Editor's Note

For previous entries in this series on cosmopolitan Christianity in early America, please see: The Christian and the Cosmos; The Puritan’s Grand Tour; The Preacher and the Pope; The Best of Both Worlds, 1853.

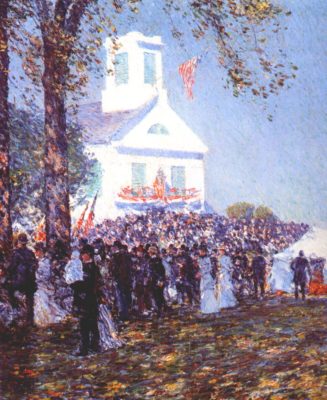

Childe Hassam, “Country Fair, New England” (1890)

Floating between Notre-Dame’s grandeur and the frozen dance of Ice Age mummies, Harriet Beecher Stowe saw that travel wearied even the most ardent American pilgrim. Like Horace Bushnell, she found that surveying the breadth of Europe’s religious art and culture left her astounded and exhausted. Her heaps of books had not wholly prepared her for the trip. The dingy clank of half-preserved martytrs’ cells in Germany, the soaring spirituality of glittering Alpine glaciers, the new British Parliament building’s sprawling rise—none of it echoed exactly with what she knew of the world before she began canvassing the Continent in 1853. Halfway through writing her travelogue/antislavery tract, Sunny Memoirs of Foreign Lands, Harriet Beecher Stowe dipped into a ruefully cosmopolitan tone. In some encounters, she thought, the “ideal had outstripped the real.”

Take Stowe’s first-ever Roman Catholic service in Paris’ lavish Notre-Dame Cathedral. Bellowing organ music and leaden incense gave her a violent headache. In her religious truths, Harriet felt unswayed. “It ought to be impressive here, if anywhere,” she wrote of mass at Notre-Dame. “Yet I cannot say I was moved by it Rome-ward. Indeed, I felt a kind of Puritan tremor of conscience at witnessing such a theatrical pageant on the Sabbath.” She lamented the kind of Catholicism at hand in the cathedrals of Strasbourg and Cologne, where “idolatrous” petitioners knelt numbly at shabby devotional shrines. While their worship aesthetics failed to impress, Stowe’s conversations with Parisian Catholics convinced her that, for many, true religion was a “real and vital thing.” She grew willing to accept certain parts of Catholic practice, if not the overarching theology. Firmly, she believed that promoting anti-Catholicism would warp Protestant intellectual life. So Harriet weighed the merits of incorporating, carefully, shards of Catholic ideas into her worship. “I have often thought that, in the reaction from the idolatry of Romanism, we Protestants were in danger of forgetting the treasures of religious sweetness, which the Bible has given us in her brief history,” she wrote. The key was to practice “loving without idolizing.” Harriet gifts scholars with a great insight here: Most laypeople learn more about new religious ideas from each other, than they do from a chance mass or a few words from the pulpit. Before and after Harriet’s day, lay dialogue remains the great educational engine of faith formation.

In any pew, the practitioner’s mind runs along multiple tracks. For historians, that means digging into the aesthetic landscape that Stowe encountered, and then charting all “the places in between” that her mind turned. As she listened to the chant and flow of vespers at Notre-Dame, Harriet reflected that John Calvin’s influence would persist in Scotland and America, “because the great fundamental facts of nature are Calvinistic, and men with strong minds and wills always discover it.” The faithful bent to history. They were not devoted, however, to honoring all of it. Like Stowe, they matched up the intellectual seams of what they read with what they experienced. At times, Stowe sounded like a sociologist of religion. In France, for example, she identified “three forces which operate in society: that of blind faith, of reverent religious freedom, and of irreverent scepticism.” Stowe realized that Old World Christianity held vital lessons to impart through art. Two paintings that she thought “sublimely matched” in depicting the interplay of sin and civilization were Thomas Couture’s Romans During the Decadence (1847) and Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819). The lush hedonism of Couture’s pre-Christian scene, Stowe wrote, should hang in the U.S. Capitol as a caveat to citizens.

Childe Hassam, “Church at Old Lyme” (1905)

Deftly, Sunny Memories reveals how much of New England Stowe rediscovered abroad. Alpine neighbors were just as nosy as friends in Andover. Drowsy Scottish children drifted off during church. Swiss farmers prized homespun frugality just as much as their Yankee cousins. Even Rembrandt van Rijn’s masterpieces garnered a New England corollary in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s literature. Toiling two centuries apart, both artists threw light and shadow to create “a somber richness and a mysterious gloom,” she wrote. Armed with her Sunny Memories and a fresh stockpile of global church history, the cosmopolitan Stowe settled into writing Oldtown Folks

in 1866. She had the base mixture for her characters and the guts of a good story: local parish drama and the “austere and terrible problems” that afflicted “every thinking soul.” That last descriptor was especially elegant, three spare words that summed up what American Protestants glimpsed in society’s mirror.

To intellectual historians examining localities of knowledge, Stowe’s work stands out. For her, region and religion are one. In Oldtown Folks, she focused on the “intense clearness” of New England theology, with its “sharp-cut crystalline edges and needles of thought,” which “has had in a peculiar degree the power of lacerating the nerves of the soul, and producing strange states of morbid horror and repulsion.” Peering out over her narrator’s shoulder at “all the quiddities and oddities of our Sunday congregation,” Stowe marveled at how the pews of John Eliot’s old mission church expanded to include Arminians, Calvinists, skeptics, African royalty, formerly enslaved persons, village slackers, wayward orphans, stern deacons, and Native American women. “Suffice it to say, that we all grew in those days like the apple-trees in our back lot,” she wrote. “Every man had his own quirks and twists, and threw himself out freely in the line of his own individuality; and so a rather jerky, curious, original set of us there was.” This panorama is among Stowe’s richest. She understood that diversity peopled the American religious tradition. And she recognized the merit of explaining that history to the rest of the world.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Oldtown Folks was a well-embroidered set of character sketches that she modeled from husband Calvin’s earliest reminiscences of Natick, Massachusetts. At the heart of the story are three orphans who experience variant forms of Christian nurture, a sort of “real-world” test run of Horace Bushnell’s philosophy. Like her crab-apple trees, the plot twists and bends on the growing children’s spiritual choices. They must throw off Calvinist doctrine in favor of new forms of Christian citizenship. It is the only way they can move ahead in the world. The three orphans confront the “tyranny of the hard New England logic” as they deal with parental loss, school, work, and (often ill-advised) romantic attachments.

Childe Hassam, “Writing” (1905-1909)

Nearly every archetype in New England religion and its “code of spiritual etiquette” plots out the pages of Oldtown Folks, but Sunny Memories also poke through. Recalling her time in Geneva, Stowe injects a serious intellectual defense of Calvinism, one that fans of The Minister’s Wooing might not expect. A shrewd Calvinist grandmother doubles for Cotton Mather, rifling through a treasured copy of Magnalia Christi Americana to press her arguments with a fairly Arminian husband across the hearth. (She wins, a lot). Stowe envisions a Christian America where the worst theological rifts have healed, and the dialogue regenerates for the sake of improving the New England character. It is a fine synthesis of Old and New World Christianity—a real marriage of the minds—right up until industrial progress hits the town. New archetypes roll in, symbolizing the latest cultural trends reshaping American faith. Evangelical revivals rattle through Oldtown, swallowing up a veteran deacon in the process. He regrets his fervor, when:

“the money for the mortgage is due, and the avails for the little country store are small; and somehow a great family of boys and girls eat up and wear out; and the love of Christ seems a great way off, and the trouble about the mortgage very close at hand; and so the deacon is cross, and the world has its ready sneer for the poor man. ‘He can talk about the love of Christ, but he’s a terrible screw at a bargain,’ they say. Ah, brother, have mercy! the world screws us, and then we are tempted to screw the world.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe is best to read in instant replay. Her ho-hum narrative lulls us in close as she pulls back, then snaps forward from her gut with the bloody kinesis of a sweet uppercut: “The world screws us, and then we are tempted to screw the world.” Bigger than a charming small-town fable, the novel feels well-suited to the faithful (and faithless) populations of 1865 America. “It is more to me than a story,” Stowe explained of her drive to write Oldtown Folks. “It is my résumé of the whole spirit and body of New England, a country that is now exerting such an influence on the civilized world that to know it truly becomes an object.” In treating the spiritual wounds of the Civil War, a worldly Stowe had applied what she gleaned from Europe and patched it up with New England medicine. She returned to the Continent again and again, harvesting ideas that came to life in The Minister’s Wooing (1859) and Agnes of Sorrento (1862). Now a seasoned traveler, the American pilgrim felt ready to pierce the medieval mind, at least on paper. She had gained some spiritual equilibrium in weighing Christianity and civilization, but she did not rest. Harriet Beecher Stowe singed the lines of Agnes with a question born of both the feudal past and her own well-copyrighted version of American life. “Is there a Holy Church? Where is it?” she wrote. “Would there were one!”

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Sarah, thank you for this absolutely beautiful essay. In reading Stowe’s reflections on her experience of Mass, I am reminded of the sonnet cycle that Stowe’s fellow New-Englander Longfellow wrote about translating Dante. That sonnet sequence was included in the American Literature survey text used at my high school, and those poems introduced me to the idea that there might be something more to Catholic piety than “rote superstition.” (It was a further elaboration, I guess, of an inkling that had first dawned upon me as a youngster contemplating the lyrics to a song from Mary Poppins — “All around the cathedral, the saints and apostles look down as she sells her wares…”)

There are many, many factors that would explain how/why Longfellow and Stowe had such different responses to being immersed in the liturgy, or at least the liturgical space, of “Old World Christianity.” In one sense they stood on the common ground of region and country and calling or career as the leading authors of their time, but I suppose that Longfellow was more at ease in that role than Stowe was.

For those who aren’t familiar with the Longfellow sonnets, here is a link:

“Divina Commedia”

They’re beyond lovely.

Thanks, LD. What an exquisite meditation Longfellow achieves! “And many are amazed and many doubt.” Connecting to Andy Seal’s framing of novels as primary sources for intellectual history, I wonder how you all use poetry like this in the classroom? We certainly deploy it in public history to explain the 19th century and the historical consciousness of “the popular heart,” which can feel weighted down by so much press and print. Longfellow always has such a soar and gallop (sorry) to his verse; it’s easy to see why he shaped a few generations’ worth of early American history knowledge. I always like to imagine that Bowdoin Class of ’25 in early bloom: Longfellow and Hawthorne, plunging through the past together.