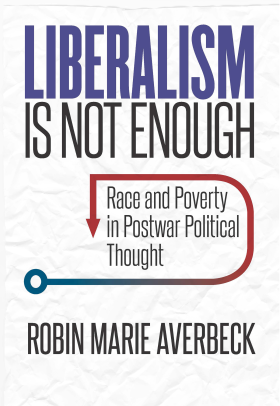

About three years ago, I began the journey of turning my dissertation into a book. This is one among several reasons why I more or less disappeared from this space – but with the book done I hope to recommit myself to appearing here at least once a month. I’ll start out, however, with something a bit different from my usual bloviating and instead try to produce something helpful for you

which, research has indicated, are some of the most popular posts at the blog. (Fancy that!) I will simply relate my process and experience, since I do not know how common or representative they might be, and avoid offering too much advice. Take what you think might be helpful or useful for you, and feel free to ignore the rest!

The first part of my process was making clear to myself what was my vision for the book. Fortunately I knew the most fundamental aspect of this from the beginning: I wanted the argument to be stronger, fully in-your-face political, and I wanted it to structure the entire book, not merely tacked be on at the end and beginning of chapters like poorly lighted signposts that said, “So!, incase you were wondering this is what you should take out of all this information…”. If reviewers don’t call this polemical, I thought to myself, I didn’t do it right.

Writing my proposal helped me sort through the details of what this would look like. Out of that proposal I wrote up a short, 300 word bullet list of everything that would change, and everything that would be added; I tacked it to the wall in my office behind my computer, so whenever I was working, I could quickly reorient myself to What The Fuck Am I Doing Here when details, logistics, and the length of the goal ahead threatened to overwhelm. That simple bullet point list helped me keep my eye on the ball throughout the entire process, and also had a calming effect – oh shit!, I would suddenly think, have I gone astray? A quick glance at that list of priorities would usually be enough to think, nope, it’s ok, we’re still on the right track.

The work began with reading some new sources, rereading some old ones and revisiting my dissertation, page by page. While I was doing this last task it became evident to me how much I was going to cut out of the dissertation – while, say, the history of the sociology of the city in the 1930s is interesting and ultimately relevant, it did not immediately speak to my main concern, the nature of postwar liberalism in the context of the 1960s. What I did not necessarily expect was the delight of cutting material – with a PhD and book contract in hand, gone were any self-doubts about needing to insert signposts testifying to my familiarity with the historiography or the depth of my research. If it was not necessary to the core mission of the book, it was sacrificed at the altar of the god of I’ve Got This.

Facebook post from when I was writing Chapter 2, which ended up being a combo of two chapters I cut a ton of stuff out of.

This was related to a second goal I had for the book: accessibility. While I had no illusions about it reaching a broad popular audience, I did hope that should anyone without a postgraduate education pick it up it could be easily understood. My editors helped me out in this regard (among many others): one suggested using a word or phrase other than “discourse,” a tall order considering that nearly the entire book is about discourse. But I had to agree: “discourse” is one of those red flag words which, when non-academic folk hear it, might lead to the cocking of heads and an irritating feeling that whoever is using this odd phrase is talking down to you. So, I ended up having a decent amount of fun coming up with different words and phrases less abstract than “discourse,” including “meme,” which far from being merely a trendy slang word amongst millennials is, I think, actually quite useful!

Once I had a clear idea of what was – and was not – going into the book, the writing could begin. Chapter by chapter, I followed the same process I always have for writing anything: I reread all my notes and evidence, I draw up a detailed outline, and then I go back and choose which evidence to use per paragraph. (This last step I call The Culling, which has the double virtue of motivating me with a sense of gravity at the beginning of the task and making me giggle.) Of course, changes are always made in the execution of the thing; but on the whole, the process did not vary at all from my earliest days of composing high school papers. (A fact in no small degree due to my amazing high school English honors teacher, who taught me 75 percent of all I’ve ever learned about how to write. It was a particular pleasure to send her a signed copy.) The actual experience of writing was a pleasure and a joy – not surprisingly, it surpassed any previous writing experience I have had, considering how resolutely I was in the driver’s seat and how much of my heart and soul it represented. Plus, it was going to be a book!

The next step – copyediting – was, I confess, less of a joy. This probably had not a little to do with the particularities of my schedule (I was teaching at the time), leading to a situation where I reviewed all the copyediting in a coffee shop on the top of a hill in Haifa over the course of a week. Due to this rush, there was things missed I had to go back and correct later, so if I would offer any specific advice in this post that I’m confident does not only apply to me and my own habits and tendencies, it would be this: leave plenty of time for copyediting! Yet I got through it, and had one more chance to apply edits, when the page proofs became available. Since I did not have a proofreader, I approached the problem of catching my own typos by reading out loud or mouthing every single word in a monotone, choppy syllabic rhythm while tapping my pen on each word as I read. I have no idea if anyone has ever done this before in the history of book writing, but although I can’t recommend it for efficiency, it did do the trick. (It helped a lot that the book is quite short. I can’t imagine doing this for 350+ pages.)

The rest, as they say, is paperwork. My only major suggestion for those taking on this seemingly daunting task is to trust yourself and your experience: a book is merely a lot of essays about (roughly) the same thing, so whatever has worked for you in the past, is probably going to work for you here. And remember: it’s worth it.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thank you for this post on your writing process and experience. Looking forward to reading your book.

Congrats on the book, Robin! I expected nothing less than an in-your-face, well-done, polemical history from you. – TL

Congrats. Your mentioning the book’ s brevity increases the chance of my reading it.

Robin, congratulations on your book! I look forward to reading it. I appreciate your attention and model protocol in The Culling, and I empathize with copy edit duties. One recommendation to add: Think critically about your construction of the index. It’s often the first thing that readers flip to, so draft a few overarching editorial strategies that will make your text easy to navigate–and cite.

Congratulations! I look forward to reading it!