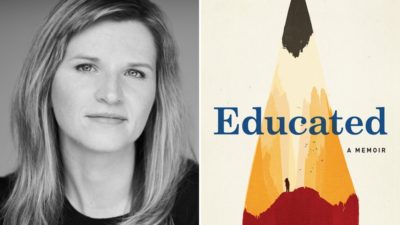

Courtesy of Bustle

A bestseller by an intellectual historian has been hiding in plain sight for the past year—did you know?

Tara Westover, whose memoir Educated

was prominently included in many “Best of 2018” lists, took her PhD from Cambridge, where she studied with David Runciman and completed her thesis in 2014, titled “The Family, Morality, and Social Science in Anglo-American Cooperative Thought, 1813-1890.” Westover in fact discusses her PhD work quite a bit in the later chapters of the memoir, and the book as a whole eloquently attests to the joy of roaming through the history of political and social thought. One of Westover’s lodestars is John Stuart Mill, and like Mill’s Autobiography, Educated

is an argument that certain ideas can fundamentally change a person from the very moment they first encounter them.

I offer this reflection on one of the book’s themes, then, to draw intellectual historians’ attention to this book: it is, after all, not every day that we get to see one of our number on the bestseller list.

***

Most of the attention given to the book has focused (quite naturally) on the resilience and intellectual growth that Westover displays throughout its pages. For those who are unfamiliar with its basic story, Westover grew up in a family of Mormon survivalists in Idaho. Her parents radicalized over the course of her childhood: some of her older siblings went to public school and the family lived fairly similar lives to other denizens of the sparsely populated Franklin County. By the time Tara was of school age, however, her father had become convinced that any kind of exposure to government programs was equivalent to surrendering to socialist brainwashing—in fact, in his mind, formal education of any kind was liable to seduce and corrupt, as he considered even the LDS-run Brigham Young University dangerous.

Westover did, however, end up attending BYU, and while there she discovered how much of the world had been hidden from her. She mortified herself by asking what the Holocaust was in an art history class, for instance, and was staggered to learn about the US civil rights movement. While at BYU, she got into an exchange program at Cambridge, and impressed some of the faculty there enough to be admitted later into the PhD program after she graduated college.

Retelling the book as a succession of intellectual achievements, however, does not really reflect the true emphases of the book. For a memoir titled for and ostensibly about the growth and liberation of the mind, Westover’s narration is relentlessly corporeal, even carnal. She and her family are constantly getting injured, experiencing pain, and performing dangerous manual labor. Her father makes his living selling scrap metal and building barns and other outbuildings on the farms of the area, and his children all work by his side from an early age. Her mother becomes first a midwife and then an enormously successful manufacturer of homeopathic remedies. Westover also recounts in detail the extreme physical abuse she suffered at the hands of one of her brothers—a history of violence that ultimately causes her to break with her parents when they refuse to believe her about the abuse.

Injuries affect all parts of the body in the memoir, from the toes to the wrists. But head traumas are more common than any other injury, and they occur to nearly every family member. There are two major car accidents in the book, one of which (Tara speculates) caused permanent brain damage for her mother. A fall off a forklift and a motorcycle crash leave one brother with his skull cracked open. Even her grandfather lives much of his life with a metal plate in his skull, thanks to a mishap at work. And Tara herself seems to sustain concussions a few different times over the course of the book.

Westover treats these episodes with caution, but she underlines the severe aftereffects of these traumas: they become part of the mental and emotional world of the people who suffer them as much as they persist as chronic headaches and other physical symptoms. Behavioral changes, cognitive impairment, mood swings, and other similar experiences become cornerstones of interactions between family members—all thanks to these brain traumas.

Obviously, these were real and quite significant events in the Westover family’s history: Westover was not being artful in including them, as if she were trying to make some kind of statement about the mind-body problem. But it is worth thinking about the way Westover’s experiences and the record of those experiences points to the way that neurological traumas or abnormalities have taken on an increasingly explanatory role in society, sliding into some of the functions that older Freudian theories once filled.

Intellectual history—and especially the history of ideas—does not seem well prepared to deal with the increasing prominence of concussions, CTE, etc. in public discourse. It is not just that intellectual historians take for granted that their subjects’ brains were undamaged. It is also that there doesn’t seem to be any way that intellectual historians can respond productively to new research about brain trauma, assimilating the changing popular and scientific understanding of its significance in thinking about the ways that ideas are conceived, communicated, received, interpreted, etc.

To put the point more simply, it is difficult for me to picture what intellectual historians might actually learn from studies of brain trauma and how we could factor it in to our research in anything other than a totally reductive and mechanical manner. There may not even be much desire to do so, but the precedent of Freudianism does demonstrate the way that new ideas about normal and abnormal mental activity has enriched intellectual history before.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Seems to me that intellectual history, as it embraces embodiment, is going to have to spend some time learning from disability history, or at the very least learning that disability studies generally, and disability history specifically, already exists as a discipline.

Jonathan, thank you for this comment. Whose work do you think would be a good entry point for intellectual historians in particular to learn from disability studies / disability history? I think it’s safe to say that intellectual history on the whole or as a whole (and that’s a heuristic construct, of course) is probably not going to embrace embodiment, but I suppose within the discipline writ large, there might be a “school” that does foreground the fact that all ideas are necessarily embodied. I suppose I am part of that school, which may imperil my membership in some other school or schools, if membership is dependent upon a foolish consistency.

It’s not really my field, and while I have interests in this regard, TBI and related topics isn’t something I’ve seen addressed historically. I know who I would ask on twitter, but I’m certainly not going to bother Dr. Seal with this any further.

I definitely take your point, Jonathan, but is the problem really ignorance? That is, are intellectual historians trying to solve a problem for which disability studies has a good answer, and intellectual historians are just overlooking it? I’m not sure that’s the case.

Part of the issue may be the resistance to embodiment, certainly, but I think the truer aversion is to impairment, particularly cognitive impairment. It is, I think, relatively easy to imagine an history of Deaf intellectuals, or of Disabled activists and organizations in the campaign for the ADA. But I think intellectual historians would struggle to keep the focus on individuals with acute or chronic cognitive impairments in an intellectual history of, say, concussions. Instead, the scholarship would (I imagine) tend to gravitate toward the way non-impaired actors defined, studied, treated etc. the condition. We can see this tendency already in scholarship on eugenics and intelligence testing, which has generally sought to explain (and critique) the goals and worldviews of the people administering the tests or espousing eugenics rather than the people who were classified as unfit.

Or take the way neurasthenia is generally treated by intellectual historians–it is typically examined for what it tells us about the cultural and spiritual anxieties of figures who either formulated it as a diagnosis (like George Beard or Silas Weir Mitchell) or who suffered from it but overcame it sufficiently to examine it from a restored perspective (like William James). The experience of people who were diagnosed as neurasthenics tends to be subordinated to these larger narratives about ambient anxieties about industrial civilization or the hollowing out of Christianity or what have you. Intellectual historians prefer the unimpaired but anxious every time, I think, over the impaired and less articulate.

The only way to deal productively with brain injury or trauma is to have a diagnosis by a qualified medical practitioner. Otherwise, it’s merely projection, or speculation. So intellectual historians can cross the bridge when their subject(s) have confirmed expert diagnoses. Our “patient” history should dictate how we explain the topic in terms of ideas in a contextual space. We work on best available medical science.

Otherwise, we can question, as a subject, the development in medical history of how those injuries are assessed and how diagnoses are constructed. Is the medical science plausible and based on scientific consensus, or operating on the fringe, with minimal consensus?

Otherwise, thanks, Andrew, for bringing this bio to my/our attention! – TL