Memorial Day weekend brings tourists from across the country to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Desire for air conditioning, a bathroom, or water entice even more visitors from outside. Smithsonian American History engages visitors from a wide range of backgrounds and perspectives. A new exhibit, “All Work, No Pay

,” curated by historians Kate Haulman and Kathleen Franz

, argues that women throughout American history have deserved pay for domestic labor. Located toward the center of Smithsonian National Museum of American History’s ground floor, beside the Batmobile, “All Work, No Pay” catches tourists’ eyes with artifacts of women’s clothing, protest memorabilia, and a bright teal backdrop.

On the far left, the title “All Work, No Pay” occupies a speech bubble above the introductory panel, “American women have always worked, but their work in the home is often unpaid and invisible. One way to see this work is through what women wore.” The exhibit uses clothing artifacts to document: “This labor – cleaning, cooking, child rearing, and other care work – fused with notions of what it meant to be a woman and shaped Americans’ ideas about work, gender, and clothing.” Indeed, this bright, centrally located exhibit shapes the ideas of tourists from across America regarding women’s work and pay, or no pay.

The first panel, “The Good Wife,” located on the far left, introduces the “good wife” from Revolutionary America and the “angel in the house” from the 1830s, displaying their clothing to illustrate. For instance, the “short gown” from the early republic clothed “all kinds of women… from free women of middling status to enslaved women.” The exhibit clarifies that “someone, often enslaved or servant women, performed the strenuous and invisible work of the home.” By introducing the “good wife” and “angel in the house” tropes without reducing them to the “separate spheres” oversimplification, while explaining that the women who performed the most strenuous unpaid labor were enslaved, panel one teaches an accurate, important story of the early United States.

Following more nineteenth-century artifacts, panel two skips to the 1920s through 1940s, a transformative time for women in the United States, owing partially to having recently attained the right to vote. This panel, “Turning Unpaid into Paid Work,” quips that work “persisted unpaid and often invisible unless left undone,” thereby underscoring the imperative nature of women’s labor. Objects here include the electric iron, as well as a plethora of advertisements and posters seeking women to perform domestic labor for pay, albeit low wages.

The final section of the mail wall, entitled, “The Second Shift,” uses clothing and artifacts from the 1960s through the 1990s, culminating in contemporary “athleisure” yoga pants. According to the exhibit, “higher education, second-wave feminism, and thee economic downturn of the 1970s all led to the widest swath of women moving into the paid workforce. Among them were middle-class married women with children.” While low-income and minority women worked for wages throughout American history in most cases, the socioeconomic influences mentioned by the exhibit expanded the workforce to middle-class women, who drew further attention to feminist demands.

In the 1970s, some newly empowered women distributed buttons to support “wages for the household.” The exhibit asks, “which button would you choose,” prompting visitors to interpret their own lives as a part of this history. A central takeaway is that domestic labor merits compensation. Printed speech bubbles on an adjacent table ask, “Do you pay someone to do housework and childcare? Why aren’t wives and mothers paid for this work?” And “Who did the work in your mother’s house? In your grandmother’s house?” The speech bubble aesthetic announces that working women – paid, unpaid, and both – have something to say and demand to be heard.

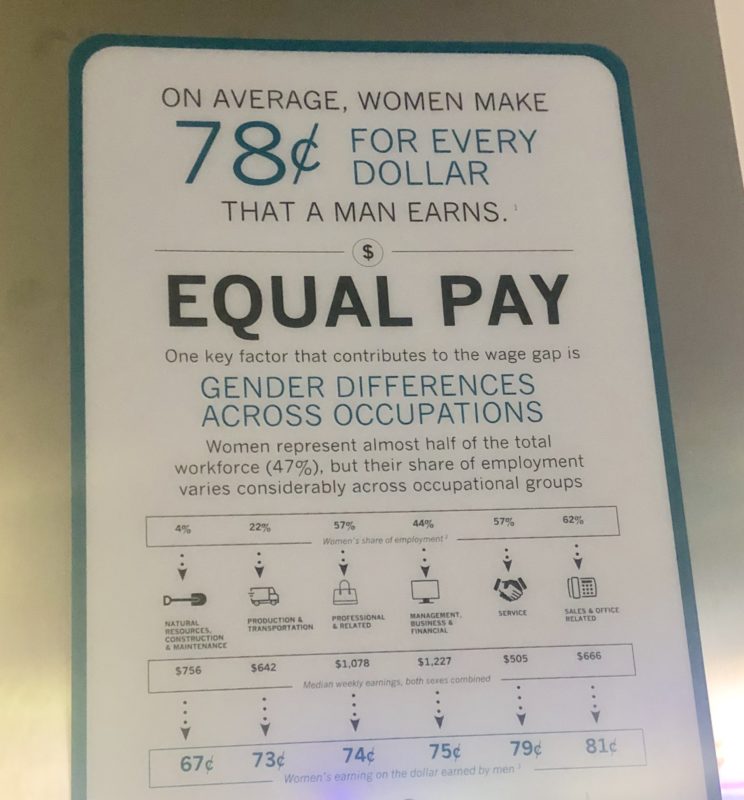

Franz and Haulman’s “All Work, No Pay” exhibit invites women to expect equal pay for all kinds of work and to imagine their own places in history. An adjacent wall announces, “On average, women make 78 cents for every dollar that a man earns.” I include an image below, rather than quoting all the details from this informative poster. Conservative media online, which some MAGA-hat-wearing tourists and visitors likely consume, denies any gender pay gap currently exists.

From “All Work, No Pay” exhibit at Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Photo by Rebecca Brenner, 26 May 2019

Overall, the “All Work, No Pay” exhibit transformed my understanding of feminist economics, previously informed by philosopher Linda Hirshman’s book, Get to Work and Get A Life Before It’s Too Late. Hirshman aims to empower women to pursue rewarding careers, denouncing the tendency of highly educated, privileged women to be homemakers. She particularly addresses the women who can afford the option of staying home. Building a philosophical argument, Hirshman concludes that women assigning the private sphere to only themselves is unjust.[1]After reading Get to Work and Get A Life Before It’s Too Late in 2013, I believed that working a job outside the home was necessary for the advancement of all women, until I visited “All Work, No Pay” in 2019. I still plan to work outside the home and probably leave too many household tasks to my partner. However, the exhibit convinced me that women’s household duties throughout American history qualify as work and deserve recognition through compensation.

In 2006, Hirshman appeared on The Colbert Report to discuss her book. Colbert facetiously suggested, “All the women in the world just shift one house over and raise the children next door and get paid for it. It’s their job. Then they get home at night,” to which Hirshman did not miss a beat: “If we did that, at least the women who did that would get social security when they got home.” She might agree with the exhibit, but for the purpose of my development of feminist ideas, “All Work, No Pay” persuaded me that my own takeaways from Hirshman’s book were limited.

Notes

[1]As an undergraduate, I distilled Hirshman’s argument for a women and philosophy class: 1. The private sphere involves repetitious socially invisible, physical tasks [Assumption]. 2. Flourishing involves exercising intellectual capacities, autonomy, and contributing positively to the world [Assumption]. 3. The private sphere allows for fewer opportunities for full human flourishing [1, 2]. 4. The private sphere is not the natural or moral responsibility of only women [Assumption]. 5. If something is bad for you, and it is not only your responsibility, then it is unjust to make only you do it [Assumption]. 6. If some situation provides few opportunities for flourishing, then it is bad for you [Assumption]. 7. The private sphere is bad for humans [3,6]. 8. The private sphere is not the natural or moral responsibility of only women and the private sphere is bad for humans [4, 7]. Assigning the private sphere to only women is unjust [8, 5]. 10. If it is unjust for an outside force to assign you to do something, then it is unjust for you to assign yourself to it [Assumption]. 11. Women assigning the private sphere to only themselves is unjust [Conclusion].

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this, Rebecca! I’m not familiar with Hirschman’s book, but I’m really intrigued! Does she engage with Charlotte Perkins Gilman at all? Or any other feminists who have sought to force the recognition of the value of domestic labor performed in one’s own home? I’m thinking of, for instance, the feminists in Delores Hayden’s The Grand Domestic Revolution, or the more recent Wages for Housework movement, led by Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, and Silvia Federici?