About this time last year, a discussion ran on the blog on Ibram X. Kendi’s great book, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America

About this time last year, a discussion ran on the blog on Ibram X. Kendi’s great book, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America

. I returned to the book recently, going through materials for an African American History course. During roughly the same week, in preparation for the S-USIH conference in Chicago, in preparation for the two panels that were offered on environmental thought, I had the good fortune to read papers by Elesha Coffman, John Compton, Daniel Rinn, and Matthew Stewart. The result was that I couldn’t think about the latter without thinking about the former. Whether the merger between Kendi and the work of my S-USIH panel colleagues will lead anywhere, I don’t know. Maybe a reader of this post will have a helpful insight.

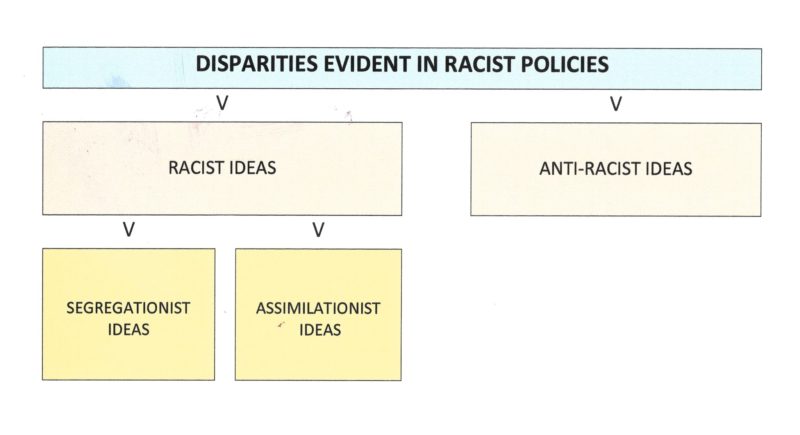

Kendi’s analysis emphasized several analytical moves that required some conscious adjustment on my part. The first had to do with the source of racist ideas. Kendi argues that racist ideas are not the result of ignorance and hatred but are developed in response to racist policies. Why this should be so isn’t given much theoretical attention in his book, but I think Kendi is saying that people are disturbed by the disparities that are the essence and the consequence of racist policies, and so they’re motivated to respond with thought–with criticism (anti-racist ideas) or with justification (racist ideas).

The concept is appealing. Richard Wilkinson’s and Kate Pickett’s book, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, makes a case for the social significance of disparity and how the response to it figures into matters as basic as health and happiness.

Experience teaching also weighs in. I wonder sometimes how my students explain racism to themselves. Talking about the Dred Scott decision just the other day, for instance, I read on their faces mixtures of surprise, confusion, and disgust. We can talk science, we can talk social construction, we can think of the racists we know in our own families and even of the racism in ourselves. But all that doesn’t necessarily answer the question about racism’s persistence or of its resurgence in national life during the past several years. Aren’t we getting smarter? Aren’t we making progress? And so on.

The second concept I drew from Kendi was his clear and irrevocable identification of assimilationist ideas as a species of racism. Anti-racist thinking, therefore, isn’t involved in a binary conflict with racism. Rather, anti-racist ideas battle with a two-headed monster, a good-cop-bad-cop duo of assimilationism and segregationism.

Here’s a graphic representation of my understanding of Kendi’s analytical frame.

The third concept I drew from Kendi is to think of these different species of ideas as actual or near-actual species–as living entities that evolve, go dormant, change form, and adapt according to conditions. It’s too simplistic–and we might say, hubristic–to think that they can be eradicated solely by rational argument or better information. They live. They grow. What’s more, an individual can harbor a variety of racist and anti-racist ideas, in the manner a body holds parasites, sometimes beneficial, other times not.

The third concept I drew from Kendi is to think of these different species of ideas as actual or near-actual species–as living entities that evolve, go dormant, change form, and adapt according to conditions. It’s too simplistic–and we might say, hubristic–to think that they can be eradicated solely by rational argument or better information. They live. They grow. What’s more, an individual can harbor a variety of racist and anti-racist ideas, in the manner a body holds parasites, sometimes beneficial, other times not.

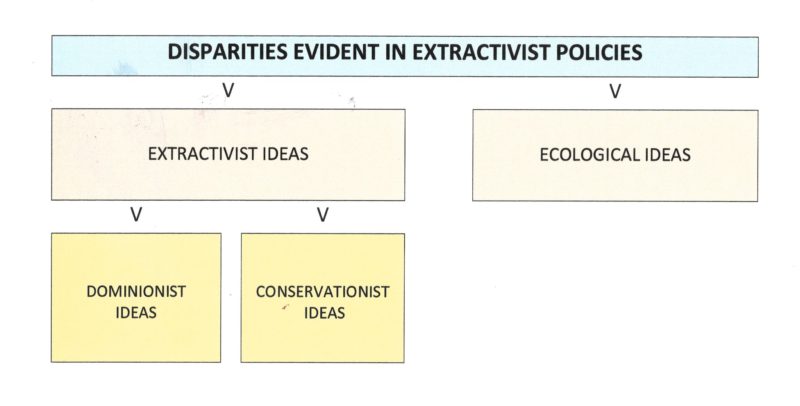

Now, I may not have gotten Kendi just right. I might need to be schooled a little. But I hope it’s clear that his analysis has been fruitful for me. I wondered, could I take his analytical frame and recode it onto environmental thought? As a simple thought experiment, could I use this new frame to break up old frames and old ways of seeing?

One of the conference panelists was John Compton, a professor of political science at Chapman University. His paper triggered the experiment. Its title was, “‘If You’ve Seen One Redwood, You’ve Seen Them All’: Lynn White and the Decline of Protestant Stewardship in the Long 1960s.” Chapman used Lynn White, Jr.’s seminal 1967 article, “The Religious Roots of our Ecological Crisis,” as an opening gambit. From there, he detailed a rift, contemporary to White’s article, between evangelicals and mainline Protestants in Southern California concerning the proper relationship between humankind and the environment. White had charged that the environmental threats Americans were confronting had their origin in the book of Genesis, with its verse about “man” having “dominion” over the fish, the birds, and “every living thing that moveth upon the earth.”

This put things a bit too simply, many critics have since pointed out. Mainline Protestants had a long tradition of understanding God’s people as stewards or trustees of the living earth and its resources. This could already be seen in, to name a common instance, the Good Use or Conservationist policies of Gifford Pinchot, Chief of the United Forest Service under Theodore Roosevelt.

Compton’s paper traces the mobilization of a more radical approach, one that stressed dominion. This new dominionism (my word) was woven into Ronald Reagan’s platform when he ran for governor in 1966 and that he continued to advocate as US President. The stewardship/conservationist camp recognized that humans had a God-given responsibility to care for the sacred earth, to manage its resources so that they would be available for later generations. In contrast, the dominionist view might be summed up this way: non-human nature had no rights that any human was bound to respect.

Compton’s paper may have been the trigger, but the papers by Coffman, Stewart, and Rinn played a role, too. Each was smartly argued, beautifully detailed, thoroughly sourced, and a great pleasure to read. Yet when set by side with each other, when set amongst the historiography of environmental thought, a certain abstraction is inevitable. What emerges is a handful of ideological battles, battles that grow stale with repetition: anthropocentric ideas versus eco-centric ideas; conservationist ideas versus preservationist ideas; social ecology versus deep ecology. What a reader longs for is new light.

That’s when the experiment to recode Kendi’s frame onto environmental thought took shape. Here it is in graphic form:

Certainly, there are problems here. This recoding may be useful or not. I’ll need more time, or maybe a little help, in seeing how.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Very interesting, thanks for this.

First, I think your brief summation of Kendi is a solid one. “Kendi argues that racist ideas are not the result of ignorance and hatred but are developed in response to racist policies.” I have this conversation with my students all the time – which came first in America, racism or African slavery? While it is hard to imagine that slavery could have come into existence without some initial racism, it is easy to see that racism in America has been exacerbated and fueled by slavery. In this way, whatever initial racist ideas were held that allowed people to enslave Africans, later generations who only saw the results of that policy came to only know that version of Africans – the ones who were degraded and dehumanized by slavery. So those generations believed the slave condition to be the natural condition of Africans and their descendants, this led to making more policies that continued the cycle of racism. Kendi’s schema has been very influential in my thinking since reading the book and I will be using it again next semester.

I think that your idea that something similar in pattern or schema can be seen in our approach to the environment is a useful one. That there is a style of conservationist thinking that is not on the same side of the fence as ecological thinking. Not that there is any particular link between racism and extractivism, nor is this recoding the end of the discussion, but it opens up ideas about where to place different policies or thinkers (and the origins of those ideas) into the broader debates over the environment – which I think is what you are after there.

Thanks you, Bryn, for engaging with this post. Although it is decades old, Carolyn Merchant’s book The Death of Nature still influences the way I think about the development of extractivist ideas. She writes about a period when new economic orders called for, and new technologies allowed for, the extraction of materials of new kinds and at new levels of scale, both above and below the surface of the ground and sea. The sheer ugliness of such processes must have been (and continues to be!) deeply disturbing. New ways to think about nature (and in association, women) were constructed to justify this ugliness. The thinking that provides for the ruthless exploitation of human beings and the thinking that provides for the ruthless exploitation of the living earth may indeed be linked on some level. But the most controversial, and perhaps useful, result of my recoding is the one you identify: the possibility of parallelism between assimilationism and conservationism. There was a time when many would have bristled at the suggestion that assimilationism was a kind of racist idea. (After Stamped, that seems much less possible.) The claim that conservationism is a kind of extractivist idea would surely meet what may be a similar resistance.