In the last post in this history of capitalism series, I wrote about the way commodity histories (like Cod: A Biography of a Fish that Changed the World) illuminate some of the influences—intellectual and geopolitical—that shaped the emergence of the new history of capitalism. One of those influences or factors has to do with a broader argument that I’ve been trying to make throughout this series: that the new history of capitalism should not be understood as rooted in or a response to the financial crisis of 2007-2008. Certainly the crisis drew attention to the field at a critical moment in its development, but I think it is a mistake to frame the crisis as a “coming-of-age” moment for the field or as in any important way setting its research agenda or providing its recurrent concerns and underlying motivation. When Jonathan Levy writes in “Capital as Process and the History of Capitalism” (2017) that “the new history of capitalism arrived in U.S. historiography in the wake of the politicization of American economic life during the Great Recession,” I think he is invoking a common but basically inaccurate self-mythologization of the field’s history.

In the last post in this history of capitalism series, I wrote about the way commodity histories (like Cod: A Biography of a Fish that Changed the World) illuminate some of the influences—intellectual and geopolitical—that shaped the emergence of the new history of capitalism. One of those influences or factors has to do with a broader argument that I’ve been trying to make throughout this series: that the new history of capitalism should not be understood as rooted in or a response to the financial crisis of 2007-2008. Certainly the crisis drew attention to the field at a critical moment in its development, but I think it is a mistake to frame the crisis as a “coming-of-age” moment for the field or as in any important way setting its research agenda or providing its recurrent concerns and underlying motivation. When Jonathan Levy writes in “Capital as Process and the History of Capitalism” (2017) that “the new history of capitalism arrived in U.S. historiography in the wake of the politicization of American economic life during the Great Recession,” I think he is invoking a common but basically inaccurate self-mythologization of the field’s history.

Instead, I think it is more correct to trace the new history of capitalism back to the late 90s/early 2000s, and specifically to the conversations about globalization and—to a much lesser degree—to the dot-com bubble. Not only does this map on to the careers of the principal figures in the new history of capitalism more naturally, but it also (as I tried to explain in my last post) helps explain why the field has focused so much on commodification and the flow of commodities.[1] Critical responses to the acolytes of globalization could take many forms—from protest against the power of transnational institutions like the WTO to a melancholic celebration of the lost world of Fordism—but one fairly common and fairly potent expression was a desire to unravel global supply chains and take back some control over how the products you consumed were sourced and manufactured. Whether through fair trade or anti-sweatshop activism, buy local campaigns or other forms of ethical consumption, a mounting consciousness and conscientiousness about the extraordinarily complex nature of how various raw substances become commodities would be basic to many young people’s political awakening and to their first attempts to grasp a more sophisticated understanding of how the world worked.

This political awakening overlapped with certain intellectual trends that were similarly pervasive at this time, themes or tropes that help us understand why “capitalism” looks the way it does in the history of capitalism—why it is conceptualized the way it is. For this argument, I want to jump off from the Levy piece cited above, which (despite my quibble with its dating of the field’s “arrival”) is absolutely brilliant, one of the most stimulating theorizations of the field’s foundations and suppositions yet written.

Levy offers nothing less than a redefinition of the nature of capital. It is important, he argues, not merely to craft a rigorous definition of capitalism in order to anchor the field, but to settle on—or at least have a vigorous debate about—a clear and useful definition of capital itself. After all, he notes, “It would seem impossible to define capitalism without first attending to its root, ‘capital.’ The centrality of capital in modern economic life must be the most compelling reason to invoke capitalism as a category of analysis. Otherwise, why not speak of the economy, enterprise, the market, the commodity form, or some other category instead” (485). (Good question!)

Levy’s definition has a few different components, which I will italicize in the following sentences. Capital, he says, “is a particular kind of pecuniary process of valuation, associated with investment, in which capital may (or may not) become a factor of production” (485). Later, he adds a few further elements: “Capital is legal property assigned a pecuniary value in expectation of a likely future pecuniary income” (487). In other words, capital is simply the cause of a revenue stream, with the stream’s ultimate source located somewhere in the future, flowing backwards into the present. The reason something is capital is that it allows the legal owner to leverage the terms of its future existence to generate pecuniary revenue in the present.

Levy derives this definition from two principal sources—Keynes and Veblen. (Veblen is the reason Levy favors the term “pecuniary,” meaning taking the form of money.) But he also derives it in opposition to other traditional but still powerful definitions of capital that emphasize either its rootedness in past actions (a conventional definition of capital is the accumulation of past savings) or its material embodiment in productive property—in, as the Cambridge History of Capitalism has it, “buildings and equipment, or in improvements to land, or in people with special knowledge” (485).

However, while Levy’s definition is explicitly in conversation with longstanding debates about the nature of capital and owes its fundamental insights to two of the greatest economists of the first half of the twentieth century, I would like to argue that it is still most influenced by—or minimally that it is most similar to—late twentieth century intellectual currents.

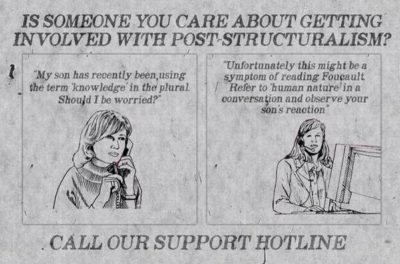

I have tried to make a similar argument a number of ways now, but I don’t think any version of it has proved very convincing. My underlying argument has been that the new history of capitalism has an important intellectual debt to poststructuralism, and particularly to poststructural theories of language that were taken up in history and the social sciences as “the linguistic turn.” But “poststructuralism” is, particularly for many historians, a nebulous term: the set of associations it carries and even the particular thinkers or texts connected to it may differ widely from one person to another. To be more precise, one’s exposure to the term (and thus one’s understanding of what is included under it) likely depends largely on the nature and timing of one’s graduate (and maybe undergraduate) education.

But that in itself is, in some ways, the point. The new history of capitalism is, by and large, a field that has been defined by historians’ first books—by the works that were most shaped by graduate school, and by graduate school at a particular time—the late 90s and early to mid-2000s. And part of that graduate education—usually in the form of cultural history—was an exposure to poststructural theories of language.

It is possible that phrasing my argument simply as “the insights of cultural history were essential to the development of the new history of capitalism” will seem rather unremarkable, but that is why I prefer to emphasize the significance not just of cultural history or even the “linguistic turn” but of poststructuralism as an influence on the new history of capitalism. It was not just a greater sensitivity to “culture” or to the ways people make and encode meaning, but some specific ideas about how language functions or what language is that became part of the logic of the new history of capitalism.

At the center of this influence is the concept of the perpetual deferral of meaning within language: that language (especially in writing) is never wholly identical with itself, that a word never includes the totality of its meaning within itself, that the completion of that meaning is always deferred, both in the sense of postponed but also in a deeper sense of never quite arriving. In the Derridean lexicon, this deferral is figured in the concept of différance. Here is how the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy expresses it:

The meaning of a text is constantly subject to the whims of the future, but when that so-called future is itself ‘present’ (if we try and circumscribe the future by reference to a specific date or event) its meaning is equally not realised, but subject to yet another future that can also never be present. The key to a text is never even present to the author themselves, for the written always defers its meaning.

My argument is that this basic conception of the (written) text resembles in important ways what Levy defines as capitalization: if we replace “meaning” with “(pecuniary) value” and “text” with “legal property” or “economic asset,” do we not get something very close to his definition? Textualization and capitalization are, in form, quite similar processes.

In both, the future has a kind of magnetic power over the present: it orients and also pulls, draws, or strains the present toward itself. Here is another passage from Levy:

to paraphrase and reverse Marx, under capitalism it is not so much the past but the future that weighs on the brains of the living—and, often enough, just like a nightmare. That is perhaps capitalism’s greatest transformation: to order present economic action toward an uncertain future, as opposed to the mere replication of the economic past (the dominant temporal order of precapitalist economic life). Irving Fisher perhaps put it most succinctly. With respect to capital, “when values are considered, the causal relation is not from present to the future, but from future to present.” It is this orientation toward an uncertain future that helps account for capitalism’s propulsive dynamism and periodic fragility. (500)

Deferral, then. A starting point for thinking about the intellectual debts that the new history of capitalism might owe to poststructural theories of language. I’ve only crudely drawn this parallelism, but I hope it is at least suggestive. And to it I would add one more link, for which I would redirect you to the first of Levy’s definitions of capital I cited above: “a particular kind of pecuniary process of valuation, associated with investment, in which capital may (or may not) become a factor of production” (485).

One of the most interesting but relatively understated elements of Levy’s argument is his handling of what he critiques as the “materialist capital concept,” the definition of capital (as explained above) as physically embodied factors of production. Levy identifies this definition with an invidious division of economic activity into two metaphysically unequal kinds—it “treats monetary and financial dynamics as extrinsic to both capital and the ‘real economy’ in general” (486). Levy is suspicious of this distinction, and he argues that recent work in the new history of capitalism has for the most part insisted on transcending or ignoring it. “In recent years, many historians (and also economists) have almost instinctively broken away from the materialist capital concept… They have revived interest in issues of money, credit, and finance, phenomena no less and no more economically ‘real’ than physical production” (488).

It is possible that I am forcing a connection to poststructuralism here, but I don’t think so. Levy’s refusal of the materialist capital concept is also a refusal of what Derrida called a “metaphysics of presence” in which presence is philosophically privileged over non-presence. To quote the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy again: “Western philosophy has consistently privileged that which is, or that which appears, and has forgotten to pay any attention to the condition for that appearance. In other words, presence itself is privileged, rather than that which allows presence to be possible at all.” This seems to me to be very close to the way Levy articulates his reasons for abandoning the materialist capital concept: physically embodied factors of production are privileged over the monetary and financial operations which make their construction, maintenance, etc. possible, but there is no logically consistent reason why that should be. The distinction between the “real” economy and mere financial activity is a hollow or illusory one.

That may be a hard argument fully to absorb, in part because I think many historians instinctively sympathize with a kind of residual producerism: between a banker and a dockworker, we side with the dockworker as the economically productive member of society. Levy, however, argues that this kind of thinking is caused by an incorrect conception of capital and a confusion of capital with wealth. That argument is itself rather involved, so I won’t explore it further at present. (Perhaps later on, in a comment.) The more important thing, I feel, is the way Levy’s thinking fits in with a Derrida-like refusal of the metaphysics of presence and the way this reflects a broader tendency within the field to move away from a crude materialism that was relatively naïve about the significance of financial and monetary phenomena.

In sum, I find that the interest in those financial and monetary phenomena among historians of capitalism was sparked and shaped by an exposure to poststructural theories of language and the intellectual room they opened up to taking seriously abstract or non-physically present factors in economic activity.[2] It may not have been a direct or wholly conscious influence, but I think the connection is there and is substantial enough to be noted and, possibly, further explored.

Notes

[1] Cf. Levy 2017, “If there has been one shared impulse [among the new historians of capitalism], it is probably the study of commodification. Follow the commodity wherever it may lead, across thresholds of space, time, and the ever-expanding boundaries of the market” (483).

[2] We can best see this intellectual convergence in the growing body of scholarship on “the poetics of finance.” See Leigh Claire La Berge, Scandals and Abstractions: Financial Fiction of the Long 1980s (OUP, 2014); Alison Shonkwiler, The Financial Imaginary: Economic Mystification and the Limits of Realist Fiction (University of Minnesota Press, 2017); La Berge and Shonkwiler, Reading Capitalist Realism (University of Iowa Press, 2014); Annie McClanahan, Dead Pledges: Debt, Crisis, and Twenty-First-Century Culture (Stanford University Press, 2018); and Arne de Boever, Finance Fictions: Realism and Psychosis in a Time of Economic Crisis (Fordham University Press, 2018).

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for your very interesting post. Let’s assume that you’re right about the influences on historians of capitalism, especially if “poststructuralism” remains, as you write, a conveniently “nebulous term.” There may be something fascinating about this:

Levy does not mention poststructuralism at all but instead claims that Thorstein Veblen’s recognition of both the contingency of the “forward-looking capital process” and the non-existence of “hidden metaphysical essences” may “safely be labeled pragmatist.” Regarding J.M. Keynes, Levy cites the work of John B. Davis, who compares Keynes to the later Wittgenstein on “language-games,” so that “the numerical representations involved in establishing an investment’s value have a meaning for investors in terms of the social practice–or convention–that links them to one another.”

I wonder how we get from pragmatism or something like “language-games” to Derrida. I wonder if I can put forth a possibly unfair idea. Levy writes of the revised definition of capital, “this is not to say that capital cannot or should not be abstracted from time for useful purposes of quantitative measurement or mathematical modeling.” He claims that such measurement and modeling “will continue to illuminate the historical record.” Likewise, Davis distinguishes Keynes from Wittgenstein because economics has “the sort of determinacy” that is not possible in other forms of social interaction, as seen in the “quantitative categories economics typically applies.”

I wonder if the move to “poststructuralism” is to render economics far less determinable and almost completely “animal spirits,” so that–to put it bluntly–there’s less math and more “poetics?” Of course, that might be the right move, but it’s hardly obvious, and a non-historian might be forgiven for wondering if it’s a little opportunistic, right?

Hi William,

I think you’re being a little too coy here, because I’m not sure whether the point of your comment is directed at Levy or at me, or perhaps at historians generally. Can you clarify?

(I should clarify–quickly. I did not mean methodologically “opportunistic” on your part, but, rather, a sort of general disciplinary opportunism on the part of the historians of whom you write. I’m sorry about my inattentiveness.)

Hi William,

That’s totally all right! I was just confused as to whether I should be speaking on my own behalf or trying to consider your questions from the point of view of Levy’s essay.

I think there may be some opportunism in the sense that historians of capitalism are using a more general interest in topics like finance and its role in daily economic life to draw more attention to their work than it might otherwise get, but I’m not sure that the typically pejorative connotations of “opportunism” are wholly fair.

For one thing, I feel that there is a more general eagerness among historians to bring their expertise to the public square: historians of capitalism who comment on, say, the slave plantation origins of managerial methods are doing so because they genuinely believe they are offering the public an important insight that would be unavailable otherwise. No one else is covering that beat, so to speak. So, if by “opportunism” you mean something like “grabbing onto an opportunity for personal advancement,” I feel like historians of capitalism are no more guilty than lots of other scholars who are pursuing a larger public profile.

I guess the other sense of opportunism might be that historians of capitalism are using one label for their work while doing something else quite different (your previous comment makes me think this might be what you mean). To me, that line of critique is just an example of disciplinary possessiveness and boundary policing. “Capitalism” doesn’t belong to the economists.

Thank you for your response to my comment. Let me retract my use of the word “opportunism,” which is at best premature. Further, I have no interest in “disciplinary possessiveness and boundary policing,” nor do I wish to restrict the role of historians in “the public square.” My concern here is about methodology. I can express it in a question: How and why do we move from Levy’s appeals to Veblen and Wittgenstein to (what I take to be the historians of capitalism’s appeals to) Derrida and poststructuralism?

Obviously, the answer might be 1) Veblen and Wittgenstein are equivalent to Derrida and poststructuralism for them or 2) they believe they have sufficient warrant to move from Veblen and Wittgenstein to Derrida. At present, I am not sure.

If I haven’t made it clear, I learn a great deal from your posts, especially your close readings of texts, and remain grateful for them.

This is a really interesting post.

Levy’s take risks obscuring two things to me: one would be the longer history of forward-looking investment. I am no economic historian and still less an economist, but Levy’s definition it seems to me ends up giving a lot of credence to the skeptics of the “new” history of capitalism, from Naomi Lamoreaux (confession: my 19th century US grad survey professor when she was at UCLA) to Jacob Soll (confession: sometime interlocutor and blurber of my book). Not surprisingly, a good deal of the skepticism comes from historians who have worked on the early 19th century or before, and so they don’t take modernity’s self-constituting claim to novelty at face value. I suspect this dilemma or mistranslation between early modernists and modernists could be applied to intellectual history, too…

Relatedly, the second thing Levy’s time frame risks obscuring, I think, is the intellectual history of political economy, and here I am thinking of Istvant Hont, Michael Sonenscher, Bernard Semmel, Sophus Reinart, Mary Poovey, even Pocock and Joyce Appleby’s early work, among others, which all taken as a whole is partly itself attached to the linguistic turn and poststructuralism (one could even argue the Scottish Enlightenment begat some of the constructivist analysis of law, language, and symbolic authority one usually associates with some of poststructuralism or antifoundationalism in the first place, and you can follow that rabbit hole back to the transmission of civic humanism, etc.). Not for nothing are Foucault’s concepts of governmentally and biopolitics rooted in an extensive reading of the intellectual history of political economy. The genealogical critique of liberalism, whether from Foucault or Arendt or others in the 20th century, I would think, has a lot to do with the intellectual prehistory of the new history of capitalism.

Intellectual history should be a big part of economic history, that seems to the import of this post which is a point well taken. Geoff Mann’s book In the Long Run We Are All Dead, an amazingly good and important book, speaks to some of the holes in these conversations as I have read them, admittedly amateurishly and in passing.

Thanks, Matt!

I should take responsibility for any confusions about Levy’s argument here: your two objections may be my fault rather than his.

First, it’s important to separate Levy’s (re-)definition of “capital” from a definition of capitalism. Capitalism is not just the presence of capital, but rather a society in which capital generation becomes a dominant imperative. Or as Levy says, “Capitalism is an appropriate designation when the capital process has become habitual, sufficiently dominating economic life, having appropriated the production and distribution of wealth towards its pecuniary ends” (487). I don’t think I’m wrong to interpret Levy as saying that capital was present long before capitalism. That seems to me to answer your first point, in part because it allows for a robust discussion of how we might come to some agreement about criteria for where this tipping point might be. I think those criteria would be a mix of quantitative and qualitative markers, but certainly it would be possible to have a productive conversation about what those markers might be.

Your second point, I think, is fair in the sense that Levy’s essay does not engage much with the body of literature you mention. But I’m not sure why his definition of capital would be incompatible with that literature. Levy’s whole point, it seems to me, is to move the conversation away from naively materialist conceptions of what capital is and how it functions in society, and that certainly creates an opening for contributions from the history of ideas. If capital is “legal property assigned a pecuniary value in expectation of a likely future pecuniary income,” then the history of ideas and the intellectual history of political economy would have much to contribute regarding property, value, and the future, just to start with. To me, Levy’s essay is a very promising opportunity for a larger role for intellectual historians in the history of capitalism.