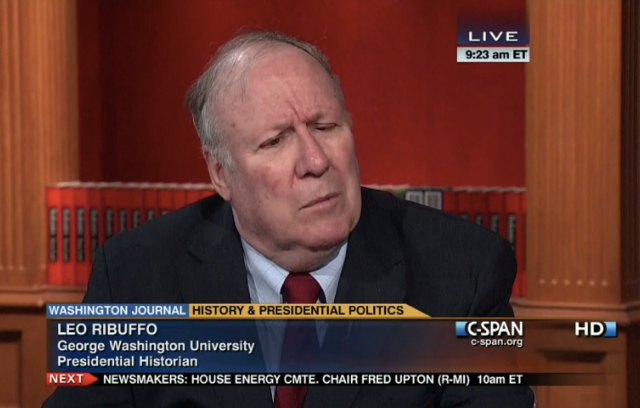

While visiting family in Washington, D.C. over the Thanksgiving holiday, I met my good friend and former dissertation advisor Leo Ribuffo for drinks at an Irish pub. This was our tradition: any time I was in town, we would meet up at a local bar and talk for hours over pints of Guinness and drams (whiskey for me, cognac for Leo).

There was a definite pattern to the topics of conversation at these semi-annual meet-ups. We would begin by discussing the mundane. I say mundane, but Leo always had a way of making even these conversations consequential. We would talk about our students, never in a mean-spirited sort of way, but rather out of genuine curiosity. What did differences in patterns of student behavior across generations mean? Did these differences really add up to anything of significance? For Leo, not much. You see, in the face of an over-excited, gee-wiz punditry that acts as if every recent occurrence is a novelty, he believed it is our singular task as historians to convey the longue durée. Which is why he thought generational analysis was hogwash. As he grumpily barked at me when I was a graduate student arguing that people’s attitudes in the 1950s were uniquely shaped by the Cold War: “Those people had not forgotten the 1930s. It wasn’t that long ago for them!”

There was a definite pattern to the topics of conversation at these semi-annual meet-ups. We would begin by discussing the mundane. I say mundane, but Leo always had a way of making even these conversations consequential. We would talk about our students, never in a mean-spirited sort of way, but rather out of genuine curiosity. What did differences in patterns of student behavior across generations mean? Did these differences really add up to anything of significance? For Leo, not much. You see, in the face of an over-excited, gee-wiz punditry that acts as if every recent occurrence is a novelty, he believed it is our singular task as historians to convey the longue durée. Which is why he thought generational analysis was hogwash. As he grumpily barked at me when I was a graduate student arguing that people’s attitudes in the 1950s were uniquely shaped by the Cold War: “Those people had not forgotten the 1930s. It wasn’t that long ago for them!”

Our booze-soaked conversations eventually always found their way to topics of real substance: politics, history, philosophy, religion—“pointy-headed intellectual stuff” in his words. At our most recent get-together I was so focused on the discussion about Trump and how he ranks against other presidents (not nearly as bad since, unlike many others, he has yet to launch a war that kills millions), and so enjoying our deep dive into Niebuhr, Marx, William James, Cotton Mather (longue durée, natch) that I would not allow myself to interrupt the conversation to use the bathroom even though by that point I had had several pints. Too much information? Nah, this puts my emotions in material form. I so cherished the uninterrupted banter that, by the time we departed the bar, my bladder was on the verge of exploding. Given that Leo died less than a week after our final discourse, I have no regrets.

I first met Leo in January 2002, when I walked into his research seminar on the 1960s. As a budding Marxist who came of intellectual age immersed in Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky, I didn’t think I had anything to learn from a cranky Niebuhrian, William Jamesian, neo-isolationist, unreconstructed McGovernite—especially since I wasn’t equipped at that time to even make sense of these confusing and dare I now say contradictory labels that Leo had given himself. Was I wrong! Leo quickly became my best teacher, and remained so to the end. Whenever I think I have something figured out, I tell myself, yes, but, what does Leo think? We as historians would all do well to ask: What would Leo have thought?

Luckily for us, the editors at the American Historical Review were perceptive enough to ask Leo for his thoughts about Alan Brinkley’s 1994 article, “The Problem of American Conservatism.” Brinkley declared that American historians needed to study conservatives with the same degree of attention that they had given to liberals and lefties. In his response—“Why Is There So Much Conservatism in the United States and Why Do So Few Historians Know Anything About It?”—Leo described Brinkley’s essay as a “certification narrative.” A don of the profession had descended from his Olympian heights to inform us plebs that our work mattered! If you haven’t read that especially Ribuffoesque essay, and if you enjoy the spectacle of historians who bring knives to historiographical battles, do yourself a favor: read it straight away.

Leo was famous for his withering historiographical “interventions” and “interrogations” (he never tired of ridiculing academics for appropriating basic words to make prosaic points sound fancy: he said “interrogation” was something French cops did to bad guys, not something nerds did to texts). I always implored my fellow historians to attend one of Leo’s rousing, hilarious conference presentations. After one such presentation at the 2010 OAH convention about “how historians should study the right now that studying the right is trendy,”he was followed on the panel by Michael Kazin, who declared that following Leo was like trying to follow Jon Stewart. In that paper, Leo once again admonished us for not going back further in time. He declared that his most important suggestion to those who wished to study the history of American conservatism was to “pay more attention to events that occurred before the 1950s—even long before.”

There is simply no other important movement or worldview that historians study in such a truncated fashion. Students of liberalism go back through the New Deal to the so-called Progressive era and sometimes to Andrew Jackson, Thomas Jefferson, and John Locke. Students of radicalism go back through the Popular Front, Debsian socialism, and sometimes to Tom Paine. Conversely, for many participants in the second discovery of the Right [which dates to the aforementioned Brinkley AHR forum], Herbert Hoover, William Appleman Williams’s tragic hero, is a distant and barely recognizable figure.

Leo also suggested, using one of his favorite metaphors, that our efforts to take conservatives seriously as historical subjects demanded that we bury Richard Hofstadter’s chief conceptual contribution to the literature, “the paranoid style in American politics,” “in a deep cavern with nuclear waste.” This was archetypal Ribuffo. He used snark to make what he thought was an obvious point but one that historians ignored over and over again: that calling people to our right (and to our left) “paranoid,” “crazy,” “nut jobs,” “wackos,” was an expedient way to ignore two salient facts. First, that American right-wingers were first and foremost American, in that their history could be explained in very American terms. Second, reserving psychological pejoratives for people outside the safe political center conveniently left out the fact that centrist liberals were not immune from political paranoia. Any sober study of Cold War liberalism proves this point.

Leo will best be remembered as a historian of American conservatism, for good reason. But he also had a deep knowledge of intellectual history, and not just conservative ideas. For instance, he was one of the most informed critics of the pluralist social thinkers of the postwar era—Daniel Bell, Seymour Lipset, Nathan Glazer, Hofstadter—whom he accused of confusing description for prescription when they argued that a pluralist consensus was the defining feature of American history. But whereas most recent critics of these consensus era historians and social scientists treat them merely as mid-century signposts and, often, straw men, Leo actually read their work with care and came away impressed by much of their approach even as he harshly criticized their overriding contention. For instance, Leo liked that these pluralist thinkers, unlike many who came after them, didn’t think American history began in 1945, or 1933, or 1912, or even 1865. As my good friend and fellow Ribuffo student Christopher Hickman reminds me, Leo followed these thinkers in accentuating continuity. Leo, in his own eclectic way, discovered consensus in American history. But his consensus, unlike Hofstadter’s or Schlesinger’s, was much more capacious in that it allowed freaks into the mix.

Leo’s intellectual history chops were on display to me when I took his seminar on “Social Thought in the United States since 1945,” a legendary course among his legions of graduate students. This class, in which we mostly read primary texts from Dwight MacDonald, to C. Wright Mills, to Abraham Maslow, to Barbara Ehrenreich, to Christopher Lasch, to many more (it’s a long list—he expected us to read a lot), was not only far-and-away my favorite class during graduate school, it also gave me the topics for my first two books. (Who am I kidding, Leo explicitly gave me those ideas. In a conversation after one of those classes in 2003, he said, “You should write a dissertation on the education wars of the 1950s.” Then again in 2008, he told me, “You should write a book about the ‘so-called’ culture wars of the 1980s and 1990s.” It always cracked me up that Leo advised me to write a book about a topic that he never failed to qualify as “so-called.”)

Leo also had deep knowledge of political and presidential history. He had been working on a book about the Jimmy Carter presidency for the past 20 or more years. People often asked me why it was taking Leo so long to write what he called “the fucking Carter book,” wondering if perhaps he was stuck. Leo was not stuck. He did write slowly, in part (I think) because of his life-long visual impairment. Also, Leo was a very committed teacher, and had many graduate students, which took up a lot his time. He always read my work carefully, even long after I was officially his student, an act of generosity that I will never forget, even though I tended to curse his name immediately after receiving feedback. After submitting drafts of the first three chapters of my dissertation to him, he returned them with several single-spaced pages of harsh criticism, including the following, unforgettable sentence, which he wrote in response to my long discursive historiographical asides: “You are not Jackson Lears.” By which he meant, I was not yet qualified to write like that. It took me 24 hours (and many beers and bad zombie movies) to calm down and realize that Leo was only being harsh because he knew I would respond well. Leo did tough love better than anyone, because he was tough as nails, and lovable.

But in addition to his eyes and his teaching commitments, Leo’s glacial pace can be attributed to his desire to get the Carter book right. He made annual pilgrimages to the Carter Center in Atlanta to dig into the latest declassified documentation that might help him explain knotty subjects like SALT II or the Camp David Accords. He believed that the 1970s and the Carter presidency were crucial to understanding contemporary America. He was determined to get it right. Word is that he has nine or ten chapters, at upwards 200,000 words, complete. For our sake, I hope the book is published posthumously, even if Leo never finally got it right by the lofty standards he set for himself. In the meantime, for those who want a fuller flavor of Leo’s knowledge of political history, there are dozens and dozens of published essays. I highly recommend his book, Right, Center, Left: Essays in American History, which includes excellent essays on Carter, Henry Ford, Bruce Barton, the American Communist Party, and more.

Lest you think Leo was limited in his scholarly range—I kid—he also knew a lot about the history of American foreign policy. One of my favorite Ribuffo essays was his contribution to the 2004 Ellen Schrecker edited collection, Cold War Triumphalism: The Misuse of History After the Fall of Communism, titled, “Moral Judgment and the Cold War: Reflections on Reinhold Niebuhr, Williams Appleman Williams, and John Lewis Gaddis.” In this essay, Leo “explores an aspect of Cold War intellectual history.” Whereas the Cold War was overflowing with moral judgments, most often of the self-serving type, Leo analyzed three intellectuals who undertook sustained moral reflection about the American role in the Cold War. Leo took sides in this essay, Williams coming out on top, followed closely by Niebuhr, with Gaddis a distant third. But more to the point, this essay demonstrates something Leo stressed time and again across his long career: we must strive for empathy when dealing with people from the past, whether such people are 18thcentury Luddites, American fascists in the 1930s, or pointy-headed intellectuals during the Cold War. In his analysis of Niebuhr, Williams, and Gaddis, empathy meant that, even when he disagreed with their conclusions, he recognized that their conclusions were hard won, and that the problems they grappled with offered no easy solutions. For Leo, as for Niebuhr, Williams, and Gaddis, the world was complex, ironic, tragic. Any effort to sidestep that was intellectually lazy.

I would like to quote at length two passages from this essay, because they perfectly capture Leo as a thinker and writer. The first is the last paragraph in his introduction where he stated his perspective. The second is his description of Niebuhr’s perspective, which, with some secular qualifications, was also Leo’s perspective. These paragraphs pack serious intellectual punch, but are communicated in Leo’s typically clear and unpretentious prose.

My perspective is, broadly speaking, a version of pragmatism. “Facts” and “values” do not dwell in separate spheres but interact, and we should be conscious of that interaction. Moral judgments should be based on the consequences of human actions at least as much on the motives. Actions—or even notions about the right ways to act—are constrained by time, place, and circumstance. Consequences of human actions are often unpredictable and change over time, and these changes typically affect both our conceptualization of facts and our ethical judgments.

…

By the early 1930s Niebuhr had formulated an approach to God, humanity, and society that he called “Christian realism.” According to Niebuhr, bourgeois secular liberals and Protestant social gospelers exaggerated humanity’s capacity for virtue and wisdom. At most, altruistic behavior was possible only in small groups. Because men (as he put it) were inherently sinful, at least in a metaphorical sense, their social movements and governments were always morally tainted. Virtues turned into vices when they were pressed too zealously, and evil means were used to advance relatively noble ends. Nonetheless, men should not sink into cynicism but attempt to achieve ideals that were impossible to attain.

I realize I have described Leo’s work at some length and have yet to mention his signature piece of scholarship, The Old Christian Right: The Protestant Far Right from the Great Depression to the Cold War. Published in 1983, The Old Christian Right won the OAH’s Merle Curti Award for best book in American intellectual history. I have left the best for last.

Last month at S-USIH in Chicago, I had the honor of organizing and chairing a roundtable dedicated to reevaluating The Old Christian Right. Leo was the least sentimental, least nostalgic person on the planet—his will mandated no memorial service upon his death—and yet I could tell Leo was happy with the roundtable. He hated festschrifts, yet I was lucky to give him a great one. Now, thanks to the USIH Blog, which will publish an edited version of the roundtable over the next week, everyone will be able to enjoy it.

The Old Christian Right is a close study of Depression-era native fascists William Dudley Pelley, Gerald B. Winrod, and Gerald L.K. Smith. With this book, to my mind, Leo accomplished at least three things. First, he was arguably one of the only left-leaning historians of his generation (not to mention the preceding “consensus historian” generation) to treat the far right without condescension. Second, Leo’s analysis served as a poignant contrast to a gobsmacked punditry then reporting on the surprising emergence of the “New” Christian Right that had helped propel Reagan to the White House. Third, the book was a methodological meditation grounded in deep knowledge of the psychological theories of extremism that had informed scholars of the “radical right” since before World War II. Our roundtable participants discuss all of these historical and historiographical issues, and more. They also fruitfully ponder the ways in which Leo’s analysis of American fascism in the 1930s resonates in an era when the “f-word” is perpetually on people’s lips again, in ways that Leo objected to.

Let me now briefly introduce the distinguished contributors to this roundtable, all of whom are experts on modern American conservatism. First, Rick Perlstein, a renowned journalist and author of several books that most of us have read, including Nixonland

. Second, Michelle Nickerson, associate professor of history at Loyola University, Chicago and author of Mothers of Conservatism: Women and the Postwar Right. Third, Elizabeth Tandy Shermer, also an associate professor of history at Loyola University, Chicago, and author of Sunbelt Capitalism: Phoenix and the Transformation of American Politics. Last, a response from Leo Ribuffo, the late Society of the Cincinnati George Washington Distinguished Professor of History at George Washington University.

I will conclude by mentioning something most people probably don’t know about Leo Ribuffo: he supervised 30 dissertations in his 40 plus years at GWU, including mine, many of which have gone on to become books. We Leo advisees like to refer to ourselves as Ribuffoites.

In a fitting tribute to his legacy, below is a bibliography of Ribuffo-advised dissertations that became books. Leo will be missed, but not forgotten.

- JoAnn E. Argersinger, Toward a New Deal in Baltimore (University of North Carolina Press, 1988).

- John Maxwell Hamilton, Edgar Snow (Indiana University Press, 1988).

- Thomas A. Kolsky, Jews Against Zionism: The American Council for Judaism, 1942-1948 (Temple University Press, 1990).

- George D. Moffett, III, The Limits of Victory: The Ratification of the Panama Canal Treaties (Cornell University Press, 1985).

- Edward J. Sheehy, The US Navy, the Mediterranean, and the Cold War, 1945-1949 (Greenwood Press, 1992).

- John Ehrman, The Rise of Neoconservatism (Yale University Press, 1995).

- Allida M. Black, Casting Her Own Shadow: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Shaping of Postwar Liberalism (Columbia University Press, 1996).

- David Marley, Pat Robertson: An American Life (Rowman and Littlefield, 2007).

- Andrew Hartman, Education and the Cold War: The Battle for the American School (Palgrave, 2008).

- Victoria Grieve, The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middle Brow Culture (University of Illinois Press, 2009).

- Sarah K. Mergel, Conservative Intellectuals and Richard Nixon (Palgrave 2009).

- Earl Tilford, Air Force Search and Rescue Operations in Southeast Asia 1961-1975 (Center for Air Force History, 1981).

- Christopher Bright, Continental Defense in the Eisenhower Era: Nuclear Antiaircraft Arms and the Cold War (Palgrave, 2010).

- Kristen Gwinn, Emily Greene Balch: The Long Road to Internationalism (University of Illinois Press, 2010).

- Felix Harcourt, Ku Klux Kulture: America and the Klan in the 1920s (University of Chicago Press, 2017).

- Emily Dufton, Grass Roots: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Marijuana in America (Basic Books, 2017).

15 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

What a thoughtful and illuminating tribute. (I found it esp. informative since I never met him or heard him speak and, apart from a couple of old pieces in Dissent, have never read anything he wrote.) The list of the dissertations that became books — the fact that his students wrote about everything from neoconservatism to foreign and military affairs to marijuana — is itself so indicative of the range of his scholarly interests.

Beautiful remembrance Andrew! I’m so glad I attended this panel, Leo really rose to the occasion. I fear the text won’t translate the voice inflection and sardonic humor so clearly as the presentation.

Lovely tribute, Andrew. One part in particular jumped out at me:

“What did differences in patterns of student behavior across generations mean? Did these differences really add up to anything of significance? For Leo, not much. You see, in the face of an over-excited, gee-wiz punditry that acts as if every recent occurrence is a novelty, he believed it is our singular task as historians to convey the longue durée. Which is why he thought generational analysis was hogwash.”

Particularly coming from an older white man, this is really refreshing. Teaching is hard — too often we’re tempted, as teachers, to blame our students for the challenge it will always involve. We could certainly use more of his long-duree clarity.

Andrew, thank you for this. Thank you especially for including his marginal comment, “You are not Jackson Lears.” I laughed out loud at that. And I love the still-frame you chose for this post. I’m assuming that is something close to Leo’s “I’m fixing to tell you all the ways you are wrong” face. I just can’t believe that he was so ebullient and charming and smart and lively at our conference, and then he was gone. It’s really heartbreaking; I can only imagine how deeply grieved all his students and colleagues and longtime friends are, and you have all our sympathy and support. What a character he was, and what a loss is his passing.

Thank you, Andrew. Leo was a prince, and a student, all his life. He never forgot where he came from, and he never gave up on his destination–which would be redemption.

damn

Thank you for this elegant tribute, Andrew. I am stunned: Coming up for air in the last sprint of grading, lecturing, and all the rest as the term ends only to learn this sad news. My condolences to you and to all Leo’s many students, friends, and admirers. Count me among the latter: Leo was a good man and exacting scholar, as I learned by getting to know him at S-USIH meetings. He helped me, too, generously agreeing to read an essay draft, and yes, I learned he was a tough and maddening critic. I last saw him in Chicago, with a drink in hand. It was a soft drink, he noted, as he was pacing himself, preparing to meet you, Ray, and perhaps some others. He was positively merry.

Thanks everyone for the kind comments. Though necessary and cathartic, writing this essay was incredibly difficult for me, so I truly appreciate you all reading it.

Andrew, An excellent tribute. Much appreciated.

This is lovely, Andrew. He was a tough cookie, but he was also generous; his work was solid and his skepticism of academic trends, especially in history, was smart and welcome, at least by me. He will be missed.

A fitting tribute to an intellectual giant who sired many acolytes and ideas, which live on as tangible evidence of his contributions to history.

Thank you for evoking the same Leo who was the heart of our graduate community at Yale in the 1970s. Even under these sad circumstances, it iswonderful to note how many students he had mentored and to be reminded of the generosity that marked his entire life.

I can’t say I “knew” Leo Ribuffo, but I did spend a memorable evening with him back around 1997 or so. He was an invited speaker (talking about his Carter research) and the chair of our department was nice enough to note my interest in intellectual history and invited me along to be a part of the small conversational bouquet to have dinner with him after. It went way into the night, and it was quite a joy. He was among the most unpretentious and genuinely curious scholars I’d ever dined with, and the conversation ranged seemingly in every direction. I’ve actually recalled that evening often for no other reason than that it was so enjoyable. He could say all kinds of potentially shocking things (“Social history will never dominate the profession because even people who get paid to say ‘race, class and gender’ over and over get bored saying ‘race, class and gender’ over and over”–or something to that effect) yet somehow you were certain he was coming from a place of genuine concern about the shape and fate of the discipline, and not from any attempt to achieve personal or professional advantage. I think the best small tribute I could offer, after that night and after reading the memories here, is to say I wish I could have known him as well as some of you did.

In case anyone would like to explore some of Leo Ribuffo’s many publications, here is a list.

PUBLICATIONS

BOOKS

The Old Christian Right: The Protestant Far Right from the Great Depression to the Cold War (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1983)

Editor, Contemporary America, special issue of American Quarterly Spring-Summer, 1983

Right Center Left: Essays in American History (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1992)

ARTICLES, CHAPTERS, SELECT REVIEWS, ETC

“‘Pluralism’ and American History,” Dissent, Winter, 1971

“The Plausible and the Wacky,” Nation, Sept. 20, 1971

“The Long Cold War,” Nation, May 20, 1972

“That $1000 Income Grant,” New Republic, Nov. 23, 1972

“Fascists, Nazis, and American Minds: Perceptions and Preconceptions,” American Quarterly, Oct., 1974

“Abusing the Fifties,” Worldview, Nov. 1973; reprinted in Annual Editions in American History, 1975-76

“Watergate and Mugwumps,” Dissent, Winter, 1974

Review of Charles Martin, The Angelo Herndon Case and Southern Justice, in Southern Exposure, Summer, 1977

“Panthers and Bulldogs–Revisited,” (review of John Taft, Mayday at Yale), in Dissent, Fall, 1977

Review of Roy Hoopes, Americans Remember the Home Front and Allan M. Winkler, The Politics of Propaganda, in Worldview, Aug., 1979

“The Energy Crisis and the Analogue of War,” Dissent, Fall, 1979

“B Minus,” (review of Frances FitzGerald, America Revised) in Dissent, Spring, 1980

“Henry Ford and The International Jew,” in American Jewish History, June, 1980

“Liberals and That Old-Time Religion,” Nation, Nov. 29, 1980

“Jesus Christ as Business Statesman: Bruce Barton and the Selling of Corporate Capitalism,” American Quarterly, Summer, 1981

“Monkey Trials, Old and New,” Dissent, Summer, 1981

“United States v. McWilliams: The Roosevelt Administration and the Far Right,” in M. R. Belknap, American Political Trials (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1981)

“Communism and Anti-Communism in America,” Humanities, April, 1984

“Viewing the Fifties from the Eighties,” Reviews in American History, Sept., 1984

“The FDR Tradition: Shadow Boxing,” Dissent, Winter, 1985

“Warren I. Susman as a Teacher of Undergraduates,” in Irene Fizer, ed., In Memory of Warren I. Susman, 1927-1985 (New Brunswick: Rutgers Univ. Press, 1986)

“Jimmy Carter,” in Frank Magill, ed., Great Lives from History: A Biographical Survey (Pasadena: Salem Press, 1987)

“Change and Continuity: The Presidency in Historical Perspective,” The World and I, Jan. 1988

“Nativism and Religious Prejudice,” in Charles Lippy and Peter Williams, ed., Encyclopedia of the American Religious Experience (New York: Scribner’s, 1987)

“Jimmy Carter and the Ironies of American Liberalism,” Gettysburg Review, Autumn 1988

“Jimmy Carter: Beyond the Current Myths,” Magazine of History, Summer-Fall 1989

“God and Jimmy Carter,” in M. L. Bradbury and James B. Gilbert, ed., Transforming Faith: The Sacred and the Secular in Modern American History (Westport, Ct.: Greenwood Press, 1989)

“Is Poland a Soviet Satellite? Gerald Ford, the Sonnenfeldt Doctrine, and the Election of 1976,” Diplomatic History, Summer, 1990

Review of Richard Fried, Nightmare in Red, in Dissent, Summer 1990

“How to Win Votes and Influence Congress,” in Reviews in American History, Sept. 1991

“George Bush,” Richard Nixon,” “Ronald Reagan,” in Eric Foner and John Garraty, ed., The Reader’s Companion to American History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991)

“American Fundamentalism to the 1950s: A New Yorker’s Guide,” in Lawrence Kaplan, ed., Fundamentalism in Comparative Perspective (Amherst: Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 1992)

“God and Contemporary Politics,” Journal of American History, March, 1993

“Jimmy Carter and the ‘Selling of the President,’ 1976-1980,” in Herbert Rosenbaum and Alexej Ugrinsky, ed., Keeping Faith: The Presidency and Domestic Policies of Jimmy Carter (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1993)

Why Is There So Much Conservatism in the United States and Why Do So Few Historians Know Anything About it?” American Historical Review, April 1994

“The Election of 1976,” in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., ed., Running for President (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994)

“God and Man at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Berkeley, Etc.,” Reviews in American History, March 1995

“Religion, Politics, and the Latest Christian Right,” Dissent, Spring 1995

“Dwight Eisenhower,” “Gerald R. Ford, Jr.,” “Barry Goldwater,” “Eugene McCarthy,” ” George McGovern,” in Stanley Kutler, ed., Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War (New York: Scribner’s, 1996)

“Cultural Shouting Matches and the Academic Study of American Religious History,” in Bruce Kuklick and D. G. Hart, ed., Religious Advocacy and American History (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997)

“The Newting of America,” Public Historian, Summer 1997

“From Carter to Clinton: The Latest Crisis of American Liberalism,” American Studies International, June 1997

“Malaise Revisited: Jimmy Carter and the Crisis of Confidence,” in John Patrick Diggins, ed., The Liberal Persuasion (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997)

“There They Go Again: Change and Continuity in American Liberalism,” Reviews in American History, Sept. 1997

“Rural? Radical?” Reviews in American History, Dec. 1997

“Promise Keepers on the Mall.” Dissent, Winter 1998

“Religion and American Foreign Policy,” National Interest, Summer 1998, republished with updating as “Religion in the History of U. S. Foreign Policy,” in Elliott Abrams, ed., The Influence of Faith: Religious Groups and U. S. Foreign Policy (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2001)

“Confessions of an Accidental (or Perhaps Overdetermined) Historian,” in Elizabeth Fox-Genovese and Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn, Reconstructing History (New York: Routledge, 1999)

“The Defender, 1925-1981” in Ronald Lora and William Henry Longton, ed., The American Conservative Press in the Twentieth-Century (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1999)

“Religione e politica esetra americana: Storia di un rapporto complesso,” Novecento [University of Bologna] #2, 2000

“What Is Still Living in ‘Consensus’ History and Pluralist Social Theory?” American Studies International, February 2000

“Jimmy Carter,” “Ronald Reagan,” “Energy Crisis of the 1970s,” in Paul Boyer, ed., The Oxford Companion to American History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001)

“Will the Sixties Never End? Or Perhaps at Least the Thirties? Or Maybe Even the Progressive Era?” Contrarian Thoughts on Change and Continuity in American Political Culture at the Turn of the Millennium,” in Peter J. Kuznick and James Gilbert, ed., Rethinking Cold War Culture (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001)

“What Is Still Living in the Ideas and Example of William Appleman Williams?” Diplomatic History, Spring 2001

“An Empire, Then a Republic?” Diplomatic History, Fall 2001

“Religion” in Alexander DeConde, et al, ed, Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy (2d edition, New York: Charles Scribner’s, 2002)

“One Cheer for this Military Intervention, Two Cheers for Cosmopolitan Isolationism,” Journal of the Historical Society, Spring 2002

“The Discovery and Rediscovery of American Conservatism Broadly Conceived,” OAH Magazine of History, January 2003

“American Fascism,” “Conservatism,” and “Neoconservatism,” in Stanley Kutler, ed., Dictionary of American History (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 2003)

“Conservatism and American Politics,” Journal of the Historical Society, Spring 2003

“1974-1988,” in Stephen J. Whitfield, ed., A Companion to Twentieth-Century America (Boston: Blackwell, 2004)

“Moral Judgments and the Cold War: Reflections on Reinhold Niebuhr, William Appleman Williams, and John Lewis Gaddis,” in Ellen Schrecker, ed., Cold War Triumphalism: The Misuse of History after the Fall of Communism (New York: New Press, 2004)

“The American Catholic Church and Ordered Liberty,” Historically Speaking, September-October 2004

“If We Are All Multiculturalists Now, Then What?” Reviews in American History, December 2004

“Gerald B. Winrod: From Fundamentalist Preacher to ‘Jayhawk Hitler,” in Virgil W. Dean, ed., John Brown to Bob Dole: Movers and Shakers in Kansas History (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2006)

“Family Policy Past as Prologue: Jimmy Carter, the White House Conference on Families, and the Mobilization of the New Christian Right, Review of Policy Research,” March 2006

“George W. Bush, the ‘Faith-Based Presidency,” and the Latest ‘Evangelical Menace,’” Journal of American and Canadian Studies (Japan), # 24 (2006) Chinese translation in Religion and American Society (Shanghai) #4 (2008)

“Religion and American Politics,” Humanities (Tokyo), March 2008

“Ain’t It Awful? You Bet. It Always Is,” forum on the historical profession in the twenty-first century in Donald A. Yerxa, ed., Recent Themes on Historians and the Public (Columbia, University of South Carolina Press, 2009)

“The American Catholic Church and Ordered Liberty,” in Randall J. Stephens, ed., Recent Themes in American Religious History (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2010)

“Twenty Suggestions for Studying the Right Now that Studying the Right is Trendy,” Historically Speaking, January 2011

“Intellectuals versus Scholars,” Chronicle of Higher Education, November 29, 2015

“Jimmy Carter, Congress, and the Supreme Court,” in Scott Kaufman, ed., A Companion to Gerald R. Ford and Jimmy Carter (New York: Wiley Blackwell, 2016)

“George Wallace’s ’68,” Jacobin, Spring 2018

” Leo quickly became my best teacher, and remained so to the end. Whenever I think I have something figured out, I tell myself, yes, but, what does Leo think? We as historians would all do well to ask: What would Leo have thought?” I couldn’t have said it better, and wouldn’t have said it differently.