For months now, I’ve needed to call the dentist to schedule a teeth cleaning. Luckily, sitting down at my desk to do the last of the semester’s grading presented the perfect opportunity. It was good to get that out of the way because my students’ work deserves my undivided attention. I set the music media software on my PC to random play, so to drown out any distractions. “The Other Woman,” by Nina Simone came on. Wow, what a cut! I could (and did) listen to that song over and over. It’s one of my favorites. But something about it bothers me, too.

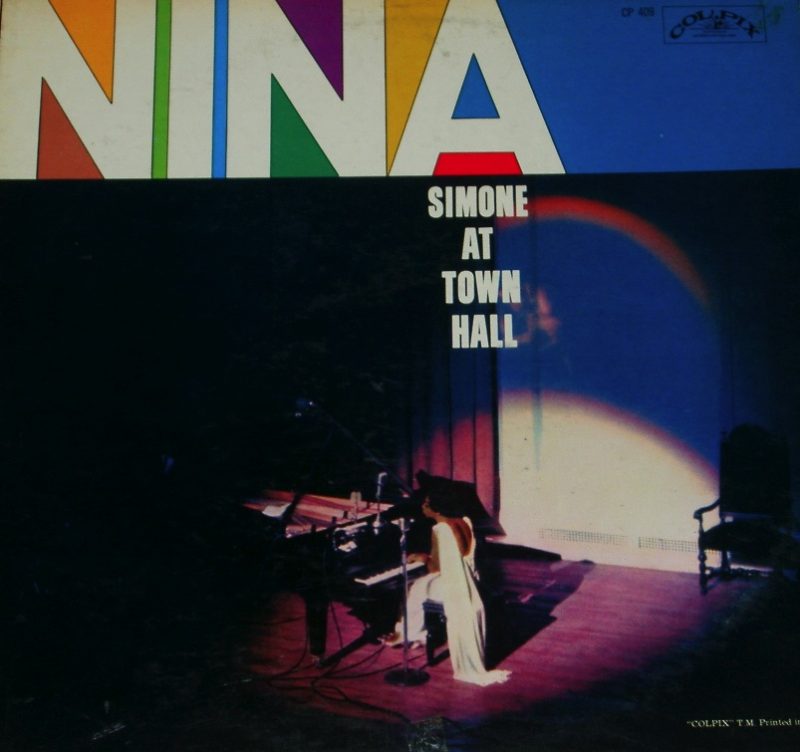

This is the romantic, not the civil rights Simone, the Simone of “My Baby Just Cares for Me,” not of “Mississippi Goddamn.” The 2015 documentary, What Happened, Miss Simone? focuses on the civil rights side and skims over the Simone as interpreter of love songs and the Great American Songbook. That’s understandable. Interest in Simone from the discipline of history, skewing political and social as it usually does, would foreground this aspect, too. But of these two sides to Simone–and there are more than two, actually–one is no more significant than the other. When the explicitly topical material is not made to claim all the attention, the performances can be appreciated in all their dimensions, especially the live ones. This version of “The Other Woman,” recorded live at The Town Hall in Manhattan in 1959, features all of Simone’s distinctive vocal effects: the stair-step climbs up the scale; the pulsing vibrato; the floating melisma on the end of the chorus. Rich musicality and naked emotionalism—this recording puts Nina Simone’s signature traits fully on display.

This is the romantic, not the civil rights Simone, the Simone of “My Baby Just Cares for Me,” not of “Mississippi Goddamn.” The 2015 documentary, What Happened, Miss Simone? focuses on the civil rights side and skims over the Simone as interpreter of love songs and the Great American Songbook. That’s understandable. Interest in Simone from the discipline of history, skewing political and social as it usually does, would foreground this aspect, too. But of these two sides to Simone–and there are more than two, actually–one is no more significant than the other. When the explicitly topical material is not made to claim all the attention, the performances can be appreciated in all their dimensions, especially the live ones. This version of “The Other Woman,” recorded live at The Town Hall in Manhattan in 1959, features all of Simone’s distinctive vocal effects: the stair-step climbs up the scale; the pulsing vibrato; the floating melisma on the end of the chorus. Rich musicality and naked emotionalism—this recording puts Nina Simone’s signature traits fully on display.

What gives me pause about the song is the world it evokes, and that’s a problem with many of the songs of the so-called Great American Songbook, those songs produced by professional songwriters primarily for musical theater and film during the first half of the twentieth century. The message of “The Other Woman” is straightforward enough. For the mistress, carrying on an affair with a married man, the consequences are loneliness and waste. But note those euphemisms, “mistress,” “affair,” and their connotations. The song brings to mind a sort of Mad Men world where the corporate lord has his wife and family contained in some suburb, while in the city, in her own apartment, a sophisticate, a career woman, perhaps, or a failed debutante, awaits him “like a lonesome queen.” She “enchants her clothes with French perfume”; she “keeps fresh cut flowers in each room.” When “her man” arrives, she surrounds him with the abundance, grace, and refinement presumably proper to their station.

I don’t want to say that this world didn’t exist or that these people didn’t exist at all, only that this vision of the world is offered to the listener as if it indicated some sort of normative American ground.

A little internet research complicated the issue very quickly. For one thing, placing “The Other Woman” in the Great American Songbook is problematic. Its writer was Jessie Mae Robinson, born in Call, TX, on the Louisiana border, and raised in Los Angeles. Her birth year makes her more or less contemporary to the second generation of songbook writers, but as an African American woman, she would have had to cross both race and gender lines to be counted within their ranks. Robinson, too, seems to have come late to professional songwriting. She had her biggest successes in the 1950s when the genre of the songbook was going into decline.

Robinson’s other hits are more typical of the postwar period. Her first songs were recorded by some of the lesser known blues and R&B artists. She crossed over when Patti Page had a number one hit in 1951 with “I Went to Your Wedding,” a waltz in cowboy chords. Later in the decade, both Elvis Presley and Wanda Jackson recorded Robinson’s “Let’s Have a Party,” another simple pop tune, this one for the teens. “The Other Woman” sounds like none of these. If it isn’t American Songbook canonical, it’s certainly written that way, in its harmony, its diction, and its narrative space. It’s a stage-set space, where it always seems to be evening, no one seems to work, everyone is dressed up for dinner speaking in a transatlantic accent, exchanging repartee like bored aristocrats.

Again, maybe these people exist, though I’ve never met one, except in songs and stories. And I suspect that many of those who do exist in real life owe that existence to a vision drawn from songs and stories to which they are aspiring–all of them like secret Gatsbys, pretending to a way of being that’s itself a fantasy.

Granted, one of the strengths of many of these American Songbook songs is their encouragement that we not take ourselves so seriously. The current finger-wagging aimed at “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” for its glib illustration of refusing to take no for no may not do a lot to advance the #MeToo movement. “The Other Woman,” in contrast, has real gravitas and contains its own moral accounting. But that accounting only goes so far, and I think this may be what rings sour for me. The other’s woman’s devotion to “her man” is continuous with her devotion to their privilege. If she has a price to pay for her sins, he gets off scot-free, as usual. The woman’s choice is tagged as tragic. The privilege is hidden, hidden in plain sight, and thus protected from critique. The Great Gatsby, a novel that partners with the Great American Songbook, performs a similar sleight of hand, with its elegiac but diversionary final passage. It laments for the dreamers but leaves the dream intact.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

First, thanks for introducing me to this song. Second, thanks for alerting me to this album—now bookmarked in my Spotify account. Third, thanks for jolting me out of my afternoon listening habits and toward Ms. Simone!

Taking off my gratitude hat and putting on my critical cap:

On “Great American Songbook” compositions, and their tropes, aren’t you barking up the wrong tree—a bit—in complaining that they idealize certain conditions (i.e., the Mad Men world), and are conditioned by their historical contexts (which include the dreams, utopias, and problems of their times)? Also, even when they are really works of imagination, and largely escape their times, are you lamenting Robinson’s imagination *or* its limitations? I can’t decide if you wish Robinson was more conventional, and hadn’t dreamed up a vision that Simone’s sonic capabilities bring to life.

There are so many people we meet in songs and stories that are unreal. That is sometimes a blessing, and sometimes a cause for sadness. – TL

Tim, I’m not sure I’m tracking your question very well about barking up the wrong tree. Is there another tree to bark up? Or is it the barking itself, the complaining, or as I would put it, the identifying and articulating? A few days ago, Andy Seal posted an interesting piece about analyzing fiction, analyzing it aesthetically and analyzing it for its political underpinnings–and maybe finding some ugliness amongst the beauty. Maybe the latter is a bit of what I’m doing here. Without buying either category outright, I guess I do tend to think of the Great American Songbook as the soundtrack to the American Century, and the further the American Century is in the distance, the shorter it seems, both in length and in stature. At the same time, it doesn’t sense to me to wish any of them were any different than they are or that the artists who produced them had done anything differently than they did.

Now that you’ve found *Nina Simone at Town Hall*, you’ll note that “The Other Woman” is followed by “You Can Have Him,” a song by Irving Berlin, who is synonymous with the GAS. It offers the same story from the wife’s perspective. It’s also a very affecting song. But the devotion the singer expresses for “her man” is, well … see what you make of it.