My book orders for spring were due yesterday – not a problem for the surveys, since I am using The American Yawp. But it is a problem for my special topics course, designed for juniors and seniors in the history major. I’m teaching “The History of American Higher Education” – a subject in which I am purportedly (and actually) an expert. I did not turn in a book order. I will, though – soon!

But where to begin? How many monographs to assign? Which articles to assign? How to organize the course? What kind of research project to construct for the course? This is one of the most welcome problems I have ever had the opportunity to solve. I am nowhere near sorting it all out, but I do have some ideas, and I figured I would share them with you all. Constructive criticisms and further suggestions are most welcome.

Where to begin?

Where to begin?

I’ll begin wherever my students are. I want to know why they’re interested in the class, what they are studying, and why, and what they value in their own education and hope to achieve through it or do with it upon graduation. And I’ll ask them what they’d like to know / learn about higher education in America. After we’ve had that discussion, thenI’ll hand out the syllabus. My surmise is that most of their questions / concerns / interests will be in there somewhere, and I’ll tease those out in the intro course.

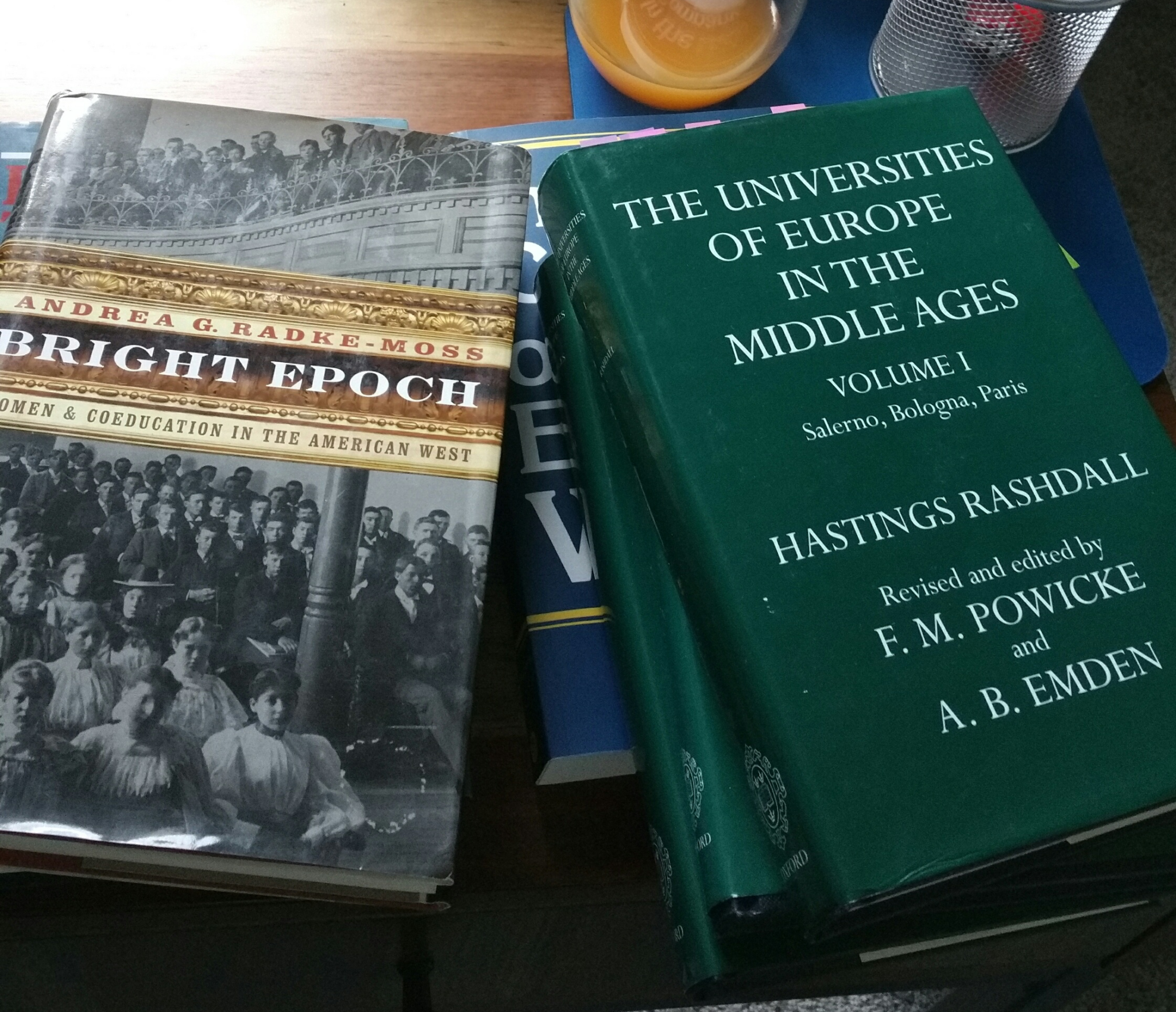

In terms of where I’ll begin the story on that first, important day, I’m going to start with the longue durée history of the university in the Western world. (Actually, I’m going to start a little before then, with Augustine and with monastic orders – just a quick sketch of book-learning and book-teaching prior to the establishment of the medieval universities.)

But where to begin on the syllabus?

I’ve decided to cover the whole institutional history of U.S. higher education from 1637 to circa 1828 in a couple of class sessions. No deep dives into the particular characteristics of each of the pre-Revolutionary institutions, but a nod to the theological controversies afflicting Harvard, Yale and Princeton (and mostly notafflicting, say, the University of Virginia). I’ll probably assign some Benjamin Rush, some Thomas Jefferson, some Francis Wayland, and the Yale Report of 1828 – no monograph on this long and important period, because one must make choices. I’ll make an overview/handout/”dudes and dates” document my students can keep and refer to throughout the semester.

On the monographs, here are four that I’d like to assign and discuss in class:

Andrea L. Turpin, A New Moral Vision: Gender, Religion, and the Changing Purposes of American Higher Education, 1837-1917(Cornell, 2016)

I have written about Turpin’s book before here at the blog. I think it does a magnificent job as a broad survey of major developments in American higher education (co-education at Oberlin, making a beginning of women’s-only institutions at Mt. Holyoke and later Bryn Mawr, the founding of land grant universities, the rise of the research university), while at the same time offering an outstanding model for how to do history of education as intellectual history. I can’t recommend this book enough.

Nathan M. Sorber, Land Grant Colleges and Popular Revolt: The Origins of the Morrill Act and the Reform of Higher Education(Cornell, 2018)

I’m counting on Cornell Press to come through here – projected publication date is Dec. 15, and the semester begins in mid-January (so yes, I will get the book order in soon). If there’s any delay in availability of this title, I may have to do a last-minute swap and assign some chapters from the excellent volume Sorber co-edited with Roger Geiger, The Land-Grant Colleges and the Reshaping of American Higher Education (Transaction, 2013). I will certainly be assigning Susan Richardson’s article, “’An Elephant in the Hands of the State’: Creating the Texas Land-Grant College,” since my students and I find ourselves (quite contentedly, in my case and I believe in theirs as well) at a college that, a couple of decades after its founding, became part of the Texas A&M system.

Stefan M. Bradley, Upending the Ivory Tower: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Ivy League(NYU Press, 2018)

I just got Bradley’s book in the mail earlier this week, so I haven’t cracked the cover yet. But I am excited to read how Bradley re-envisions and re-frames “the narrative” that seems to lie at the root of almost every recent and/or current culture war in higher education: the inclusion of Black students, Black scholarship, and Black perspectives and intellectual traditions in the classroom and the curriculum of American universities. We have all read plenty about the trauma of Cornell – the trauma for the white professoriate. This is often identified as a key moment in the rightward lurch of many a neoconservative (including Sidney Hook, who resented and resisted the label which nevertheless fit him perfectly). How wonderful, then, to be able to read a deeply-researched scholarly work that focuses not on the trauma for some resistant professors but the triumph for some powerful ideas and the ensuing transformation of the higher ed landscape.

Tressie McMillan Cottom, Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy(The New Press, 2017)

Though I can’t say for sure, I have a feeling that my students will enjoy this book immensely, for its style as well as its obvious and immediate relevance to their lives, the lives of their parents and siblings and cousins, and to their own anxieties about future work and college debt. Half of our students at Tarleton are first-generation college students. Over forty percent of our students are Pell-eligible. Over thirty-seven percent come from under-represented groups. They have landed at a reasonably affordable teaching-focused state land-grant university – and this book will help them understand all that is at stake in their choice to come here, and all the pressures to “economize,” to cut corners, to delimit from the outset their dreams for their own future. Those pressures do not come from within this university, but they are assailing it constantly, as education gives way to credentialism, and as the non-elite college students of America (and their loan debt) become a cash cow for privatizers and profiteers. I want my students to leave this class armed with the knowledge to contend for the value of publicly-funded, publicly-supported higher education for students who come from backgrounds just like theirs.

What else?

I probably shouldn’t assign more than one or two more monographs – two at the very most. Undergraduates in general have become acclimated to rather light reading loads, and I am also concerned about expense. (Note to professors: alwaysput an extra copy of your course textbooks on reserve at your university library. Most of us end up with multiple copies of books we use – and that’s a great use of those extras.)

So here are some topical possibilities for additional books; I’d welcome your suggestions:

The HBCUs

The GI Bill and its Effects

The Cold War and American Higher Ed

Women’s Higher Education in the United States

(NCAA) Athletics and Higher Education

Ideally, a book on the GI Bill, or a book on the Cold War, or a book on women’s higher ed or the rise of college sports in the U.S. would bring those general topics into conversation with Black history or Latinx history or immigration history. So if you know of a volume in any of these fields that does an outstanding job being, if not intersectional, then solidly cross-sectional, I’d very much appreciate a recommendation.

And if you have some favorite articles you assign in this field (or that were assigned to you), add them to the comments for the sake of all our readers.

15 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I wonder if there’s a way to make use of Craig Steven Wilder’s Ebony and Ivy, and some of the results of his work, and maybe even to find a way for your students to do some research on the history of their school and higher education in Texas?

I thought of Ebony and Ivy, but I think the Bradley book is going to be a better fit for my students’ situation and for our institution. And yes, they will absolutely be researching the history of desegregation at Tarleton, as well as the history of co-education. (This is Texas; co-education happened a lot earlier than desegregation.)

Tarleton’s institutional history is very peculiar and interesting, as land grants go. It was endowed by a benefactor in his will, and was founded as a private agricultural college. It is, I believe, the largest agricultural college (or at least the largest college with a working farm and farming majors) that was not founded as a land-grant institution. However, Tarleton has since joined the land grant system.

I cannot tell you how delightful it is for this woman from California’s bountiful San Joaquin Valley to teach at a school with a rodeo team, a “meat lab” where I can purchase steaks and roast and ground beef that students have processed from the university’s herd of beef cattle, and a view of wide open spaces and rolling farmland out my study window. It feels like home. I hope it can be.

While there are many more salacious on college athletics, I still think that Schulman and Bowen’s “Game of Life” is a great overview of the many pitfalls, from Division I to Division III.

Thanks for the recommendation. I checked it out and read six of the chapters I found likely to be of most interest. The book is dry and overly focused on presenting a quantitative picture of college athletes. To be sure some of the data are interesting but much of it is from the 1989 cohort and even the smaller amount from the ’99 cohort is now two decades out of date. Not recommended for teaching with unless there’s an updated version of which I am unaware, and even then I’d lift the best graphical data for a single class discussion only.

This sounds like a terrific class! I really appreciate your post and this well-chosen lineup, LD. Another idea: Use selections from the speeches given by African-American women who pioneered new thinking about education at the World’s Fair, 1893 (Anna Julia Cooper, Hallie Quinn Brown, Sarah Jane Woodson Early, Frances Barrier Williams, &c.). Their addresses are short and readily available online; I think I hyperlinked them in this USIH post of yore: https://s-usih.org/2017/02/a-womans-work-presidents-day-anew/.

This sounds like a great class! I’m jealous that you get to teach it. Another couple of ideas: Andrew Jewett’s *Science, Democracy, and the American University* (2014). I wouldn’t assign the whole thing, but its discussion of the American university in the Cold War is quite good.

Also, you could have your students read some insightful critiques of the American research university. To my mind, the best ever produced is Irving Babbitt’s *Literature and the American College* (1908). And how about Thorstein Veblen’s *The Higher Learning in America* (1918)?

Thanks to all for these great suggestions, and thanks to those who chimed in on Twitter. (Also, thanks to the unnamed benefactor who emailed me a syllabus — that was very generous.)

The chapter I am working on now is one that I might be able to assign. I don’t know if anybody assigns draft chapters to undergrads, but it wouldn’t bother me any, as long as they didn’t share it. Honestly, that’s probably the audience to keep in mind anyhow as I forge ahead.

If anyone else has further suggestions, holler at me here or elsewhere. (And you might really have to holler, depending on the ambient noise situation. Too many frat parties as an undergrad, I guess.)

David Labaree’s _A Perfect Mess: the Unlikely Ascendancy of American Higher Education_ (U Chicago, 2017) is the most readable (and shortest) account I know of for understanding the transition from the ragtag, independent private religious colleges of the 19th c. to the pre-preprofessional, and often publicly-funded, research university of the 20th and 21st (Labaree’s prose is much brisker and readable than Veysey, Hofstadter, Geiger, etc.) Ch. 1 is particularly good at explaining how the organization and funding for US colleges is historically divergent from European universities (i.e. our colleges have always much more detached from state sponsorship, for better and worse) and why US universities came to be so much more dominant on the global stage (b/c they have raised so much more money from private hands). 16 of the top 20 colleges in the world reside in the U.S. How is it possible that schools like Duke and Vanderbilt have grown bigger endowments than Cambridge Univ. and the Sorbonne, etc.? Ch. 7 is very sharp on America’s brief fling with governmental support for colleges during the Cold War. Labaree argues that public funding for “liberal” research (rather than “professional” / utilitarian research) happened only for a very brief window of U.S. history.

I found Labaree’s book incredibly sobering because its historical narrative challenges the declinist narrative about public colleges that undergirds my core political beliefs. That is to say, Labaree argues (fairly convincingly to my mind) that the state-sponsored support for the liberal arts at American colleges was a historical aberration that lasted mainly from 1950-1980 (what Louis Menand calls the “Golden Age of higher education”). I don’t hear this idea–that public financial support for the humanities was historically exceptional–disputed often enough by historians. Too often we point to an arbitrary date in the mid 20th century (say, 1950 or 1960) and note the decline in public funding between now and then. Basically, many of us point to the mid-century university as our political measuring stick–let’s restore public funding levels to where they were at in 1960! Labaree challenges our sense that these (high) levels of funding are historically “typical”: things looks a lot different if you are using 1800 or 1850 or 1900 as your measuring stick for what colleges can expect from state support.

This was a difficult story to hear if you believe, as I do, in the obvious social value of public funding for the humanities and for the research university. I would imagine that most readers of this blog support the notion of a greater investment in public universities, and recognize that government funding has declined over the past 50 years. This is certainly the case at my own alma-mater, UNC-Chapel Hill, and it has been documented by Chris Newfield and others for institutions like the Univ. of California system, UW-Madison, Univ. of Virginia, etc. And I continue to believe in the value of public funding for these institutions.

But is state-sponsored support for higher education the norm, historically? Labaree argues that it isn’t–that most American colleges, for most of the past two centuries, have had to undertake a constant mad scramble for cash from students and private donors to stay afloat financially. As much as I hate to say it, Labaree convinces me that the measures of austerity and utility that we currently live under (the neoliberal university and the like) are much more historically representative of the way colleges have operated over the past 200 years. The Cold War university that most of us admire or were trained in was an historical achievement for the common good (like the New Deal), but this brief period of public spiritedness is not, alas, very representative of the wider sweep of higher ed in American history.

I haven’t read it yet, but Charles Dorn’s recent book, _For the Common Good: A New History of America Higher Education_, would seem to provide a very diff. perspective from Labaree. I think this book would fit well with your larger goals for your students. I’d love to hear if anyone has read this one yet!

These two articles are slightly more sociological in orientation, and focus mainly on the last 30 years, but I could imagine using them in the early or final weeks of your class as ways to frame the course for your students–to help them historically understand their (pre-professional) identities and attitudes towards college / their chosen major:

“From the Liberal to the Practical Arts in American Colleges and Universities: Organizational Analysis and Curricular Change,” Steven Brint, Mark Riddle, Lori Turk-Bicakci, Charles S. Levy. _The Journal of Higher Education_, Vol. 76, No. 2 (Mar. – Apr., 2005), pp. 151-180

Who Studies the Arts and Sciences? Social Background and the Choice and Consequences of Undergraduate Field of Study. Kimberly A. Goyette and Ann L. Mullen. The Journal of Higher Education, Vol. 77, No. 3 (May – Jun., 2006), pp. 497-538

One book that I don’t see cited much, but that is quite smart, is David O. Levine’s _The American College and the Culture of Aspiration, 1915-1940. He argues (contra Veysey et. al) that the early 20th c. was a crucial period of change–that things continued to change even after the establishment of research universities like Johns Hopkins, Chicago, etc. He has great chapters on the rise of business as a major, the origins of “general education,” and rise of community colleges.

This short piece is by a literary scholar, but it is very smart on _why_ it is important to teach the history of higher education to our students today (more relevant to you than to your students:

Williams, Jeffrey J. “Teach the University” _Pedagogy_ 8:1 (2007): 25-42.

Feel free to PM me for .pdfs of the articles if that would prove helpful.

Patrick, thanks for the recs. I have been pondering the Labaree book. I bought it when it came out, and read a few reviews of it, but I have yet to crack the covers. In some ways I have no problem with his argument that broad public support for higher ed was the exception, not the rule — if by “broad public support” one means public funding. I think we have WWII and the Cold War to thank for that more than anything else, and it was an exceptional level of spending even (especially!) in humanities and social sciences. However, I think of public support for education more broadly — I’m Cremin-esque there. Was there ever a more lavish demonstration of public support for higher education than the Morrill Act(s)?

But Labaree arguing (correctly) that the heyday of the Cold War university was the exception, not the rule, for higher ed funding would not in any way prevent me from assigning the book to my class. Even if “history says” that generous public funding for higher education was an aberration, we’re not obliged to reconcile ourselves to some sort of “return to normal.” No need to accept the past as the norm for the present. I am glad Labaree offers a tonic for nostalgia though.

I have really been debating whether I need to assign a survey-type book or just take care of that via an intro lecture and handouts and then good intros to discussion as we make our way through the semester. (And the fact that I’m mulling this over shows that my book order is, yes, a week late now, but I have it on good authority that, while not ideal, this is Okay, and as long as I get it in “soon” it should be fine.)

Anyway, thanks for the thoughtful and thorough recs — sure, email me the .pdfs. I’d be glad — LDBurnett AT tarleton.edu.

L.D. – I’m impressed by your lack of desire for historical buttressing for present-day political arguments. I’m probably more of a sucker for historical precedent. “Declinist” arguments about public funding still seem pretty alive and well among the IH tribe – I think Andrew and Ray argued something pretty similar (public universities used to get taxpayer money and now they don’t) just other week on one of the episodes for their podcast.

Fwiw, if I had to choose just 1 survey text, I might go with Geiger’s _History of American Higher Education_ — it covers the full sweep and is admirably comprehensive and is beautifully sourced. It’s a little dry in its prose, though. The Labaree is definitely more of an “analytical” history — it has a very specific argument to make (even a little repetitive at times) and tilts towards a sociological perspective. It’s also much more of a synthesis than a work of archival history. But the prose is sharp, ironic, even funny at times. It’s one of the more “readable” texts on higher ed history that I’ve encountered.

Come on, now, Patrick — Andrew Hartman and Ray Haberski are just two dudes with a podcast. What do dudes talking to other dudes know about anything? But yes to the more general tendency of academics to look back on some “golden age” to which the present cannot compare and represents decline. Higher ed declensionism is a genre unto itself, and one to which I have probably contributed to.

But yes to the more general tendency of academics to look back on some “golden age” to which the present cannot compare and represents decline. Higher ed declensionism is a genre unto itself, and one to which I have probably contributed to.

I have Geiger (like, all of his monographs), and I like what he’s done with the most recent one, which seems clearly designed to serve as a survey text for a “history of higher ed” type course. If it’s out in paperback now, I might go ahead and go with it. I’m concerned at this point about monograph fatigue among my students, and also expense. I know for sure I’m going to add Stephanie Evans’s Black Women in the Ivory Tower, so that makes five monographs. I suppose if I salted Geiger through the whole semester I could get away with six. But I need to make sure that our library here has a copy of every monograph and then put it on reserve for my students, because book expenses are a real burden/barrier for our students here (and elsewhere, I’m sure).

Thank you for the .pdfs. Much appreciated.

How about teaching Chapter 3 (The Cold War University) of Jeremi Suri’s book Henry Kissinger and the American Century? I found it to be a very insightful, and written for a general audience that would include juniors and seniors. It adds to the interest to see how one prominent individual used the mid-century university, and the connections it made possible, to great advantage.

Senator Ben Sasse, former college president, said in this weekend’s New York Times Sunday Book Review that he has “The Innovative University: Changing the DNA of Higher Education From the Inside Out,” by Clayton Christensen on his night stand. I don’t know anything about it, but Sasse is a generally thoughtful guy, so it might be worth a look. Here’s the link to the By the Book column with his other reading recommendations: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/21/books/review/ben-sasse-by-the-book.html?emc=edit_bk_20181121&nl=book-review&nl_art=&nlid=11537660edit_bk_20181121&ref=headline&te=1

Not a text for undergrads, but useful for understanding the institutional ‘framing’ of critical practice in the academy nonetheless, I would recommend the first chapter, Literary Criticism and the American University, of Jonathan Culler’s 1988 Framing the Sign. It covers the period 1920-1980, focusing heavily on the New Criticism and the later rise of Theory.

My apologies for the multiple comments to this thread. I just happen to have been reading quite a few disparate texts that speak to this subject as of late.