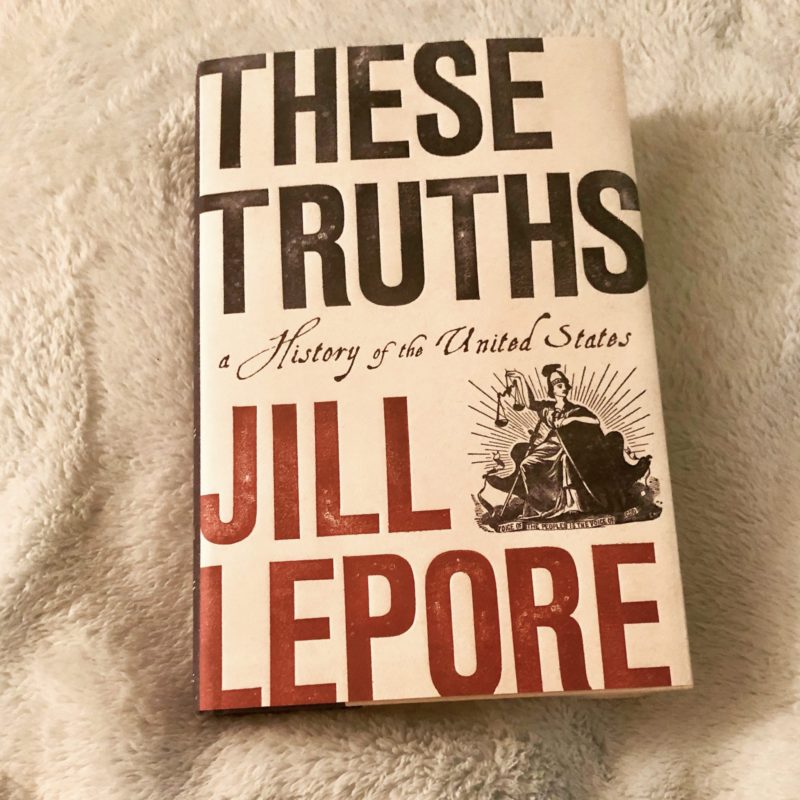

What is the true history of the United States? The story of the early American republic changes depending on who you ask and where you learn it. Cities like Boston, Philadelphia or Williamsburg can be the birthplace or cradle of the revolution. When discussing our history or we the people, different Americans feel included in that to various extents today. Yet, historian Jill Lepore’s 2018 book, which marks the first attempt by a woman in modern history to encapsulate the history of the United States in a singular volume, is titled These Truths

.

Following her book’s release, Lepore made headlines with a Chronicle interview, reflecting among other things on the story of the United States as a philosophical experiment. Lepore contends that the “United States was founded quite explicitly as a political experiment, an experiment in the science of politics” and thus, the story that has unfolded represents the findings of that experiment. In the same interview, Lepore frames a dichotomy of “academic historians saying American history consists of conflict among groups who are generally powerless relative to the federal government,” versus “a public history that is about the power of the presidency and that ignores conflict among groups.” For Lepore, both the academics and the public, each as “partisan” as their counterpart, present only a partial truth.

Scholar, writer, and USIH blogger Holly Genovese responded

that academic historians engage diverse audiences, the “public,” too. She questions who does Lepore think the “public” really is? As Genovese notes, multiple audiences consume history. The fields of public humanities and public history have interrogated these questions and strategized reaching broader audiences in a sophisticated manner. Genovese writes: “Are college students the public? People with non-academic professional degrees? My grandma? Nobody seems to know, making it seem… that all of us… may be trying to reach different publics.” Her outstanding USIH post reminds readers not only that there are many publics, but also that public history and public humanities are flourishing fields doing this work. Some public history professionals do not even engage formally with “the field” as we know it, but instead they cater to patrons within their communities. Thus, Genovese reminds historians and all students of history that countless audiences exist.

But for countless audiences, how many truths? Lepore’s nearly 800-page masterpiece These Truths represents a modest attempt to define the nation. I call it “modest” because she states in her introduction and the interview that she has attempted an impossible task. She writes: “These Truths: this was the language of reason, of enlightenment, of inquiry, and of history” (xvii). She claims that “the beginning [of this story] has come to an end. What, then, is the verdict of history? This book attempts to answer that question by telling the story of American history.” She adds: “Wars it has waged since 2001, when two airplanes crashed into the two towers of the World Trade Center eight blocks from the site of a long-gone shop where the printers of the New-York Packet had once offered for sale a young mother and her six-month old baby” (xviii). In the same space, a terrible attack on America happened, where 200 years previously, Americans had sold humans.

In addition to physical space like this New York example, Lepore uses chronology to bridge the divide between the heroes and the martyrs, the oppressors and the oppressed, the powerful and the powerless resisters, or how Lepore might view it, the academic historians and the popular biographers. For instance, George Washington’s “beauty was marred only by his terrible teeth, which had rotted and been replaced by dentures made from ivory and from nine teeth pulled from the mouths of his slaves” (120). Lepore fuses her presentation of mythical figures such as Washington with brutal realities, epitomized by tearing from enslaved persons something as personal as teeth. Possibly between his leadership in the American Revolution and his tenure as President of the United States. Some care because this was Washington, while others focus on the oppression that their ancestors endured. Lepore strives to combine these perspectives into one story. But if multiple audiences consume history as Genovese points out, then how specifically do multiple publics share “these truths?”

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

But if multiple audiences consume history as Genovese points out, then how specifically do multiple publics share “these truths?”

Rebecca, this is a great question, a fine way to wrap up a wonderful debut post. Thanks for writing!

I guess we need to conceive of a Venn diagram that might indicate where some/most of these multiple publics overlap. That would have been easier to draw 50 years ago, even 40 years ago — the fractured media landscape following the rise of cable and the repeal of the fairness doctrine has become a completely pointillist media landscape, with each person’s reception of ideas customized either by themselves or (more insidiously) by algorithms that curate content for us all.

It seems to me that athletics and the arts (broadly construed) are the two “places” in our social lives that reach/include people from many different publics. Even academics enjoy sports and movies. Yeah, there’s always that one doofus who is very performative about how they “can’t imagine wasting time watching television” or will tweet derisively about “something happening in sportsball” during the World Series, but most of us are people, just like the people in the other publics. Movies, TV (including this newfangled bingeable made-for-internet-streaming TV writing), NCAA sports, professional sports, major spectacles (spectacle is key) — that’s where lots of publics intersect, still.

What are “the truths” about America that are expressed in/through those venues? Meritocracy, dedication, sacrifice, patriotism, U.S. military as a force for good in the world, “American values” (lots of small-town / heartland stuff — I’m thinking of all the profile bios of Olympic athletes that air before their events) — those are some explicit themes. In terms of specific ideational content, I guess Wealth of Nations, Acres of Diamonds, or The Power of Positive Thinking may show up more in what is on offer than the Declaration of Independence does.

But that’s me being cynical. When I’m feeling more hopeful, I can hear other registers in the cacophonous symphony of our public discourse, broadly construed.

Thanks for your thoughtful comment! Publics that first come to mind for me: people who’re retired & consume history in leisure time, children on field trips learning history for 1st time, educated non-historian bookworms who read a bit of everything, people reading books while incarcerated, history graduate students, etc. Might even be overlap among these. Each consumer of history combines various reasons for learning. So I don’t think there’s one true narrative that serves all of the above, but I admire Lepore’s endeavor!

Rebecca, I admire the fact that all your publics are reading publics who are interested in learning and tend to do so via reading (which is, I guess, a safe assumption if we’re talking about the kind of public that might be reached by a book).

I wonder — and don’t know the answer — how much history (sound or dubious) is conveyed by non-textual (or at least non-script-based) means. Between Crusader Kings, Sid Meier’s Civilization games, and the Assassin’s Creed franchise, there’s a penumbra of historical factoids, and even perhaps particular historical narratives / perspectives, that makes its way into the world of gamers.

As I learned when I returned home for Thanksgiving, a/the big thing now is something called “Red Dead Redemption II” — I think there was even something about it in the NYT Arts or Style section recently? I came home to a house full of people ranging in age from their 50s to their teens who watched each other play this game for hours. Eventually I sussed out of them the following (probably garbled) info: the game is “set in the 1890s,” in terms of technology, “in the American West, but after the frontier is closed,” and apparently features real places in American topography (this last part I am dubious about) but with fictional town names and utterly devoid of “real” American history. So you get “the West” when “the law” is trying to “civilize” the place, but there are no Native Americans (or at least no fighting against them), apparently no African Americans (not sure on this — I did not sit and watch people play video games for hours), and the only women are NPCs, including a very friendly barmaid who offers an extra special bath. (Kid: “You have to take a bath once a month or your health runs down.” Me: “Well, I’m glad that lesson finally took.”)

In any case, these sorts of pastiches of the topographical, the historic, the legendary, and the imagined in video games probably shape young peoples’ view of the past as much as or more than films do these days.

I wonder how one could “gamify” the survey, and how one could make it work for those who can’t stand to play a game in “story mode.” But this is idle curiosity on my part, because I wouldn’t be the person to do it. But I do think it’s worth doing, because this visual narrative realm is only going to become more ubiquitous.

At the same time, I feel like our job is to be those NPCs, standing with our stacks of books and papers and text, text, text, and offering people a respite from the hyper-real world of gamified knowledge.

Anyway, great post and great pushback in comments!

What if the truths are not true? When I got to the pages about Zuni, I hit the pause button, primarily because of her use of a quote that has no credibility. https://americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/2018/11/not-recommended-jill-lepores-these.html