Editor's Note

This post is part of our Critical Connections series, highlighting new or forthcoming works of historical scholarship that connect to current conversations and issues of widespread concern within American thought and culture. You can read all the posts in the series by clicking on this tag/label: Critical Connections

I am going to tell you some things that I remember and remind you of some things I still believe in – or want to.

If you teach the history of America’s war in Vietnam and its brutal aftermath like I do, you probably know some of this story. There was the open war, and alongside it the secret war, fought in the mountain terrain of Cambodia and Laos, even after America’s formal withdrawal from Vietnam.

America’s staunchest allies in that secret war were mountain highlanders who call themselves Hmong, meaning, “free people.” When Saigon fell, and it became clear that Cambodia and Laos as well would fall to Communist forces, the American military and the CIA were drawing up plans for the evacuation of a few of these key allies – high-ranking officers in the Lao Army, their immediate families, and the soldiers under their command. Even though the Pathet Lao forces captured the encampments that had served as gathering points for thousands of Hmong, a few thousand of these American allies were evacuated to safety, first in refugee camps in Thailand, and then to the United States.

Those who were left behind had to flee for their lives.

The Hmong are a distinct ethnic group among the peoples of southeast Asia, with their own language and faith traditions and agrarian culture, tracing their kinship through a couple dozen family lines. As American allies, they were marked men – men, women, and children, marked for death. They were pursued as they fled by foot and by boat, as they swam across rivers. Those lucky enough to survive the harrowing, deadly journey – and so many were not – gathered in refugee camps in Thailand. In 1980, America reached an agreement with Thailand and passed legislation to allow thousands more of these war refugees to settle in the United States.

The Hmong are a distinct ethnic group among the peoples of southeast Asia, with their own language and faith traditions and agrarian culture, tracing their kinship through a couple dozen family lines. As American allies, they were marked men – men, women, and children, marked for death. They were pursued as they fled by foot and by boat, as they swam across rivers. Those lucky enough to survive the harrowing, deadly journey – and so many were not – gathered in refugee camps in Thailand. In 1980, America reached an agreement with Thailand and passed legislation to allow thousands more of these war refugees to settle in the United States.

My hometown was not one of the cities selected for Hmong resettlement. But in the early 1980s, and especially over the summer of 1982, thousands of Hmong refugees came to our farm town, and kept coming for several years after that.

They came because it was a farm town, because they wanted to resume their way of life as farmers, living in close community and working the land that provides a common sustenance to all. That they could not farm without title to the land, or a lease on it, was something many learned only after they arrived.

Hmong families, like all immigrant families who try to live near one another and assist each other and depend on each other, found housing where they could – on the fringes of town, on the south side of the tracks, in old and decaying neighborhoods, in apartments when they had to but in little A-frame houses where they could, turning the wasteful ornamental sterility of front lawns and back yards into massive vegetable gardens, growing varietals from precious handfuls of seed stock they had harvested and kept for the day they could be rooted in a place again. Every vacant city lot on the south side became fertile farmland again.

The land they came to welcomed the Hmong; the people around them mostly did not.

Not at first, anyhow.

Now I am going to tell you some ugly things I remember.

I remember the rumors about “the Laotians” coming to town, rumors flying around the schoolyard, rumors whispered in grocery stores, rumors printed in the newspaper. They practice witchcraft. They don’t bathe. They keep pigs in their house. They bring disease. They bring lice. They smell – even if they wash, they smell. They like living crowded together, twenty or thirty to a house. They eat cats and dogs; neighborhood pets have gone missing, and it must be because the Laotians are eating them.

That last rumor – and plenty of the others – ran in the hometown newspaper. I remember reading the article. I don’t remember the headline, but I remember the gist of the article, including quotes from “concerned residents” whose cats or dogs – or the cats or dogs of someone they knew, or heard about, or something – had disappeared, and “some say” the immigrants had trapped them and slaughtered them for food. It may have been more than one article.

I didn’t know I was reading “yellow peril” slanders more than a century old. But I knew that a lot of people in town, including a lot of people in my extended family, ranged from suspicious to alarmed to downright hostile to these newcomers, these refugees fleeing the disastrous aftermath of America’s disastrous war.

I remember my great-uncle Walt, sitting hunched over and leaning forward off the edge of sofa in my grandma’s A-frame house, grimacing through the billowing cigarette smoke, taking a draw, grimacing again, and then saying to my grandfather, “These God damn Laotians with their God damn crooked tongue.” He took another drag. “They’re God damn everywhere. Like a bunch of God damn cockroaches.” No one interrupted Uncle Walt when he was on a bender or a tear. “If there’s one, there’s fifty.” Then he took another drag and exhaled. “It’s a God damn invasion.”

As I type out those words, I can hear his voice saying them over again – Uncle Walt, the angry brawling drunk belligerent uncle, so hateful and racist and sexist and mean that it was almost cartoonishly over-the-top. Almost. He was a mean old sonofabitch, and he automatically and vigorously hated anybody who wasn’t white, and quite a few people who were.

Take that hostile voice, that hostile xenophobic ungenerous heart, and multiply it by a few thousand, and you perhaps have some sense of what the Hmong refugees faced when they came to a farm town that wasn’t expecting them and didn’t want them.

Not everyone was like that, of course. My parents weren’t like that, thankfully. My dad had become a high school teacher, and my mom got a part time job as a reading aide in the elementary schools to work with non-English-speaking children, and I know that their experience in working with Hmong children made them warmer and more welcoming people than they might have been otherwise. But lots and lots of perfectly respectable people in town were not just ignorant or curious, but wary, resentful, angry, and often inhospitable. My parents had friends who moved to another state

in the early 1990s because they were so angry over the presence of this new immigrant community with large, tight-knit families and children coming into school who spoke no English.

Of course, the school system in our town was the route to assimilation for the Hmong community, as the public schools have been the route to assimilation for every immigrant community. Prop 13 had already gutted school funding, and resources were stretched thin, but within a couple of years – thanks to state waivers that allowed for ESL classes in lieu of bilingual courses, because there were no teachers to be found who could teach these children in their own language – the Hmong children and young teenagers who had come to town were working with tutors and reading coaches and soon sitting right beside us in our crowded classrooms, changing beside us in the locker rooms at PE, standing beside us in line to meet with the high school guidance counselors.

There was just one high school in the town, serving the city and the surrounding farmland. Out of my graduating class of about 540, there were about 50 Hmong graduates – about ten percent of the class. By the time my youngest sibling graduated, thirteen years later, our town had built a second high school. At her graduation ceremonies, families were welcomed in three languages: English, Spanish, and Hmong. It was one of the most amazing things I had ever heard – thrilling, honestly. In little more than a decade, my boring old home town in the middle of “the Other California” had become cosmopolitan – and to the extent that racist people who could not abide the presence of these newest immigrants had closed up shop and left, it had become that much better.

The children and grandchildren of the first generation of Hmong immigrants, the children of my high school classmates, are pillars of the community not just where I grew up but wherever Hmong families settled in large numbers – in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, the Carolinas. Any city in America with a sizable Hmong community is blessed with ambitious and dedicated American citizens who have overcome extraordinary obstacles to re-enact the great pageant of “the American dream.”

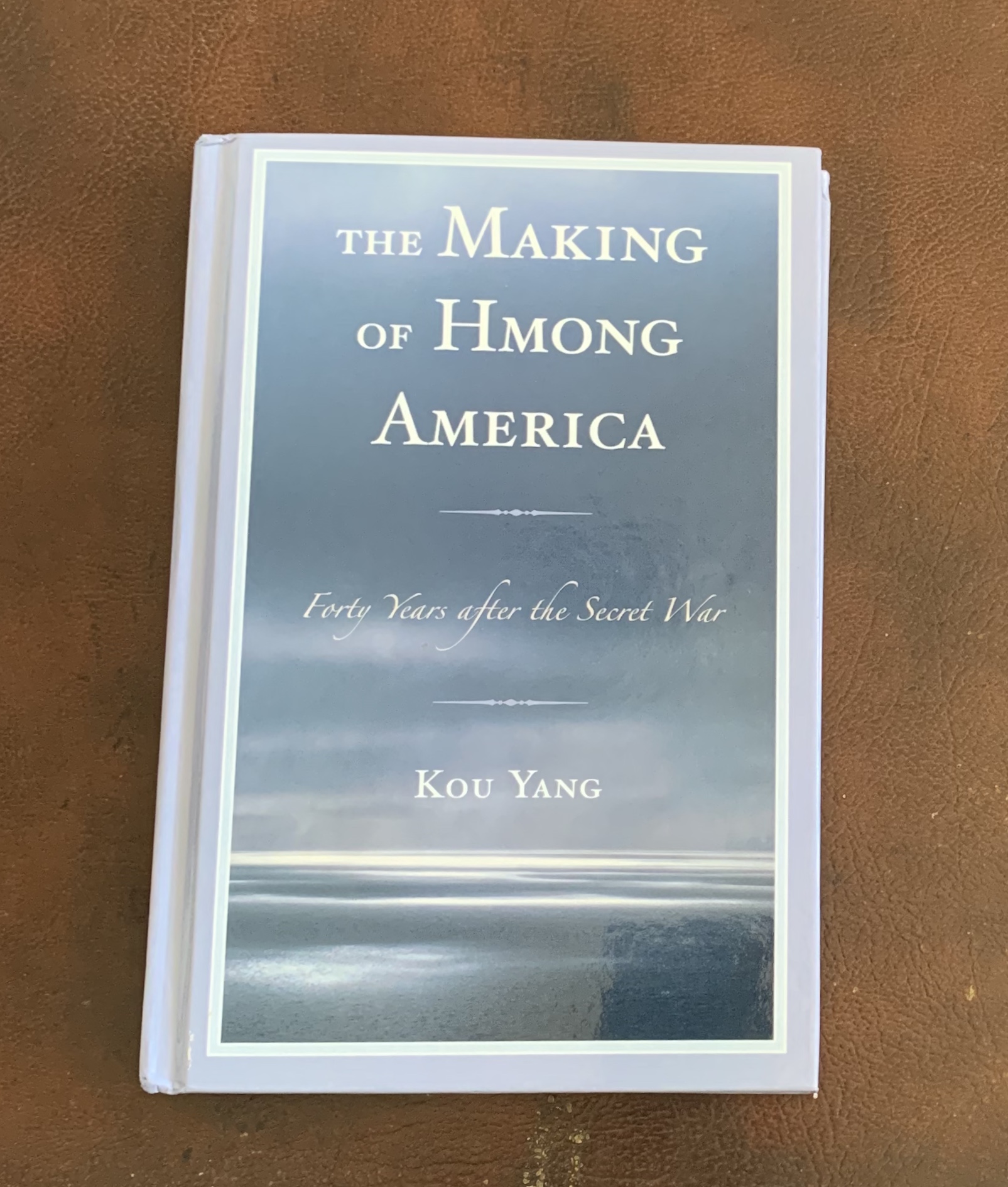

You can read all about the growth and establishment of the Hmong-American community throughout the United States in The Making of Hmong America: Forty Years after the Secret War

, by Kou Yang, professor emeritus of ethnic studies at California State University, Stanislaus. Today Hmong-Americans are doctors, lawyers, judges, scientists, college professors, high school teachers, managers, accountants, business owners, farmers, grocers, soldiers and sailors. They are Americans. They are here because their grandfathers and their great uncles fought side by side with American soldiers, and that alliance cost them almost everything.

Now, more than forty years after the fall of Saigon, forty years after the communist forces of the Pathet Lao conquered the highlands and pursued a genocidal war of revenge against those American allies, prompting the flight of tens of thousands of immigrants to safety in the United States, there is talk of a change in immigration policy, a change in status for some of these immigrants.

I went to high school with those immigrants — teenaged boys and girls who saw their siblings drown, who saw them shot, who lost grandparents, aunts and uncles, parents. They spent years in refugee camps. America promised them refuge. They came to my home town with nothing but their kinship and their faith and their will to work. Exiled from their homeland for being loyal allies of the United States, they came to my home town, and to other towns and cities across America, because they had to. As they found and made a home for themselves here, they made home for all of us better.

That’s America’s promise. People have fought for it. People have died for it. Whole families have faced death, suffered loss, to join in this promise – to enlarge it, to contribute to it, to make it shine brighter.

Refugees are still fleeing from the violent cataclysmic aftermath of America’s secret and not-so-secret wars in their homelands. The rippling waves of violence from American foreign policy decisions and U.S. military maneuvers and CIA operations carried out decades ago are still wreaking havoc and sending people fleeing from their homes, fleeing for safety – across rivers, across mountains, across deserts, they make their journey here. Because somehow, incredibly, despite the ugliest expressions of racism and the most sordid cultivation of overt xenophobia as policy and law that this flawed nation has seen in decades, this country still

stands for something for the people who are trying to come here: America stands for the hope of something better for their children.

That was the American dream for the Hmong, and it is the American dream for refugees today.

A little girl of seven years old just died of heat exhaustion and dehydration on the way to reach that dream. A child died of thirst on American soil, a child in America’s custody but not in America’s care.

It is past time for this nation to start living up to its promises – the promises we have made, the promise that we say and believe we are.

“We shall be as a city on a hill…”

Shall we?

Then we had damn well better start shining.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

When you first mentioned you were going to write about this, I thought long and hard about sharing a personal story that relates to the post-Vietnam War immigration of Hmong and other groups from Vietnam to the U.S.

I remember, back in the late 1990s (or perhaps early 2000s–I’m not precisely sure) being with my parents in a local Sam’s Club in Georgia. We ran into one of my dad’s friends from the police force. He was Vietnamese American. He and my dad exchanged pleasantries, laughed a bit, he said hi to my mom and I, and he was off.

An older white gentleman came up to my dad and said, “They’ll let anyone in this country, won’t they?”

My dad quickly glared at him. “Did you know he fought in the South Vietnamese Army, came to this county, served as an ARMY RANGER, and is now a police officer?”

The older gentleman quietly scurried off.

Your wonderful post reminded me of that. I don’t have much more to add in terms of historicizing what happened. I could go into the shared experiences of African American soldiers during Vietnam, and how many of them fraternized–in various ways–with the Montangards during the war (something chronicled in the oral history collection *Bloods* and I nearly wrote about this past week). I could go deeper…but I just had to tell that story.

Robert, thanks so much for sharing that story. I can’t imagine that anybody of rank in the U.S. military or at the Pentagon thinks that changing the status of refugees from the Vietnam war would be a good idea. American soldiers are deployed all over the world, in all kinds of situations, and their safety and very lives often depend on the relationships they build with allied forces in those places. If the United States rescinds a promise of refuge it made forty or fifty years ago to staunch allies, how can local forces on the ground now trust the promises of the U.S. military to stand by those who stand by them? Whatever anybody thinks of current wars or war in general, it is the case that many of our fellow citizens are placed in graver danger by these asinine nativist gestures.

What’s so important to know about the Hmong people in particular — and I should have mentioned this in the piece above — is that, unlike the South Vietnamese, Cambodians, and ethnic Lao, the Hmong were considered not suitable for immigration to the United States because of their culture. They were an oral culture, without a writing system for their language, completely agrarian, “undeveloped” in the sense of having no modern conveniences or facilities. American soldiers trusted the Montagnards with their lives, and they damn sure knew that those men could handle a gun and a two-way radio, but somehow the broad conclusion of some officials was that the Hmong were “unassimilable.” That’s why Prof. Yang devotes so much of his text to documenting the successful assimilation of multiple generations of Hmong immigrants.

It’s not immigrants who are “unassimilable,” but nativists (themselves descended from immigrants) who can’t adjust to or abide the experience of difference.

That’s not to minimize the culture shock for Hmong immigrants, especially, I think, around matters of religious belief and practice. Hmong-Americans are a transformed people, certainly, but they are also a people who have transformed America for the better, as has every immigrant group who has come here — with the possible exception of these second-rate public intellectuals and right-wing provocateurs who keep crossing the pond from the UK, hoping their dazzling accent will give them enough gravitas to work the grift for a while among the rubes in America. I’d like to think that Milo, Piers, Mr. Proud Boy, Sullidish, Nigel the Brexiteer, and all their epigones are unassimilable, but they all seem to be tooling along just fine in their crowded, crummy lane.

Anyway, for those interested, there’s an open-access peer-reviewed journal, Hmong Studies Journal, in publication since the mid-1990s, that offers a wealth of information and insight into this very important, transformed and transformative immigrant community and quintessentially American story.

Here’s their website: https://www.hmongstudiesjournal.org