and entertainment. American popular interest in maps continued into the 1930s, entrenching a cultural habit. Among American cartographers, an era of “great surveys” yielded a proliferation of novelty maps, pocket atlases, street-level views, and keen-eyed map-readers.[v] Systems of measurement improved, fueling the scientific explorations that mapmakers needed in order to execute reliable designs. Thanks to the adoption of the Representative Fraction, and new techniques like aerial photography, steel engraving, and advanced lithography, Rand McNally’s offset presses were able to run off 1,500 two-color maps an hour.

For the Mapparium’s prospective readers, maps were a readily available source of both scholarship and entertainment. American popular interest in maps continued into the 1930s, entrenching a cultural habit. Among American cartographers, an era of “great surveys” yielded a proliferation of novelty maps, pocket atlases, street-level views, and keen-eyed map-readers.[v] Systems of measurement improved, fueling the scientific explorations that mapmakers needed in order to execute reliable designs. Thanks to the adoption of the Representative Fraction, and new techniques like aerial photography, steel engraving, and advanced lithography, Rand McNally’s offset presses were able to run off 1,500 two-color maps an hour.

Just as Churchill submitted his order for the Mapparium’s first set of glass plates, new academic journals, university training programs in cartography, and professional societies all began to flourish.[vi] Americans were ready to welcome the Mapparium in the midst of their city, a colorful site that braided together education and faith. “Our work is being done in globular projection, and it is about the first time it has been tried,” Churchill reported. “You are going to have something which is absolutely correct.”[vii] The Mapparium was billed as a novel, family-friendly site that was fun, free (originally), and, in the summer of 1935, one of Boston’s few air-conditioned attractions.

Construction began in April 1934. For such a large-scale project, Churchill’s team of artisans moved with impressive speed and attention to detail. The cooperative making of the Mapparium was a labor-intensive process, with handpicked professionals ready to apply a single, special process to each pane of glass. First, Churchill took a regular 1934 Rand McNally world map and photostatically enlarged it, retaining the descriptive text and lettering of principal cities. Working from a grid, Rand McNally geographers then produced a set of full-size cartoons. Churchill was emphatic that a viewer’s greatest distance from any country in the Mapparium should not exceed 15 feet, except at the North and South poles, to ensure that “every one of the words will be legible from every point.”[viii] His greatest concern was that amid all the architectural excitement of making the Mapparium, the actual cartography might prove too faulty to present on the Church’s behalf. To counter this, he hired fact-checkers to review the cartoons against map collections in the Library of Congress and the U.S. Department of State. Only once he had verified the map data and alerted Rand McNally to any errors were the final cartoons sent to New York for the next stage of production.[ix] There, Rambusch family artists traced the cartoons onto ¼ to ½-inch thick glass plates, and applied a powdered glass-paint mixture before firing the panels in kilns with asbestos cradles.

The Church’s design of a world picture was bright and bold. The architect had managed to engrave and set the world within the Church, while simultaneously portraying the Church as a base from which to change the world. In the first four months alone, some 50,000 curious visitors streamed through to see the “world in color.” Many found the experience to be slightly surreal, even religious. “You enter in the Old World, just east of Africa, cross the glass bridge to the New World, and exit just west of the Americas,” one reviewer explained. “With the ocean below your feet, it’s like walking on water.”[x] Mapparium readers have been generous and creative in sharing the social meaning of the map’s image. Often it serves as a physical reference point for bygone lands, places only half-imagined from family stories. The poet Susan Rich saw Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia—“lands my grandmother left”—and planted herself to read the map: “Feet to Antarctica, arms outstretched / like beacons toward Brazil; / I’ll take this globe as my own.”[xi]

NEXT: Mapparium visitors were often moved to comment on the act of reading the map. But were they also moved, as Church leaders intended, to join the world mission of Christian Science?

[i] Thanks to Raymond Haberski, David Mislin, and Rachel Gordan for helping me think through this topic during our panel at the S-USIH 2017 annual meeting in Plano, Texas.

Blueprints and site plans for the Mapparium and The First Church of Christ, Scientist, dated 20 Feb. 1933, 30 March 1933, 4 May 1933, 3 Aug. 1933, Organizational Records of The First Church of Christ, Scientist, 1933-1936, The Mary Baker Eddy Library, Boston, Massachusetts.

[ii] Chester Lindsay Churchill to F.M. Lamson, chairman of Publishing House Building Committee, 6 July 1933, Organizational Records. Biographical information on Churchill (1892-1958) is scarce. A 1914 alumnus of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, he returned from service in World War I and opened an agency at 9 Newbury Street in Boston, roughly a five-minute walk from the Mother Church site. His other prominent commissions included Liberty Mutual Insurance Company’s home office at 175 Berkeley Street, as well as the terminals and headquarters for Pan American World Airways in Queens, New York.

[iii] David Woodward, Catherine Delano-Smith and Cordell D. K. Yee, Plantejaments Objectius d’una Història Universal de la Cartografia / Approaches and Challenges in a Worldwide History of Cartography (Barcelona: Institut Cartogràfic de Catalunya, 2001).

John N. Feaster, “Highways in Our Minds,” Wisconsin Congregational Church Life 61 (1942): 28-29.

[v] John Rennie Short, The World through Maps (New York: Firefly Books, 2003), 160-217.

[vi] Gary S. Dunbar, ed., Geography: Discipline, Profession, and Subject Since 1870 (Norwell: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001).

[vii] Churchill, Report of conference with Publishing House Building Committee et al., 10 Jan. 1935, Organizational Records.

[viii] Churchill, Report of conference with Publishing House Building Committee et al., 10 Jan. 1935, Organizational Records. Churchill’s scale was “Approximately 22 statute miles to the inch,” with map signs (which Churchill called “symbols”) for national and state capitals, national parks, passes, and canals.

[ix] Churchill to Lamson, 3 April 1935, Organizational Records.

[x] “Global View,” The Washington Post, Nov. 18, 1990, E1.

[xi] Susan Rich, “The Mapparium,” The Cartographer’s Tongue: Poems of the World (Buffalo: White Pine Press, 2000), 18.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Sarah,

When I was in high school in Connecticut in the early 1970s, my American Studies class went on a Field Trip to Boston. In retrospect, our itinerary seems rather bizarre: Paul Revere’s house, the site of Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond (in nearby Concord), the wax flower collection at Harvard, the observatory atop the Prudential office tower, and the Christian Science Mapparium (that term wasn’t used; we called it the hollow globe). Our teachers never explained the reason for visiting either the Mapparium or the wax flower collection—neither had any connection to what we had been studying, and, being typical high school students, we never asked for one. My best guess: it was an interesting curiosity. I haven’t thought about it since! Thanks for jogging my memory.

Sarah, you probably already know this reference, but Jhumpa Lahiri’s short story “Sexy” locates a few short scenes in Mapparium. I’ve always taught those sections in relation to mapping as a metaphor, so I’m especially grateful to have a material and political history to go along with the fiction!