Editor's Note

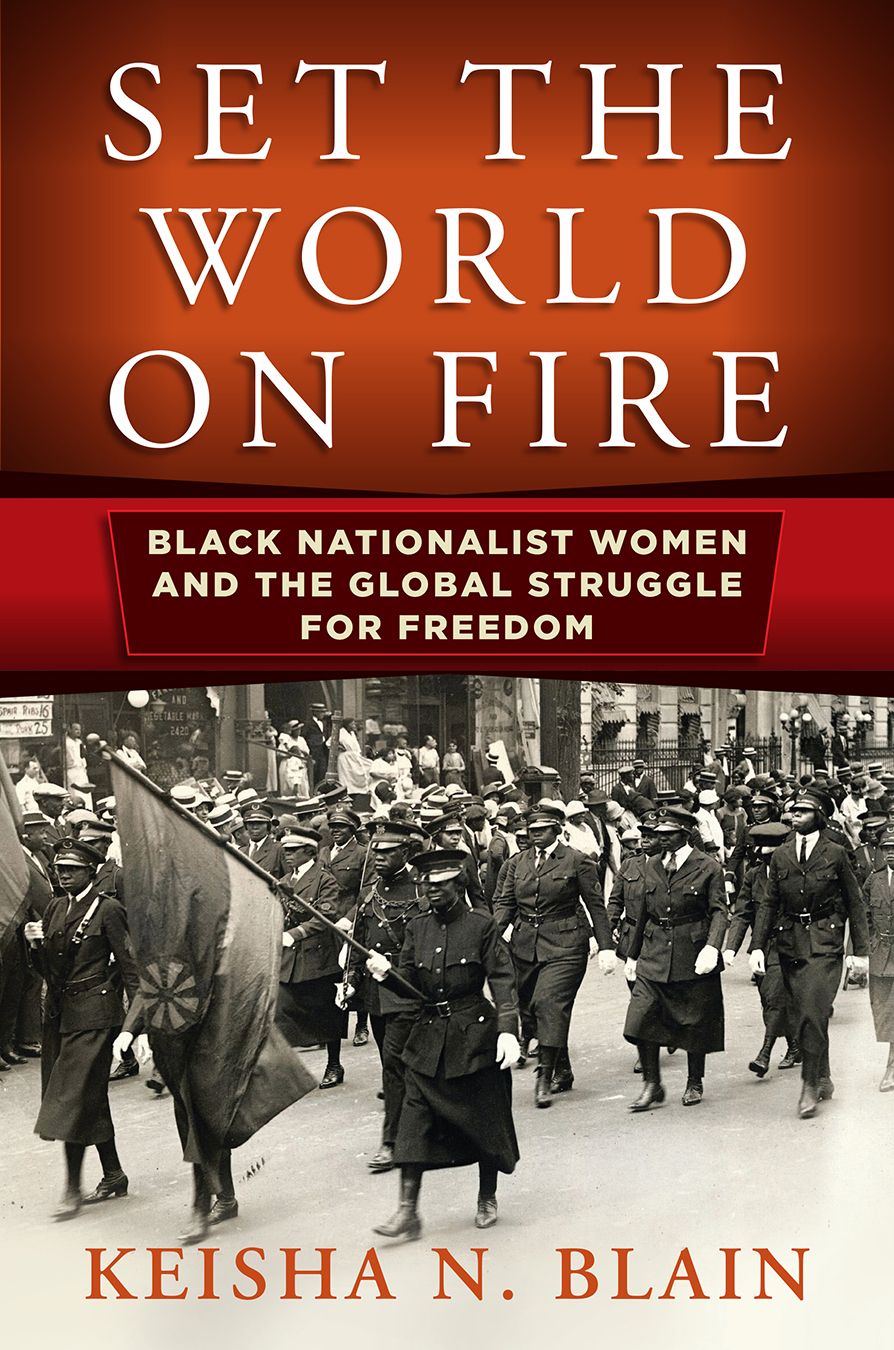

This next contribution to our salon on Dr. Keisha Blain’s book Set the World on Fire comes from guest blogger Tiana Wilson.

Tiana Wilson is a second year PhD student in the History department at the University of Texas at Austin. She is pursuing a Women and Gender Studies portfolio. Tiana researches the Black Freedom Struggle from an internationalist approach by exploring the lives of African American women expatriates of the Black Power era. At UT, Tiana serves as a research fellow for the Center of Race and Democracy and is a graduate editor of the Undergraduate Journal of Black Business History. In addition, Tiana regularly engages in public history by contributing to notevenpast.org and ClioVis.org.

Professor Keisha Blain’s Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom challenges scholarship that posits black nationalism as declining after Garvey’s deportation. Instead, Blain decenters Harlem as the key location of black nationalist ideas and foregrounds black southern women’s activism and ideologies in the movements for global black liberation. By approaching black internationalism at a local level, Blain underscores how women “on the margins” struggled to make their way to the center (21-22). Furthermore, she is most concerned with how impoverished women sought to achieve their political goals and why they chose certain strategies and tactics.

By tapping into white supremacist archives, Blain demonstrates how black women made unusual alliances to accomplish their goals of emigration. For example, during the mid- 1930s, Mittie Maud Lena Gordon, founder of the Peace Movement of Ethiopia (PME), started a massive letter campaign, in which she targeted white supremacist Earnest Sevier Cox for financial support in her emigration efforts. By using Cox’s papers housed at Duke University, Blain reads against the grain to unveil Gordon’s ideological reasoning for this odd alliance. Within Gordon’s letters, it appears she praises Cox as benevolent through her references of him as a “good” and “humble” supporter. However, Blain highlights Gordon’s tone in the letters as a “conscious attempt to perform an act of submission and deference to white male control” (92). Blain makes the point to emphasize Gordon’s tone as a strategic method to underscore the extreme measures black nationalist women took to acquire the finances for their internationalist and emigration efforts.

As Blain makes clear, Gordon deliberately worked with different groups, including Japanese activists that landed the PME on the FBI’s radar. Utilizing FBI records, Blain demonstrates how black women protected their organizations from white surveillance. After Gordon expressed pro-Japanese sentiments, FBI officials sent informants to PME meetings in Chicago and interrogated suspected members in the South. Blain uses a 1941 FBI interview of PME’s member Joella Johnson to emphasize how she carefully crafted her responses. Blain argues that Johnson’s attempt to “downplay her intelligence, interest in the organization, and knowledge of its leaders,” in turn affirms her close affiliation with PME (80). Furthering this claim, Blain makes the case that Johnson was not oblivious to the possible consequence of incarceration if she admitted her political affiliations. Johnson’s response to the FBI officials serves as an example of how working-class black women protected and believed in their organization’s ideas.

Set the World on Fire makes a significant contribution to scholarship on black internationalism. Blain’s noteworthy methodology of drawing on unexpected sources such as white supremacist archives to uncover working-class black women’s efforts to emigrate, is useful for other scholars to follow. She also centers the voices of previously unknown figures and events, making this book valuable for undergraduate seminar courses and more broadly, anyone interested in the histories of black liberation.

0