The Book

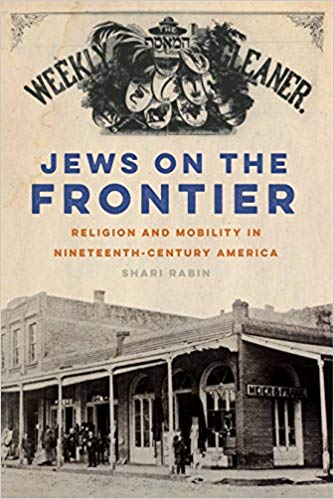

Jews on the Frontier: Religion and Mobility in Nineteenth-Century America (New York University Press, 2017)

The Author(s)

Shari Rabin

In Jews on the Frontier: Religion and Mobility in Nineteenth-century America

, historian and religious studies scholar Shari Rabin explores Jewish Americans who were not necessarily devout as they traversed boundaries within the United States. Many were immigrants, and most passed as white as they navigated their own freedom in a nation that privileged whiteness and did not restrict minority religions in the ways that Europe did. Rabin opens her introduction with a vignette about a Jewish American man named Edward Rosewater, who roamed the Midwest in the 1850s, learning to work the telegraph. Violating his own Saturday Sabbath, Rosewater was neither an evangelical Christian nor a Saturday-observer rebelling against the Sunday-observing majority. Accordingly, Jews on the Frontier

argues that Rosewater’s “case is not a peripheral one of religious deterioration through secularization, Protestantization, assimilation, or apathy. Rather, he is an exemplar of American religion, albeit not as it is typically understood” (2). Rabin claims culturally Jewish travelers as a legitimate instance of American religion, while also bridging the gap between Jewish studies and early American religious historiography.

For anyone interested in early American Jewry, Rabin teaches readers about these people and how they constructed their identities. She writes: “For most Jews, the relationship between Judaism and American mobility was a fraught one that occasioned debate and inspired adaptations. These Jews did things like eat non-kosher beef but not pork, eschew congregational membership but live in a Jewish boardinghouse, or marry a non-Jewish woman but insist that their children were Jewish” (5). Specific examples of each of these contradictions populate the book.

Spanning the nineteenth century, Rabin organizes her book thematically. Three sections – “Movement and Belonging,” “The Lived Religion of American Jews,” and “Creating an American Judaism” each contain two chapters per section. Chapter one, “Wandering Sons of Israel,” contextualizes Jewish-American mobility as a “newfound right” in contrast to Europe (13). In this opening chapter, Rabin deeply engages the relationship between religion and ethnicity, as well as both religion and ethnicity’s ties to the state. Chapter two, “Reminding Myself That I Am a Jew,” argues that “the shock of migration was only the first in a series of negotiations of home, place, self, and other as they moved throughout the United States” (31). Chapter three delves into Jewish family life, analyzing Jewish laws and rituals beside American laws and rituals to reveal the mobile Jewish experiences of life cycle events. Chapter four focuses on material culture and popular theology, and chapter five analyzes the “mobile infrastructure” of Jewish American religious communities and synagogues (103). Finally, chapter six, “The Empire of Our Religion,” cements the idea of “far-flung Jews creating community and identity on the road” (123). Collectively, these chapters reveal what chapter six calls an “emerging mobile imaginary of American Judaism” (123). This meant that they perceived collective identity through communities and rituals across distances.

One accomplishment of this book is that it spans geography. Rabin executes this through a wide range of sources: family papers from the American Jewish Archives (AJA), Jewish sermons also available at AJA, Isaac Leeser’s unwieldly correspondence and his newspaper, The Occident, plus other newspapers, court cases, federal records regarding citizenship, census records, and more. The fluid geography of this study reinforces the importance of its topic and the spirit of mobility.

Rabin’s book is not the first monograph in Jewish studies to have the title, Jews on the Frontier. Historian-Rabbi I. Harold Sharfman’s 1977 book Jews on the Frontier argued that Jewish pioneers assimilated rather than maintaining their religion during westward expansion, noting that Jewish Americans disappeared as unnamed peddlers in the historiography. Rabin directly counters Sharfman’s interpretation, framing the complexities of Jewish cultural and religious identity as an “exemplar” of American religion (2). Although Rabin and Sharfman addressed the idea of mobility through many of the same people and phenomena, culminating in their shared title, they define religion completely differently. Historiography is moving past the sacred versus secular binary, and Rabin’s Jew’s on the Frontier epitomizes this step. Rabin’s approach seems more useful for avoiding a Christian-centric framework when studying American Judaism. Beyond travel stories, historians Dianne Ashton and Lance J. Sussman each offer monographs on early American Jewish history through the central characters of Rebecca Gratz and Isaac Leeser respectively.

At the same time, Rabin advances scholarly understanding of church-state issues in American history by bearing out the stories of religious minorities negotiating moral authority. The problem of Sunday laws was a key issue that emerges from Rabin’s study. During the Jacksonian era, thousands of evangelical Christians campaigned through petitions and other grassroots activism for the federal and state governments to honor Sunday as the Sabbath. The resulting “Sunday closing laws” economically disadvantaged Jewish Americans and other Saturday-observers because if your religion prohibits you from working on Saturdays, and your government prevents you from working on Sundays, then you get to work and earn money for one fewer day every week than the majority of Americans (27). This was an era before the contemporary notion of a weekend.

This ambitious and masterful monograph transforms the idea of mobility, which once suggested assimilation, but Rabin complicates it. Jewish Americans enjoyed a right to move from place to place in America that most of them, particularly immigrants, had not previously experienced. They honored Jewish life cycle events, including birth, marriage, and death to the extent that they could while on the road. They benefitted from perceived “whiteness” both legally and societally in the United States. Ultimately, a central takeaway from Rabin’s Jews on the Frontier is that American Judaism was not limited to the northeast and was definitely not limited to the late-nineteenth century wave of Jewish immigrants. She dismantles the framework that assumed Sabbath observance was devout and normative, while non-observance was cultural or assimilated, arguing instead that these improvisational practices were the norm, not an outlier.

About the Reviewer

Rebecca Brenner is a PhD candidate in history at American University in Washington, DC. She earned her BA in history (honors) and philosophy from Mount Holyoke College and her MA with a concentration in public history from American University. Her dissertation, tentatively titled “When Mail Arrived on Sundays,” asks what Sunday mail delivery meant for moral authority and the political economy from 1810 through 1912, focusing on religious minorities and disenfranchised persons. In addition to USIH, her sites of publication include Black Perspectives and The Washington Post.

0