The Book

Before Chicano: Citizenship and the Making of Mexican American Manhood, 1848-1959. New York University Press, 2018, 280pp.

The Author(s)

Alberto Varon

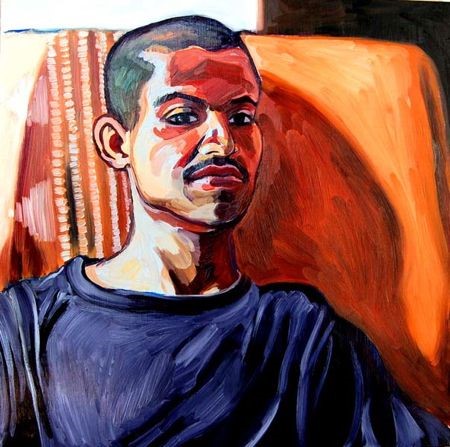

[Rebeca García-González, Defiant/Desafiante, oil on birchboard, 2017

Personalities, complex and contradictory, that too often are missing from national debates about the border and the contributions of immigrant labor to our society. The artists, working within the traditions of the Chicano arts movement, want to make sure we remember every story is about human beings. If you see a person instead of a “problem,” the character’s ideas and feelings might connect with yours. If an artist’s illusion works, the people they reveal can’t help but surprise us with needs and demands, including claims actionable in the courts and through the political process. Which we might understand as reasonable and support if only because societies are healthy only to the degree that all citizens, current and potential, enjoy equal rights.

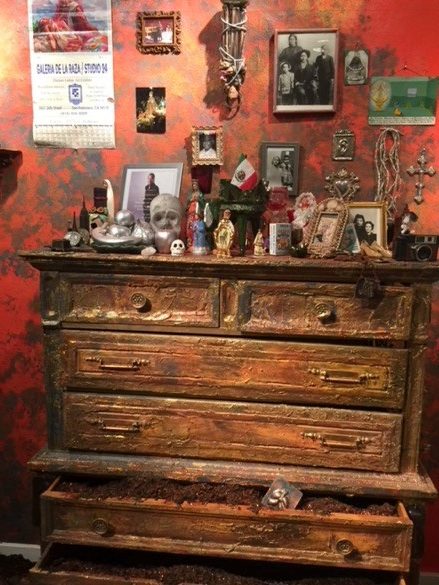

Fifty years ago, Amalia Mesa-Bains was one of the pioneers of the emerging Chicano arts movement, one of hundreds of artists, writers, musicians, filmmakers, and performers producing work celebrating of Mexican culture within the United States while publicizing and supporting the community’s struggles for justice and equality, like those of the United Farm Workers to secure the same rights as other workers in the United States. Visual artists were often the most visible because wherever there were Mexican communities north of the border, Chicago and Detroit as much as San Francisco, San Diego, or El Paso, they made murals to tell of the stories of la Raza (“the people”) and of nuestra América (our America).

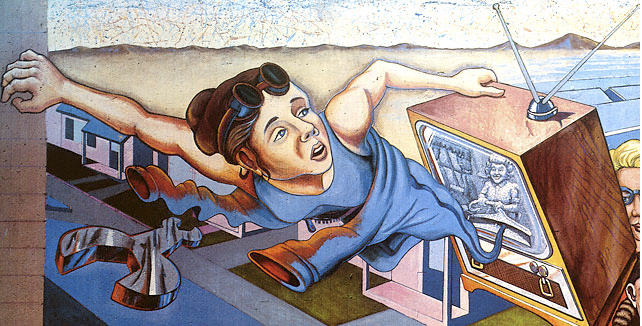

In San Diego, the murals at Chicano People’s Park were a guerrilla action that young artists in the Barrio Logan Heights created to support the community as it converted empty land into a park that the city refused to build. In Los Angeles, Judy Baca worked with four hundred teenagers and their families to paint The Great Wall of Los Angeles, a mural extending six city blocks along a culvert that retold the history of California as experienced by the state’s racialized communities. The great murals of the Mexican Revolution painted in the 1920s by Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and dozens of others inspired the work of young Chicano and Latino artists working in the United States as their communities stood up as citizens whose rights preceded and would outlast the policies and customs that made them valuable to the economy but politically expendable. So the community would not forget how deep its roots were in the American land, new murals retold the stories of the Aztecs and Mayas as well as the continuing struggle in Mexico for independence and self-sufficiency. The work however was as diverse as the communities where the new arts movement took root. The Great Wall of Los Angeles started its history with the first occupants of Los Angeles, the Chumash, and their struggles with Spanish and Yankee invaders. The Great Wall linked Mexican Los Angeles to the experiences of the Chinese, Japanese, and African American communities, recovering the centrality of people of color within the long history of the labor movement in the city.

Community-based art affirmed the importance of cultural work for those whose fight started by refusing to be invisible. Funding was and remains limited, but rasquachismo (from rascuache, poor, penniless, wretched, in bad taste) became the basis for an aesthetic that accepted working with and often repurposing whatever was available as consistent with the ethos of poor, subaltern communities. Using whatever is at hand for the task at hand has long been a way of life in Mexico and Central America. That elites ridicule the poor for their strategies to make their lives workable reinforced the attraction of improvisation for community-centered artists.[1] Getting the job done is more important than technical bravura. If all the resources needed for creativity are always at hand, then “lack of resources” is never be a reason for not creating. The goal remains creating experiences that make present human beings who have been invisiblized.

Scholars of Chicano culture have generally considered Pocho, José Antonio Villarreal’s semi-autobiographical novel about growing up the son of Mexican immigrants in a California town, the first public expression of Chicano aesthetics. The novel, published by Doubleday in 1959, fit into a genre popular in the mid-twentieth century of accounts by young men from “ethnic” communities narrating how they creatively adopted to a hostile society by reimagining who they were and who they could become. (Other authors who contributed one or more books to this genre include Carlos Bulosan, John Okada, John Fante, A. I. Bezzerides, Alfred Kazin, and arguably Jack Kerouac.) The novels generally showed assimilation into the United States as the country actually operates was (is) impossible. This is true even when the main character has options—in Pocho, the local police department wants to recruit the hero because they need an officer who “knows” the barrio. He decides instead to join the military and then use his GI benefits to go to university. Alberto Varon notes in his new book on Mexican writing in the United States before the Chicano movement that when Pocho appeared, important earlier works either were long out of print or had never found a publisher. Pocho filled a void and did so by insisting that young Mexicans in the United States had to create their own lives on their own terms. Villarreal’s story underscored that personal autonomy was not identical with self-aggrandizement but indeed essential to the liberation of the community. From that perspective, the novel might be seen as an expression and affirmation of mid-twentieth-century liberal views prioritizing personal development. The most radical aspect of Pocho was Villarreal’s portrayal of women and homosexuals as strong characters with the best understanding of how to survive in a hostile world, if only because their marginality has forced them to question social conventions. Without having learned from the women and gays he met, the novel’s protagonist would have been stuck trying to live up to expectations that he could not fulfill.

As the Chicano movement grew, resurgent activism inspired many more books, but Pocho retained its status as a milestone announcing a still-unfolding revolution. The language was eloquent, filled with heartfelt evocations of Mexican family life and of the fraternal bonds confused young men from working-class backgrounds form to fit themselves into a society their parents cannot understand. By the 1970s, the book, ambiguous as to the importance or the value of Mexicans remaining in autonomous communities, fell out of favor with Chicano activists, though a reissue of the book in 1971 and marketed as the classic Chicano novel sold very well. Growing up in a pan-Latino, pan-ethnic, indeed pan-racial environment, Pocho’s protagonist sees his father’s intense cultural separatism as irrelevant to political and economic life in the United States, not a source of pride, but an obstacle that the family needed to overcome.

[Amalia Mesa-Bains, Emblems of the Decade: Borders/Emblemas de la Década: Fronteras, mixed media installation, 2015-2018]

Villarreal’s figurations of sexual and gender politics predate vigorous debates within the Chicano movement on machocentrism during the 1980s and 1990s. Varon argues that Pocho is better understood within a longer frame of writing by Mexicans within the United States reexamining the relationship of manhood and citizenship as a necessary part of their struggle for full participation in U.S. society. The novel’s perspectives drew upon to older republican understandings of citizenship developing since the U.S. conquest of northern Mexico that synthesized diverse figures from both English- and Spanish-speaking America. Writers, whether working in English or Spanish, turned to Thomas Paine and Ralph Waldo Emerson for strategies for how to contest exclusion as well as Pancho Villa and José Martí, plus many lesser known figures who were important locally. The innovation in political thinking that makes Pocho a particularly interesting text sixty years after its publication was the author’s prefiguration of queer theory and queer politics. In effect, Villarreal revealed that how Mexicans in the United States understood their fight for autonomy and inclusion prepared the ground for a radical critique of male supremacy and heteronormativity that remains relevant to national political struggles. Villarreal’s book dramatizes a moment when new social movements emerged to offer alternative visions of liberation instead of repeating the tropes of nationalism and class struggle that overdetermined political struggle for the previous century.

[Judith Baca & Social and Public Art Resource Center, panel from The Great Wall of Los Angeles, 1978]

A chapter I found particularly interesting examines unpublished novels from the 1930s by Américo Paredes, one of the most important folklore scholars of the mid-twentieth century, and Jovita González, an educator primarily known for the textbooks she wrote for Texas history classes. Varon argues that these missing works, not in print until the 1990s after young scholars discovered the manuscripts in the personal papers of the two scholars, reveal a new concept of “economic citizenship” transforming how mid-twentieth-century Mexican American civil rights activists reframed politics. Paredes and González were part of a new professional middle class, influenced by early twentieth-century feminism as well as pragmatism, that challenged older leaders whose authority rested on land ownership. Their novels developed in-depth critiques of the self-governing male who could defend his property “with a pistol in his hand” but whose political potential was sharply limited given that his interests had little in common with those of the hundreds of thousands of men and women who came north to work in the fields, the factories, the mines, and on the railroads. Economic citizenship required new modes of organization, including trade unions, and accepting that women worked outside the home. Varon argues that the texts, even if unpublished, are evidence that long before the rise of the Chicano movement, important figures in the community understood that cross-gender collaboration was politically necessary even if contrary to conservative but widespread conceptions of lo mexicano.

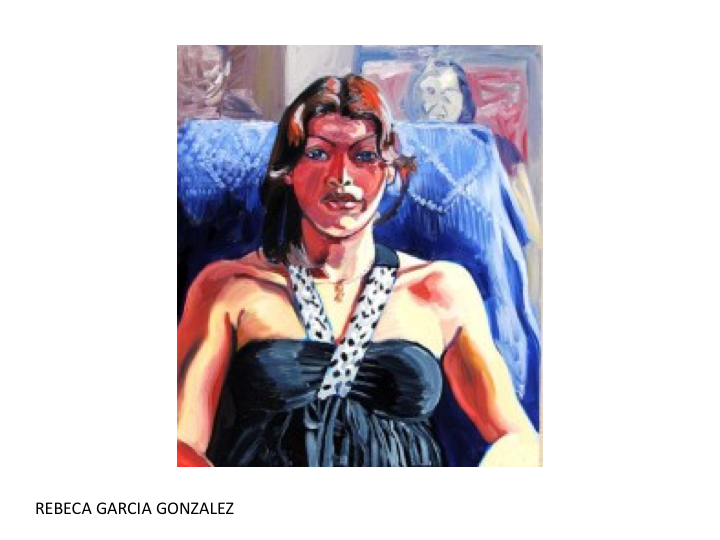

[Rebeca García-González, La Nicaragüense/The Nicaraguan, oil on canvas, 2008]

When the Chicano cultural movements began more than a half century ago, the writers and artists involved believed that their work was an essential contribution to imagining a society based on equality instead of exclusion. The events of the last sixty years affirm the continuing need for keeping community roots alive and supporting the faith of people in their ability to solve their problems themselves with their own resources. They also show a community struggling to develop a more capacious view of who belongs. For the nation at large and for the community as an autonomous but integral microcosm, the temptation remains to reduce persons to a few simple labels representing the functions they serve—this one’s a worker, that one must be criminal, here’s a victim. This one is a fighter and a father, a proper leader; that one is queer, not one of us. The work Varon surveys points to another model: citizens standing before each other face to face, listening hard to what another person has to say before speaking their piece, identifying where they agree and disagree, perhaps most important if they are to find a starting point for solving common problems, acknowledging everyone contributing to society is a fellow citizen.

[1] The classic texts on rasquachismo are Tomás Ybarra-Frausto’s “Arte Chicano: Images of a Community,” in Signs from the Heart: California Chicano Murals, eds. Eva Sperling Cockcroft and Holly Barnet-Sanchez (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993), 54-67, and “Rasquachismo, a Chicano Sensibility,” in Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation, 1965-1985, eds. Richard Griswold del Castillo, Teresa McKenna, and Yvonne Yarbro-Bejarano (Los Angeles: Wight Art Gallery, University of California, Los Angeles, 1991), 155-162. See also Amalia Mesa-Bains, “Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicano Rasquache,” Aztlán 24 (1999), 157-167.

0