I just finished an Honors Reading Group on Julilly Kohler-Hausmann’s Getting Tough: Welfare and Imprisonment in 1970s America. Kohler-Hausmann’s book is an excellent policy history that focuses on three case studies: the Rockefeller drug laws in New York, Ronald Reagan’s reforms to welfare in California in the early 1970s, and the transition from indeterminate to fixed prison terms in California in the mid-to-late 1970s. Like many of the best policy histories, Getting Tough’s material largely lies at the intersection of social history and political history. But intellectual history is also an important part of Kohler-Hausmann’s narrative, which is, among other things, about shifting self-understandings of drug users, welfare recipients, and the incarcerated as well as shifting ideas about them on the part of other citizens and politicians.

Kohler-Hausmann argues convincingly that, far from advocating for “smaller government” or a reduction in state power, conservative critics disagreed with liberals less about the size and power of the state and more about its proper use and the proper objects of its power. Conservatives in the 1970s reoriented drug, welfare, and sentencing policies from attempting to reintegrate drug users, the poor, and the incarcerated to marginalizing those populations and excluding them from full consideration as citizens.

The most striking of Kohler-Hausmann’s three case studies is the final one on sentencing. California inmates in the late 1960s and early 1970s detested that state’s indeterminate sentencing system, which they saw as capricious and inhumane. Incarcerated prison activists lobbied for fixed sentencing and provided important political impetus for its eventual adoption. But fixed sentences immediately brought with them political pressure to lengthen them. Soon, the legislature stopped soliciting testimony from inmates. And, within a few years, the vital prison newspapers that inmates published, which had been an important part of the public discussion of sentencing in the early 1970s, were also shut down by the state.

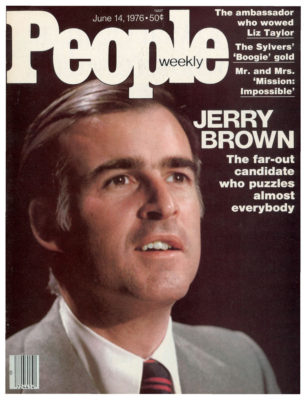

California’s move to “get tough” in sentencing in the mid-to-late 1970s was bipartisan. Overwhelming majorities in the legislature passed ever tougher sentencing laws. And Governor Jerry Brown was anything but a stereotypical liberal on criminal justice issues.

Kohler-Hausmann concludes (on p. 284):

While many present Democrats as unwitting accomplices in penal expansion, these dynamics might better be interpreted as evidence of a broad consensus about the political and social disposability of racialized, criminalized groups for many in both parties. Lawmakers across the political spectrum were willing to sacrifice prisoners’ interests for political gain or protection. Just as the worst excesses of McCarthyism depended on the broad consensus about the dangers of communism, the most extreme “tough-on-crime” policies were predicated upon acceptance of the appropriateness of criminal targets and their subordinated status in the polity.

This passage is, I think, only half right. Her evidence suggests not so much that (nearly) everyone across the political spectrum shared a commitment to the “tough” policies California adopted, but rather that once political majorities came out in support of these policies, nearly everyone else in the legislature seems to have calculated that it wasn’t worth their political while to oppose these changes. The McCarthyism comparison seems very apt to me…though again I don’t think it suggests quite what Kohler-Hausmann argues that it does.

A willingness to see people’s careers destroyed (under McCarthyism) or felons’ civil rights denigrated (under California’s “tough on crime” laws) is not exactly the same as actively supporting these things. Kohler-Hausmann is right to see a consensus among California politicians in the 1970s about the political and social disposability

of certain groups. But being willing to dispose of certain people for one’s own political gain is not quite the same thing as seeing those people as an actual social threat. And understanding the political cowardice of those willing to go along in these circumstances seems to me to be a crucial historical task. I think we have a better understanding of citizens and politicians who embraced a purely punitive understanding of incarceration and worked to social marginalize convicts than we do of those who did not share these beliefs, but were nonetheless willing to “get tough” as a matter of political pragmatism.

American history is, of course, littered with people who have made similar calculations – about slavery, Jim Crow, the Iraq War, and countless other issues. It’s easy to see this species of political cowardice as something other than what it is, either as tough-minded pragmatism in the face of politically challenging circumstances or, alternatively, as simply a less honest endorsement of unpleasant political positions.

But I think such political cowardice requires its own explanation.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

A note re Jerry Brown. When he ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1976, one of the things he said was that “we’re going to move left and right at the same time” (a line that struck me as rhetorical gibberish, and still does). So I’m not surprised to learn that he was not, as the post puts it, a stereotypical liberal on criminal justice issues in this period. He did not present himself, at least during the ’76 campaign, as a stereotypical liberal. That might have been a matter of conviction or it might have been a pragmatic calculation that the Democratic primary electorate of that year was in the mood for vague mush. Anyway, today’s Jerry Brown seems different from the Brown of that period, at least in terms of how he presents himself on the national stage.

That’s absolutely correct. The young Jerry Brown in the 1970s was totally mercurial. Sometimes he seemed to simply follow his own, often difficult-to-pin-down, conscience. At other times, he seemed to drift with the political winds. On, e.g., criminal justice issues I think it was more the first (so he’s actually not an ideal example of simple cowardice in that regard); on Prop 13, e.g., which he initially opposed but then immediately accommodated himself to, it was more the latter (this is a better example of Brown’s own political cowardice). In the context of the post-McGovern and post-Watergate Democratic Party, this made Brown in the mid-1970s a model for one possible new direction for the party, though it was a new direction that was maddeningly difficult to define.

This was also Brown’s persona as late as his 1992 Presidential campaign, in which he ran on a platform that included both a living wage and a tax plan (designed by Arthur Laffer) that proposed replacing the progressive federal income tax with a flat tax plus a VAT.

It’s only in his most recent — and presumably last — political incarnation that he’s become a (slightly) more conventional Democratic politician.

Thanks for the reply and perspective. I’d forgotten about his ’92 campaign.

“Political cowardice” accounts for a lot of US policy. The template was laid down at least by the time of McCarthy, maybe earlier, I’m no scholar (or American) so that the accusation to avoid at all cost was being “soft on …” First soft on communism, but then you could pretty well fill in the blank with the fear being mongered at the moment. It’s why Congress so supinely gave Reagan all the funding he requested for El Salvador’s death squads. No one wanted to be labelled “soft on communism” even then.