I’m in the weeds of end-of-the-semester grading at the moment, so this will be a short post.

I’m in the weeds of end-of-the-semester grading at the moment, so this will be a short post.

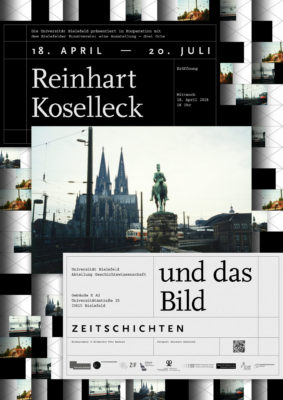

Jonathan Catlin has a fascinating post up on the Journal of the History of Ideas’ JHIBlog about the German historian Reinhart Koselleck (1923–2006). Catlin’s piece is a review of a three-part exhibit entitled “Reinhart Koselleck and Das Bild” (Reinhart Koselleck and the Image), which took place in Bielefeld, Germany, earlier this year. Catlin’s account is fascinating; it was all I could do to put off following the copious links in the post (like I said, grading is my focus at the moment).

Koselleck spent the last years of his life working on issues of memory and iconography, with a particular interest in equestrian statues and war memorials. But he’s best known as the founder of Begriffsgeschichte (conceptual history), an interdisciplinary approach to intellectual and cultural history that focuses on the shifting meanings of key terms. Starting in the late 1960s or early 1970s, Begriffsgeschichte became a hugely influential methodology in Germany. According to Catlin, it’s enjoying a revival today.

I first bumped into Begriffsgeschichte when working on my dissertations in the early 1990s. I consulted a few German-language secondary sources on the idea of totalitarianism and this was one approach that they took. My sense is that sometime in the 1990s, Begriffsgeschichte became more influential on anglophone scholarship. But to this day, there is very little talk of Begriffsgeschichte among U.S. intellectual historians, though I think short pieces by Koselleck often show up on our methodology/historiography syllabi. Unless our search function is failing, this is the first time the word Begriffsgeschichte has appeared on this blog, though Koselleck himself has come up, in posts or comments, fourteen times, always as a theorist or philosopher of history.

Over the last several decades, U.S. intellectual historians have greatly expanded the scope of the things we study. And one of the dimensions of this expansion is that we have been less parochially focused on American materials. Like intellectual historians who focus on other countries, U.S. intellectual historians are starting to think globally.

But I often think we still do not do a good enough job learning from other subspecialties of intellectual history. And most of us are probably better versed in the work of European scholars like Koselleck than we are in the work of those who focus on the intellectual histories of, e.g., China, Japan, India, the Islamic World, Africa, or Latin America.

At any rate, reading Catlin’s post about an influential and brilliant historian, who was interested in many of the sorts of things I’m interested in, but whose voluminous work I know too little brought to mind a problem I was already well aware of. US intellectual historians and intellectual historians who focus on – and come from — other parts of the world too often engage in parallel play, working on similar topics in our own separate sandboxes, when we should be more vigorously exchanging ideas and learning from each other.

0