By 1968 John Wayne was as politically polarizing a figure as he would probably ever be. In June of that year, he released his Vietnam movie, The Green Berets. He was a vocal supporter of the war, and the film had been made with the full cooperation of the Department of Defense. It presented the US mission in Vietnam as a stand for freedom and justice and blamed America’s difficulties there on a sapping of nerve perpetrated by an unpatriotic press corps. That message might have played less divisively a year earlier, before the Tet Offensive, before Lyndon Johnson’s announcement he would not run again. Screenings drew antiwar protests; reviewers pilloried the film. “The Green Berets became the focus of a divided America,” writes J. Hoberman in The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties. “LBJ’s abdication left Wayne the lone authority figure standing.”

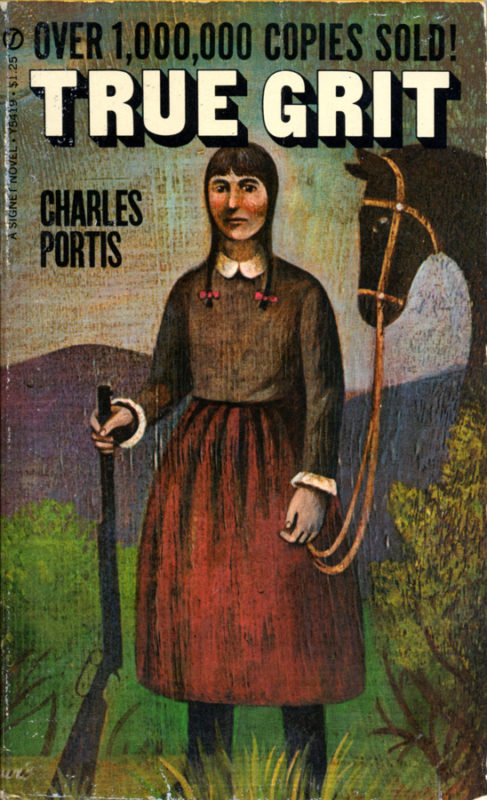

Nineteen sixty-eight was also the year Charles Portis’s novel, True Grit

, was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post and then released in book form. A movie version came out the following year, starring John Wayne in the role of Rooster Cogburn. As Rooster, Wayne projected no less self-regard than he had as the super-competent, fighting Marine Colonel he’d played in The Green Berets. In other ways, however, Wayne in the Rooster Cogburn role was somewhat reduced: fat, drunk, and with an eye-patch. Wayne embraced the role, was embraced in it, and it came to represent the last phase of his career.

One can’t talk about True Grit in its times without talking about John Wayne, but it’s in the manner of clearing brush from the path. Wayne’s cultural and professional stature shaped the film, focused the story on himself, and thus shaped the way people understood it, especially if they never got around to reading the book. So we need to move Wayne and the film out of the way. True Grit the novel isn’t Rooster Cogburn’s story. It belongs to its narrator, Mattie Ross.

“I was just fourteen years old,” goes the novel’s second sentence, “when a coward going by the name of Tom Chaney shot my father down in the street in Fort Smith, Arkansas and robbed him of his life and his horse and $150 in cash money plus two California gold pieces that he carried in his trouser band.” The year is never named, but a history buff with basic math skills can figure it out—1878. Fifty years have passed since the murder, Hoover has been elected president, and a fully grown Mattie is looking back on how, at fourteen, she hired a U.S. marshal (Rooster) to track the killer into Indian territory, to catch him and exact her revenge. Her supreme confidence in the righteousness of her cause burns even brighter than does Wayne’s and his cohort for the cause in Vietnam. Mattie’s mission, too, is one of justice in the territory, as it were, in the wild.

“I was just fourteen years old,” goes the novel’s second sentence, “when a coward going by the name of Tom Chaney shot my father down in the street in Fort Smith, Arkansas and robbed him of his life and his horse and $150 in cash money plus two California gold pieces that he carried in his trouser band.” The year is never named, but a history buff with basic math skills can figure it out—1878. Fifty years have passed since the murder, Hoover has been elected president, and a fully grown Mattie is looking back on how, at fourteen, she hired a U.S. marshal (Rooster) to track the killer into Indian territory, to catch him and exact her revenge. Her supreme confidence in the righteousness of her cause burns even brighter than does Wayne’s and his cohort for the cause in Vietnam. Mattie’s mission, too, is one of justice in the territory, as it were, in the wild.

It may seem absurd to read True Grit as a Vietnam novel. Certainly none of the reviewers blurbed on my copy of the 1969 paperback made that association. They didn’t see the book as divisive, in the way so many events and other cultural items of the period, such as The Green Berets, were divisive. On the contrary, True Grit “should be enjoyed by people of all ages” said the Cleveland Plain Dealer; it was a pleasure “regardless of age, sex, class, color or country of origin” (Newsday); it spoke “to every American who can read” (The Washington Post). If Vietnam and everything else was dividing Americans, here was a book that could bring them together. That commentary itself is a commentary on the times.

Even so, if we broaden the focus a little, we can find a more significant connection in the book’s themes. Explanations for the Vietnam War and other of the United States’ brutal foreign adventures are typically found in a complex of ideas—religious, philosophical, political, economic. According to these ideas, not only providence but a certain economic ruthlessness entitle America to assert its will. So it is with Mattie Ross, with her cause and with her character. In this way, True Grit can be credibly read as a critique of American Exceptionalism at the very time when American Exceptionalism was under a bright lamp of interrogation.

A friend once read the novel on my recommendation and half-dismissed it as mere fable. He couldn’t get past the fact that a fourteen-year-old girl would be permitted along on the hunt. “That would never happen,” he said. But to reject this plot point is to underappreciate who Matte is. She bullies Rooster into taking her with him, just as she bullies everyone who gets in her way. A good deal of the book’s humor comes from the fact that Mattie doesn’t realize what an insufferable hard-ass she is. Rather, she sees her way as the way of things, which she constantly justifies, sometimes with platitudes of the Protestant work ethic, sometimes outright with verses of scripture, but mostly with the logic of the market.

“When I have bought and paid for something I will have my way,” Mattie tells Rooster. “Why do you think I am paying you if not to have my way?”

The authority of money and the authority of scripture: Max Weber made that connection a long time ago in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. For a more contemporary take, I read William E. Connolly’s 2010 essay, “The Evangelical-Capitalist Resonance Machine.” There Connolly describes a self-perpetuating “assemblage” of “cowboy marketeers” and Left Behind series enthusiasts. What energizes this assemblage, he wants to know, what makes it so angry and so drawn to retributional violence? Connolly attributes these characteristics to the displaced venting of existential resentment. One side resents the future, that it requires a check on present-day greed; the other side resents those whose alternative faiths saddle their own with uncertainty. These anxieties reverberate, their “electrical charges resonate back and forth,” so that

its participants identify similar targets of hatred and marginalization, such as gay marriage, women who seek equal status in work, family and business; secularists, atheists, devotees of Islamic faith, and African American residents of the inner city who do not appreciate the abstract beauty of cowboy capitalism.

Evidence of what Connolly was talking about can be found in our current president’s obsession with strength and his eagerness to express it through cruelty. A certain segment of the population was looking for someone to deal with immigrants, uppity women and people of color as John Wayne would a desperado in the territory. They were looking, as Mattie was, for someone with grit, so as not to dilute with mercy the righteousness of their revenge.

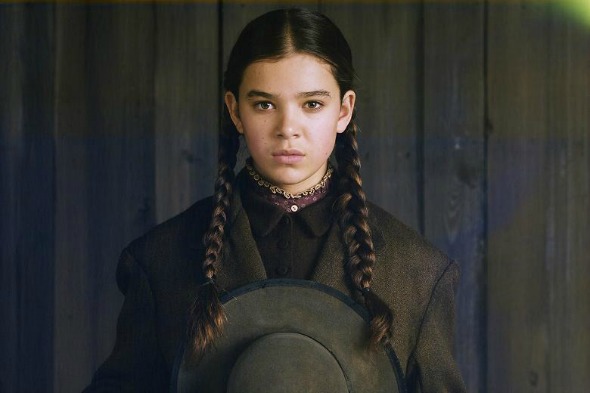

Hailee Steinfeld as Mattie Ross in the 2010 film version of True Grit.

But these are harsh readings of Portis’s novel and probably not the best ones. They fit better other fictional characters we’ve come to know: Captain Ahab, Noah Cross, Mr. Potter, Daniel Plainview. We despise these characters, and rightly so. In contrast, Mattie Ross has our sympathy and even our affection. The “I will have my way” line quoted above comes during a contentious argument over whether she and Rooster will join forces with the Texas Ranger who is also tracking Tom Chaney for another crime, and whether Chaney will be taken alive. Mattie is adamant, insisting on exactly the revenge that she’s paying for. “You are young,” Rooster tells her. “It is time you learned you cannot have your way in every little particular. Other people have got their interests.” Mattie reports this dialogue but pays it no heed. The reader chuckles. Rooster’s assessment is very accurate, indeed.

Both film versions of True Grit have much to recommend them. Neither do justice to the book. Neither find it possible to dramatize Portis’s heart-breaking handful of final paragraphs. This is where the reader grasps the true price Mattie paid for her revenge, and that it was bigger than the one she reckoned. Now in her sixties, she’s a rich and powerful business woman, a personage in her community, with a finger in many pies. She’s also bitter and loveless, a character people fear but make fun of behind her back.

They say I love nothing but money and the Presbyterian Church and that is why I never married. They think everybody is dying to get married. It is true that I love my church and my bank. What is wrong with that?

To answer Mattie’s question, nothing is wrong with that, not on the face of it. But again, in these final paragraphs, Mattie reveals something she doesn’t herself see. She never learned what she needed to learn about other people’s interests, and that makes Portis’s great comic novel a great American tragedy.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I cannot comment on the book (which I haven’t read), but I’d like to offer an alternative take on the original film version, which, if memory serves correctly, I first saw at a drive-in theater with my family in 1969 (when I was 15 years old). The film was considered to be a special kind of John Wayne vehicle, in which the viewing audience was beginning to say farewell to a personification of the nation’s (imagined or idealized) frontier heritage. I recall the headline of a review of True Grit was something like: “A Hilarious Climax to a Living Legend.” Wayne was about 62 when he shot the film, and he was playing a flawed, over-the-hill (but still effective) version of his more heroic earlier Western roles. His character, Rooster Cogburn, was said to have “true grit,” which roughly meant toughness and fortitude (he wasn’t the best tracker or best shot among bounty hunters, but he was the most determined). Off screen, the actor John Wayne may have been a buffoonish reactionary; but on screen the characters he played in Westerns and war films were steady, tough, and reliable. In short, Wayne the movie star embodied the characteristics most admired by men (and for men) of the “Greatest Generation.” In watching Wayne’s late-career portrayal of a one-last-time rough-and-ready strongman, filmgoers could both celebrate and note the passing of an older set of values, which were in the process of being replaced (in the eyes of younger Americans) with alternatively preferred character traits in the year of Woodstock.

When I was a teenager in the late-60s and early-70s, me and my male friends would often discuss how our fathers were always telling us (directly or by implication) about how much tougher they were (compared to us) when they were our age. And they were right. But if you grew up in a scrappy urban neighborhood during the Great Depression and then went off to fight World War II, you had to be tough. Toughness and fortitude were admired because they aided survival and success. By contrast, toughness was not the primary characteristic required or admired among the cohort of affluent, secure, spoiled, college-bound, suburban baby boomers, to which me and my friends belonged. Traits such as sophistication (real or imagined), coolness, a sense of irony, humor, intellectual self-confidence (over-confidence was the norm), constructive irreverence, and identification with anti-heroes were more useful in our circumstances. To use the language of that era, John Wayne could still be (nostalgically) appreciated, but he was no longer relevant.

Great comment. Yes, toughness and fortitude are the components of the grit at question in both film and book. Although he was too young to be part of the greatest generation, my father liked John Wayne movies for exactly the reasons you state. I don’t disagree with this alternative take … though I don’t think the reactionary bufoonery was kept altogether out of his films, especially those later ones. A case might be made for irony as a kind of necessary psychological toughness, too.

Note: I’ve straightened out an error as to the novel’s timeline since this piece was originally posted.